In late 1999, the United States Army found itself confronted with a severe recruiting shortfall. Despite the Army’s best efforts, it fell just over 6,000 recruits shy of its goal, setting off alarm bells within the organization. Within the upper ranks of the Army, a ‘doom and gloom’ PowerPoint presentation began circulating, one that laid out in stark terms both the demographic challenges recruiters were facing, and the difficulties of convincing young Americans that a career as a soldier might be for them.

Amidst all the statistics, bar charts and graphs in the presentation, one slide stood out to me. The presentation closed somewhat melodramatically with a quote attributed to Sulla, speaking ‘after the Romans completed their conquest of the known world’ in 84 BC: ‘now the universe offers us no more enemies, what may be the fate of the Republic?’

This comparison of the United States to the ultimately ill-fated Roman Republic was just one piece of evidence among many that highlighted just how uncertain many within the Army were about their place in the world after the end of the Cold War. I became interested in writing this book after I had noticed similar themes cropping up in the pages of the Army’s professional journals, those outlets where soldiers talked to each other about their profession and its future. Again and again, they told each other that the warm afterglow of the Cold War’s end would not last, and many expressed unease about what was to come.

It was surprising to me to see that an organization that was unmatched in its military power, one that had recently vanquished the Iraqi Army in an overwhelmingly lopsided Persian Gulf War, could be so troubled about its future. Even as the United States stood alone as the last remaining superpower in the 1990s, its soldiers were uncertain and anxious about what might come next.

Uncertain Warriors tells the story of how that uncertainty manifested itself, and what Army leaders did to try to resolve it. Fundamentally, the questions they had about their role and purpose in this new world boiled down to this central question: what was an army for at the supposed ‘end of history’?

These questions were not just posed by Army leaders. The American public simultaneously lauded its military for its triumph in Operation Desert Storm and held its armed forces in extraordinarily high regard, and asked why it was so out of step with evolving societal norms on gender and sexuality. Within the Army’s ranks, many of its soldiers asked the same thing, and the institution spent much of the decade roiled by debates over whether more roles should be opened up to women and whether openly gay personnel could serve at all.

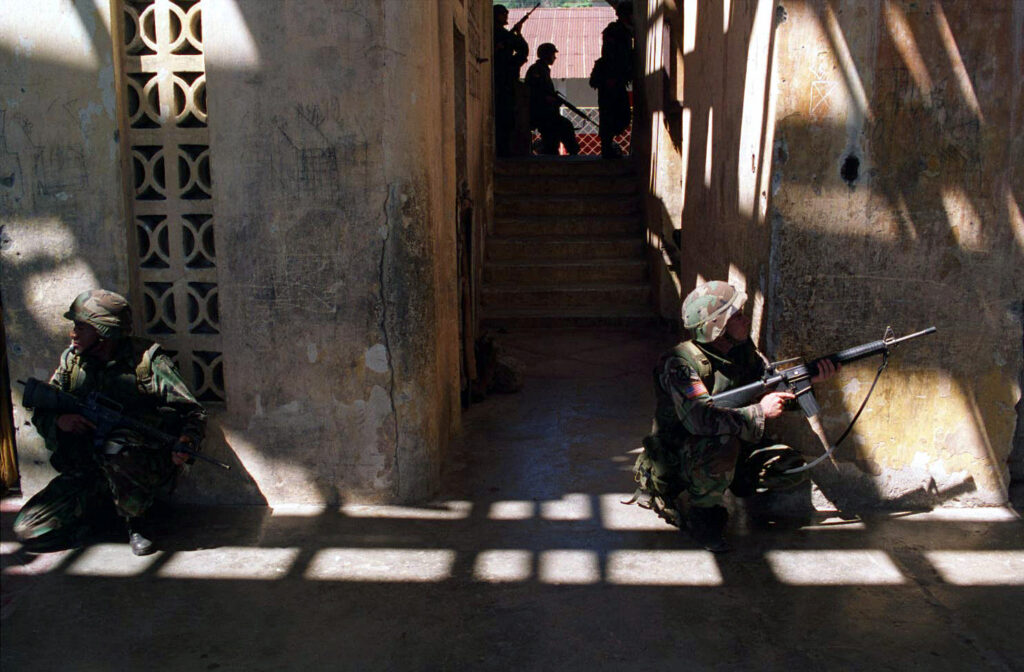

The Army, the political class, and the broader public also found themselves wrestling with the challenges of peacekeeping operations, a seemingly new mission for the Army that required it both to embrace unfamiliar tasks such as mediation and civil-military cooperation and to emphasize much older soldier skills such as patrolling on foot and running checkpoints. This reluctant turn towards peacekeeping took place at the very same time as many within the Army sought to embrace a putative ‘revolution in military affairs’, and the military as a whole poured huge resources into research and development in the hopes of producing a revolutionary ‘leap ahead’ in technology that would allow the U.S. military to keep its predominance in conventional warfare for decades to come.

All these issues, and more, combined to drag the Army in different directions. Ultimately, all those who contributed to these debates seemed to be arguing over the fundamental question of who and what the American soldier was supposed to be. Should they be a violent war fighter or an armed humanitarian? A citizen soldier or a professional warrior?

My book explores these dilemmas and shows how Army leaders eventually attempted to solve them by promulgating a ‘warrior ethos’ in the force. This vague but loaded term would apply to all soldiers, who would be taught to see themselves as warriors that were psychologically committed to the demands of combat, regardless of their distance from the battlefield. Army leaders hoped that this warrior identity could apply to soldiers of all genders and specialities, and that it would remind both civilian politicians and soldiers deployed on peacekeeping or humanitarian missions that the Army’s ultimate purpose was war.

Army leaders made a sustained effort to directly embed this ‘warrior ethos’ within the organization’s identity, making it a central part of recruiting and training at all levels, while also affirming that close combat was both a fundamental task for all soldiers and the core undertaking that differentiated them from the rest of society. It may seem strange than an era that had begun with claims about the end of history ended with the Army invoking such a primordial term and telling its cooks and clerks that they, too, were warriors, but the sometimes existential anxieties unleashed by the Cold War’s end could produce unexpected results and new ways to think about both the Army’s identity and its purpose.

Latest Comments

Have your say!