“Not as bad as we might have feared; not as good as we might have hoped” is one way to think of the four years in which Donald Trump put his uniquely Trumpian spin on US-Korean relations.

And lest we forget, there was reason to be afraid as President Trump taunted the young leader of a notoriously prickly regime, calling him “short,” “fat,” “rocketman,” “little rocketman,” and a “madman” among other names. To the name calling, Trump added threats of “fire and fury”, bragged openly about the size and potency of his “nuclear button,” and warned “military options are in place, locked and loaded.” North Korea responded in kind, threatening “a merciless blow at the heart of the US with our powerful nuclear hammer, honed and hardened over time.” Given the above, it’s hardly surprising that on 13 January 2018 citizens of Hawai’i crashed their wireless networks calling their loved ones to say a final goodbye when their state’s emergency alert system erroneously warned of an incoming ballistic missile.

If President Trump’s verbal fusillades at Kim Jong-un caught the attention of the general public, it was his attacks on South Korea—an American ally—that made seasoned observers of US-Korean relations wince. Trump slapped tariffs on key South Korean products, including steel, while castigating South Korea for “free riding” on American security—a claim that was as insulting as it was inaccurate. He also mused openly about withdrawing US forces from the Korean peninsula if Seoul did not pay up. Those familiar with the outburst of anti-Americanism that plagued US-Korean relations in the early 2000s, including myself, braced for images of American flags being torn to shreds on the grounds of City Hall in Seoul.

And yet, there were also reasons to hope.

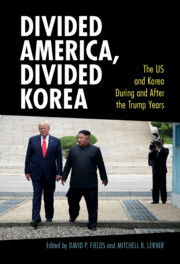

Few informed individuals believed that Trump’s abrupt change of strategy with Kim Jong-un—from open hostility to “bromance,” resulting in three historic face-to-face meetings—would result in a breakthrough, but there was always a chance that it could. If it did, who could deny that he should be nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize? US Presidents have been awarded it for less. Besides, since nothing else the US has tried towards North Korea has been successful, why not try something quite different?

South Korea’s response to Trump was also a source for hope in a way. While the South Korean leadership firmly refused President Trump’s demand for a five-fold increase in its contribution to the alliance’s costs, there were no diatribes, no popular outbursts of anti-Americanism, and neither Psy—nor any other Korean pop star—called for violence against Americans, as he had done twenty years ago. There was hope that South Korea, now a mature and confident democracy, could simply brush off Trump, and his insults, as a passing moment of populism in an otherwise stable alliance relationship.

In fact, despite all the headline grabbing developments, it would be difficult to argue that US-Korea relations in January 2021 looked much different from January 2017. North Korea was still as menacing and bellicose as ever. Its nuclear ambitions remained unchecked. Its people still suffer the lowest standard of living of any in East Asia. South Korea was still an American ally. Camp Humphreys was still hosting more than 20,000 US soldiers. In spring 2021 the US and South Korea so smoothly negotiated a new cost sharing agreement that it seemed the Trump demands that threatened the alliance might just have been a bad dream.

But the Trump years were not a bad dream and, while subtle, their impact on US-Korean relations could be profound. The essays in Divided America, Divided Korea explore some of these impacts, especially South Koreans’ loss of confidence in the alliance, their newly popular interest in having their own nuclear weapons program, and their growing fears that this alliance—rather than protecting their security—might unwittingly suck them into a conflict with China. Essays on North Korea examine how the Trump Administration failed to do the sort of basic legwork on North Korean human rights abuses that, while rarely offering amelioration to the North Korean people, do maintain steady pressure on the regime. Essays that broaden the scope regionally to include China and Japan show a similarly worrying story of Trump provoking friends and competitors alike.

All the essays in this volume agree that the Trump Administration failed to fundamentally change US-relations with the Korean peninsula in the short term—mostly because Trump and his team were dysfunctional and ineffective, but also because the inertia of existing relationships was too strong. North Korea could not be converted into a friend nor South Korea into a competitor in just four years.

Where these essays identify long-term impacts of the Trump years, they are clearly negative. The deterioration of US-China relations (for which Trump is more responsible than most) and the War in Ukraine (for which he is not) have broken the six-party coalition that used to present a mostly united front against further North Korean weapons development. As a result, North Korea is enjoying a more permissive international environment for its antics than it has known in decades. A similarly negative trend is apparent in US-South Korean relations. Yes, the relationship survived Trump and in some ways appears to have come back even stronger with trilateral security cooperation between the US, South Korea, and Japan perhaps better than at any point in its history. But this new health should not mask the true state of the alliance, in which Korean anxieties over the credibility of American security guarantees and the commitment of the United States to liberal trade policies has Seoul bracing for a second Trump term. To quote Bono, the US-South Korean alliance is “not broke, but you can see the cracks”—cracks that a Trump Administration 2.0 is going to hammer on if it gets a chance. Whether or not it is given that chance will have a profound effect on US-Korea relations and the future of East Asia in general.

Divided America, Divided Korea

edited by David P. Fields and Mitchell B. Lerner

Latest Comments

Have your say!