Literate white men of European descent were the most common readers in the past. At least that seems to be the case if we look at the history of books and reading. Indeed, these men wrote, published, and read plenty of books, as a large body of scholarship has shown for Europe – the cradle of book history. Erudite men living in colonial places around the world participated in this book culture, too, but not only them. If we trace the itinerary of printed wares and books from the cultural and material contexts to the recipients and, by doing so, focus on the reach of reading material a different, more colourful history of book users emerges.

In the Viceroyalty of Peru in South America – a region with strong social hierarchies and not really famous for its book culture – reading material could frequently be found displayed in the cities’ shops and stalls in the decades before Independence between ca. 1760 and 1824. Though colonial legislation did not allow for a free production and trade in books, literacy was increasing but still low, and most printing supplies had to be imported from Europe, books were a common commodity. Bringing together the printing activities in colonial Lima and the Spanish import trade, an unprecedented scale of books was for offer on the marketplace. All different genres from scholarly volumes to ephemeral prints, from devotional prayer booklets to how-to manuals, and from the almanac to primers could be found in the stocks of traders. There was no separate category of ‘popular books’ but printed commodities of all sort and subject mingled in the displays, often next to other everyday victuals.

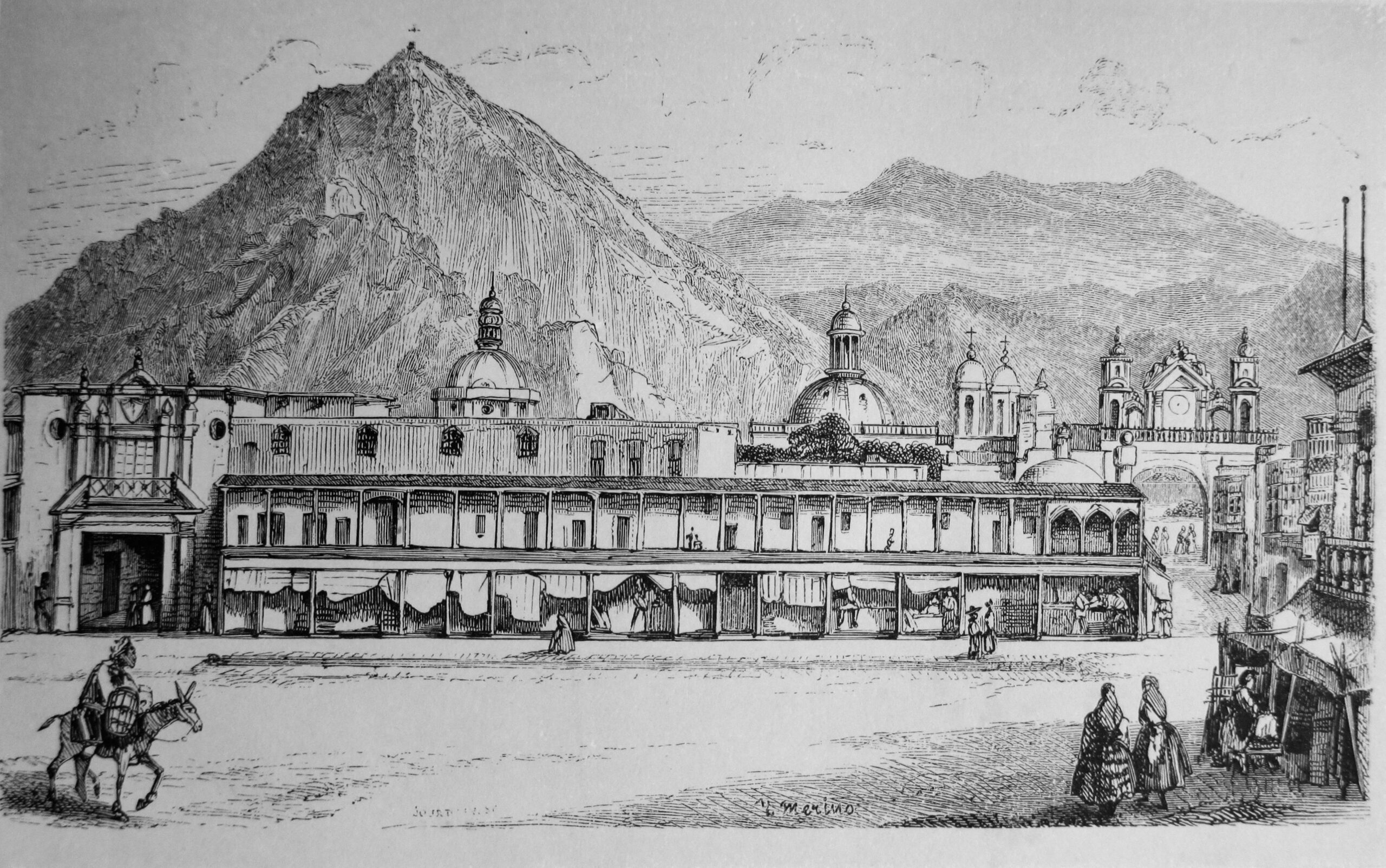

The printing technique and books existed since the early days of the Viceroyalty. At the end of the eighteenth century and beginnings of the nineteenth, Lima with its longstanding typographic tradition and as the centre of power was the ‘lettered city’ par excellence. Not only did the Peruvian capital host a handful of printing workshops, it also formed a hub on the South American continent for the distribution of reading material, even such of prohibited content. Moreover, there was a large offer of used books for sale, especially in cities, which made access to books relatively easy. By following the books as objects to different sites in the Viceroyalty, we encounter them as items on custom bills. Muleteers brought books to the nuns in Arequipa, and jurists packed volumes of their faculty on the journey from Lima to Cuzco.

Books formed part of the possession of women and men throughout the Viceroyalty. At the end of the eighteenth century, different ways of informal education and popular practices of reception broadened the group of those potentially interested in books. Studying books as items in inventories, the group of book owners in late colonial Peru included persons of all social backgrounds, for instance, an Indian cacica, a barber of African descent, and a Spanish artisan alike. Even illiterate persons, who could not sign their testament because they did not know how, listed books in their belongings and we can only speculate whether it was for economic or symbolic value. While print did not yet penetrate all spheres, it made up a considerable and growing part of everyday life for many in late colonial cities. The social practices around printed commodities point to various uses and diverse interaction with texts, including the lending of books, learning the alphabet, and reading aloud.

Aligning Peru with broader trends in the Americas and Europe, the increased printing and reading characterised a self-reflexive era that labelled itself the Enlightenment – in Spanish: La Ilustración. The new and growing participation in print culture in late colonial Peru proves the book’s role in the urban society in addition to the extended user group of reading material in this new age of Enlightenment. It was not only erudite men who possessed books, but ordinary people frequently used reading material as well. Against the backdrop of research in global book history, A Colonial Book Market provides a social history of books situated in the specific context of the Spanish Empire and marked by transatlantic connections.

Latest Comments

Have your say!