If you have been following the news in the past months, you may have read that Democrats in the United States reported that the White House under Donald Trump failed to report gifts received by the former president from foreign nations. Moreover, other gifts went missing. Similar stories have also made the news in Brazil. Former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and first lady Michelle Bolsonaro received exquisite jewelry and watches as gifts from the government of Saudi Arabia, and then illegally sold several of these expensive items. That chiefs of state receive gifts from foreign nations is nothing new. For example, the collections of John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum feature dozens of artworks and artifacts offered to him by African chiefs of state.

Exchanging gifts is also part of the protocol of the end of the year’s holiday season in Europe and the Americas. But beyond twentieth century diplomacy, the expression of affection and today’s avid consumerism, exchanging gifts has been part of social protocols since at least antiquity. Gifts have been central instruments in diplomatic exchanges throughout the Middle Ages and during the early modern era, therefore helping to seal agreements and start business dealings.

What few people know is that during the era of the Atlantic slave trade, upon their arrival on African shores, European and American slave traders also offered gifts to African rulers and brokers, before starting the process of purchasing enslaved Africans to transport them to the Americas.

Most of the the time, gifts were exactly the same items carried on board of slave ships to the coasts of Africa, where they were employed as currencies to purchase enslaved people. Among these items were textiles, alcohol, cowries, and iron bars. In this context, these articles were tributes of sorts, given to the various African agents established along the coast to initiate the trade.

Over the years, European traders learned the very specific tastes of African rulers and agents, and therefore provided particular items to specific African traders to please them and in exchange obtain the best captive Africans within the minimum period of time. In this context, gifts could also be conceived as bribes, as by offering them to African agents, European ship captains and traders sought to get advantageous conditions in the trade of human beings. For example, expensive textiles, and manufactured articles such as clothes, hats, and metalware were reserved to rulers and agents occupying higher offices. Moreover, as part of these exchanges, African traders also offered men, women, and especially children as gifts to European traders and rulers.

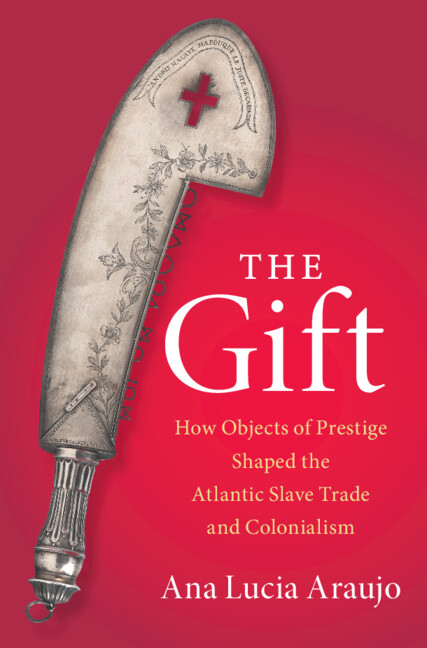

Gifts of prestige made of valued materials remained essential items in the Atlantic trade of enslaved Africans until the middle of the nineteenth century. But like the presents given to Trump and Bolsonaro, there are controversial stories behind some of these gifts, today housed in European and American museums. My book The Gift: How Objects of Prestige Shaped the Atlantic Slave Trade and Colonialism draws on one of these stories to explain the importance of luxurious gifts in the era of the Atlantic slave trade. In the context of the Atlantic slave trade, gifts were also lost and stolen.

In June 1775, the French slave ship Le Montyon, followed by the corvette L’Hirondelle sailed from the French port of La Rochelle to the Loango coast in West Central Africa, to trade in the port of Cabinda and Malembo, in today’s Angola. Daniel Garesché, a very rich shipowner, slave trader, and future mayor of La Rochelle, then France’s second busiest slave-trade port, outfitted and owned the two vessels.

After arriving in Cabinda, a port controlled by the Kingdom of Ngoyo, French traders from Bordeaux and Le Havre attacked the captain and the crew of the two La Rochelle slave ships and stole part of their cargo. Fortunately for them, the man who served as the commercial agent (mfuka) of the king of Ngoyo offered them shelter.

Two years after this incident, Garesché sent again a new vessel from La Rochelle to the Loango coast. This time the captain of his ship Le Montyon carried a ceremonial silver sword to be offered as a present to the Cabinda’s commercial agent. The gift was a way of telling him thanks for protecting the La Rochelle’s captain and crewmembers two years earlier.

At the end of the nineteenth century, more than one century after the French slave traders offered this precious gift to the Cabinda’s agent, French officers looted the sword not from Cabinda, but from Abomey, the capital of the West African Kingdom of Dahomey, located almost 2,000 miles away.

My book follows this silver gift from La Rochelle to Cabinda, and from Cabinda to Abomey, in the Bight of Benin. I explore how and why the silver sword was created, and by whom, and why it mattered for French traders and African local agents. I also examine the cultural, religious, and artistic meanings of this sword for the rulers and artisans of Dahomey, from where it was looted during the second Franco-Dahomean war in 1892. I argue that the silver sword provides a complex and nuanced framework to better understand the history of the Atlantic slave trade on the Loango coast, where the Kingdom of Ngoyo and Cabinda were located, as well as in the French slave-trading ports such as La Rochelle.

Ultimately, The Gift underscores the importance of material culture and also sheds light on the significance of gift exchanges and objects of prestige during the era of the Atlantic slave trade. The movement of this silver item also illuminates the connections between the Loango coast and the Bight of Benin, two regions that are usually studied separately by slavery scholars. The book also examines the complex trajectory of this silver sword and puts it in dialogue with other similar objects fabricated in Europe and Africa. By doing so, The Gift also contributes to complicating discussions about the looting and circulation of African objects and the demands of repatriation of African cultural heritage to European and American museums.

Latest Comments

Have your say!