In recent years, the pandemic brought into relief the tensions that arise from the many and varied ways that people make sense of the natural world and its relationship to bodies.

Masking. Vaccination. Social-distancing. Such public-health measures advocated by government agencies and the World Health Organization all met with flurries of alternative theories about the spread and impact of COVID-19. Appeals to the scientific consensus that formed as the disease made itself known could not dislodge the tightly held ideas assembled by COVID-19 denialists and the anti-masking and anti-vaccination movements. These were understandings of health and disease that emerged in the context of rhetoric, unrelenting enquiry on the internet (“do your own research”) and – sometimes – personal experiences of the failings of western biomedicine or government agencies. The truth of scientific consensus contended with a cat’s cradle of motivations that ranged from the fanciful to the nefarious.

Locked down in Melbourne, Australia, and completing a book about the discredited science of phrenology, I felt the tug of history as charismatic figures rose from the morass of dissent to build new careers based on homespun ideas. I watched the rhetoric of persecution used as obviously as it had been by popular lecturers during the nineteenth century when defending their theories from attack and building auras of saintly righteousness. And I reflected on a healthcare terrain that in former times had been plural and serviced by an array of healthcare practitioners, with university-trained doctors just one modality, and not always the most effective one.

In short, I watched and lived science defined by the language, mores and political tensions of the times and places that contained it. And the parallels with my own research seemed striking.

Phrenology heads south

The science of phrenology posited that character and intellect could be read from the shape of a person’s head. Developed at the end of the eighteenth century by Viennese physician Franz Jozef Gall, its adherents believed that, because the skull hardened around the brain during development, external reading of the head could provide direct access to the matter within. What’s more, because different parts of the brain performed different functions (a phenomenon known as “cerebral localisation”), a person’s finer, innate attributes of motivation, behaviour and aptitude revealed themselves through such analysis.

Of course, the phrenological map of ‘organs’ that denoted everything from godliness to intemperance to attraction to the opposite sex does not align with contemporary understandings of brain function. But thanks to the intuitive simplicity of its underlying concepts, the system could slip from the grasp of leading doctors and anatomists and into the hands of anybody with an interest in human nature and a pocket guide to assist them in learning the system.

Phrenology arrived in the Antipodes with European savants and the broad wash of migrants, and by the second half of the nineteenth century featured as a common entertainment that could be consumed everywhere from mechanics’ institutes to markets. Some phrenologists pursued a lifelong career. Others dabbled for a night or a short spell to scrounge a living, switching between popular science and other forms of labour. Contested from the outset, phrenology enjoyed an enduring life.

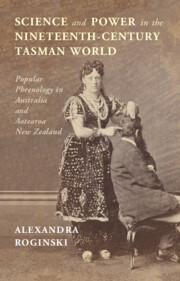

I traced the lives of more than 200 popular phrenologists to the extent that the archives allowed. Some brandished their skills in hundreds of newspaper articles and advertisements and fistfuls of pamphlets (Joseph Fraser, whose flyer features here, is among them). Others surfaced for a moment – in a passing mention in a book, or in police records, when the word “phrenologist” cloaks an existence of vagrancy or petty crime. Few really hit the big time, although Madame Sibly, who poses on the cover of my book, retired in ease on a property in rural New South Wales.

Most phrenologists shifted with the booms and busts of a region pockmarked by gold rushes, economic depressions and febrile new cities. Australia and Aotearoa are two distinct countries now, but following European invasion masses of people travelled and sailed between the colonies on either side of the Tasman Sea in search of riches, or even just base survival. Historians often refer to this emerging region of great mobility as the ‘Tasman World’. Here was a vast stage on which popular lecturers put their science into practice, lecturing in raucous displays, reading the heads of children for worried parents, and advising clients on their own mental ecosystem.

Science for the taking

A recurring question: Why did phrenology survive for so long, even though many people found it silly or downright objectionable? In the book, I respond to this query by considering the diverse gains that people plucked from the science. I consider the social trappings of authority, and the ways that people assert and shore up status as holders of knowledge through the tools of language, dress and personal influence. A ‘Professor’ or ‘Madame’ of the science dressed and spoke in a particular way. In the most fortuitous moments, such skills responded to an enduring human urge among customers (and arguably people overall) to better understand their own strengths and foibles, and to really know what goes on in the heads of other people.

The Tasman World was also a stolen world. European settler-colonists dreamt their colonies into being on the country of distinct Aboriginal groups and Māori Iwi with connections to place that arc back into Deep Time. The European world devastated other worlds. This truth weaves through crucial research into phrenology’s role as a racial science and its material legacy in the Ancestral remains collected for science by museums and scientific institutions well into the mid-twentieth century. It ripples through my first book, The Hanged Man and Body Thief: Finding Lives in a Museum Mystery (Monash University Publishing, 2015).

As I researched that first work in what now seems like another life, I also gained insights into phrenology’s plural lives, including its roles as a form of popular entertainment and as a language for describing people that surfaced in books, music and culture. Explicit discussions of race featured less in lecturing than I expected, with stage content often focused on partner selection, child rearing and the visual media of lantern slides and lightning sketches. Phrenologists were largely beholden to customer urges; and as is often the case, paying customers wanted most to hear about themselves. I also witnessed a black phrenologist lecturing to Māori audiences, considered Aboriginal audiences watching phrenological lectures on a mission, and read about phrenology twinned with fortune telling in the demi monde of markets and arcades of colonial Melbourne. In the settler-colonies, many such interactions were still inextricably about race, and often pulsed with anxiety about the forging of a strong white nation. But the power dynamics inherent to such moments were often more complex than those evident in collections of human remains.

The historian Roger Cooter, in his germinal text – The Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the organisation of consent in nineteenth-century Britain (Cambridge University Press, 1984) – observed that histories of phrenology date back to the mid-nineteenth century. The science continues to serve as a common prism for understanding knowledges in formation and their reception. Largely, this is because phrenology retained a place in various societies for so long, even when faced with widespread scepticism, and because it could serve many ends. It was not one thing but a number of practices assembled in a toolbox. And so too do its histories pose different questions that settle within the boundaries of the places and periods that they examine.

Western biomedicine retains its dominant position as a source of authority in many national and regional contexts, despite the ruptures of the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2019. But how people assemble knowledge about their bodies and minds remains personal, creative and often surprising.

Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World responds to our present by inviting readers to consider the social meanings and tenuous power gained from scraps of natural knowledge. Authority accrues in many ways, especially when it responds to a nagging human need. Here was a science that yielded pithy insights into the mind – of the individual client and, even more seductively, of the unknowable other. At its most enigmatic, it was a serious game played in the fault lines of settler-colonial power.

Latest Comments

Have your say!