In the evening of June 16 , 1940 , a reconnaissance regiment of the ninth German tank division appeared at the eastern gates of the French city La Charité-sur-Loire. Paris had fallen two days earlier, and the French army was preparing a new defensive position on the Loire River. Establishing bridgeheads on the left side of the Loire was therefore a high German priority. After disarming 500 French soldiers in La Charité, the reconnaissance regiment moved to capture the bridge linking the town with a suburb on a small island in the Loire. A French sapper team, however, blew up an arch of the bridge when German motorcyclists appeared, and thirty French soldiers opened fire from the island. In several hours of combat, the Germans drove these soldiers away and captured a small, still intact bridge between the island and the mainland west of La Charité. The reconnaissance regiment guarded the bridges without incident until it was relieved by advance sections of the 205th Infantry Division in the evening of June 18. These men immediately tried to take possession of a bridge over a canal two kilometers west of La Charité, but they encountered resistance and took the bridge only after a second attack the following morning. Meanwhile, other soldiers of the 205th Infantry Division discovered at the station of La Charité a train with top-secret French documents, which Hitler used in a July 19, 1940, speech to claim that France, Britain, and Belgium had planned a joint attack on Germany. In the evening of June 19, German construction specialists made the destroyed arch of the bridge passable again. Fighting near La Charité had ceased by that time.

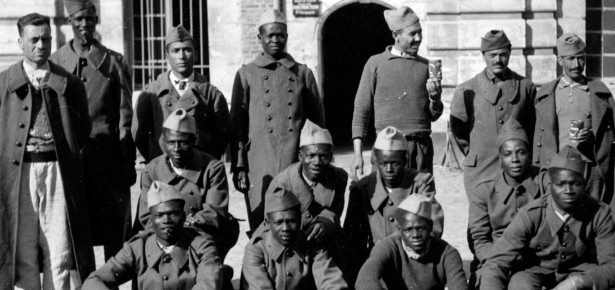

The French defenders in this sector were dispersed soldiers collected at the bridge of La Charité just before the arrival of the Germans and a small group of reinforcements from a military school in Bourges, a town farther west. Some of the soldiers from Bourges were black Africans. One of them reported that the Germans, after gathering the prisoners, selected the black soldiers and lined them up against a wall to massacre them. The black soldiers briefly conferred and agreed that they would die shouting “may France live” and “may black Africa live!” Fortunately, a French lieutenant intervened, pointing out that the Germans themselves had congratulated the French for their spirited defense, and he convinced the Germans not to carry out the massacre. The black soldier who reported the incident after the war was Léopold Sédar Senghor from Senegal, at that time a teacher at a high school in Saint Maur-des-Fossés outside Paris and already a renowned thinker who had published articles and speeches about black identity (négritude).

After capture, Senghor was sent to several POW camps in northern and northeastern France. He suffered in these overcrowded and undersupplied initial camps, but he was spared the harsh transfer to Germany that 40,000 prisoners from the French empire had to endure in June and July 1940 before most of them were sent back to France on Hitler’ s orders. Not much more than an anecdote is known about the first four months of Senghor’ s captivity: According to a white French prisoner, a German guard approached him and began rubbing his finger against Senghor’s skin, trying to see if the dark color stuck to his finger. The guard was dumbstruck when Senghor said in German, “Nein, das ist nicht Kohle!” (“ No, this is not coal!”). Senghor was formally registered as a POW in the camp of Poitiers, Frontstalag 230 , in October 1940 . (Frontstalag was the term for German POW camps near the front and in occupied countries.)

From this moment on, an anonymous report by Senghor from June 1942, which I identified, gives a fuller picture of his captivity experience. In Poitiers, Senghor experienced a brutal camp commander who once ordered a guard to shoot and kill a hungry black prisoner who had “ stolen” a potato. The food rations were insuffi cient and of poor quality (rutabagas and half-rotten potatoes), and the prisoners – predominantly French colonial soldiers – were housed in drafty hangars without heat in a camp that turned into a vast swamp after every rain. Senghor described these conditions in the poem “ Camp 1940” that he published in the collection Hosties noires (1948):

It is a huge village of mud and branches, a village crucified

By two pestilential ditches.

Hatred and hunger ferment there in the torpor of a deadly summer.

It is a large village surrounded by the immobile spite of barbed wire

A large village under the tyranny of four machine guns

Always ready to fire.

And the noble warriors beg for cigarette butts,

Fight with dogs over bones, and argue among themselves

Like imaginary cats and dogs.

Download the full excerpt here.

Latest Comments

Have your say!