The ninth post in the series The Horse in Human History

Gaucho from Argentina, 1868 (Wikipedia)

The story of the Spanish conquest of the Americas is well known. In a hemisphere where the horse had been extinct for 9,000 years, the conquistadors’ steel swords and firearms were more than a match for Amerindian obsidian-studded clubs and bronze mace heads; the invaders’ imposing warhorse moreover helped recruit disaffected allies of the Aztecs and Incas to the side of the Conquest. Old World diseases also quickly decimated the indigenous population. As a result, first Cortes then Pizarro successfully overthrew the New World high civilizations in a matter of months. The immense wealth plundered from the Americas tripled the amount of gold and silver circulating in Europe. It stimulated an explosion of economic and intellectual activities. And it financed foreign wars that finally toppled the Ottoman giant

But, as the frontiers of New Spain moved north, the horse was reintroduced into the very canyons and mesas of the Southwest where Equus had initially evolved four million years earlier. During the 1680-90 Pueblo revolt, hundreds of Spanish horses escaped from the upper Rio Grande valley into their natal environment, where they prospered and multiplied to form the great mustang herds that forever changed the history of the American West. Previously, the prairies were populated only along forest and riverine fringes. Now, however, equestrian Amerindians moved out onto the high steppe in the seasonal buffalo hunt. There the horse served both in riding and transport, hauling, by travois four times the load of a heavily burdened dog, and twice as fast. Thus when Euro-american pioneers fanned out westward across the prairies, equipped with the same covered wagons and domesticated animals with which Indo-Europeans six millennia earlier had expanded across the Eurasian steppes, they faced Amerindians very different from the ones encountered by Cortes and Pizarro. No longer pedestrian, Plains tribes strongly resented foreign invasion of their prime hunting territories and energetically resisted settler advance, their swirling mass of riders thundering across the prairie to unleash a rain of arrows.

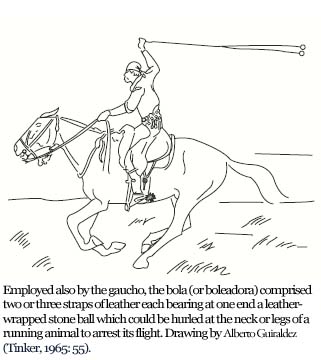

In amazing parallel to events in North America, there was a comparable explosion of horses on the grassy plains of South America. In southern Chile, the conquistadors encountered fierce resistance from Araucanian tribes, who capturing Spanish horses, had transmitted the horse eastward across the low mountain passes of the southern Andes to the pampas (steppes), where the horse proliferated. In 1598 the 300-year-long Arauco war began, as intermediary Pehuenche tribes traded huge numbers of horses back across the cordillera, affording the Chilean Mapuche cavalries a decisive military advantage over the colonists, who, without access to the pampas had far fewer horses. As Spanish settlements were subjected to unrelenting raids, thousands of women and children were abducted as slaves. In fact, so high was the rate of miscegenation that the Chilean Coliqueo who traversed the pampas as far as the Atlantic to raid Buenos Aires were known as “Blonde Indians.” Riding with wooden bits, saddle, and toe stirrups for their bare feet, Amerindians also adapted their bola weapon to equestrian hunting.

In amazing parallel to events in North America, there was a comparable explosion of horses on the grassy plains of South America. In southern Chile, the conquistadors encountered fierce resistance from Araucanian tribes, who capturing Spanish horses, had transmitted the horse eastward across the low mountain passes of the southern Andes to the pampas (steppes), where the horse proliferated. In 1598 the 300-year-long Arauco war began, as intermediary Pehuenche tribes traded huge numbers of horses back across the cordillera, affording the Chilean Mapuche cavalries a decisive military advantage over the colonists, who, without access to the pampas had far fewer horses. As Spanish settlements were subjected to unrelenting raids, thousands of women and children were abducted as slaves. In fact, so high was the rate of miscegenation that the Chilean Coliqueo who traversed the pampas as far as the Atlantic to raid Buenos Aires were known as “Blonde Indians.” Riding with wooden bits, saddle, and toe stirrups for their bare feet, Amerindians also adapted their bola weapon to equestrian hunting.

During the seventeenth century a new equestrian adventurer emerged, the gaucho. In great expeditions, gauchos set out across the pampas to hunt feral cattle for their hides and tallow – tallow that would provide candle illumination to the European masses. Attacking the herd at a gallop, they deftly slashed the hamstrings of the beasts, in a few days assuredly downing a thousand. Hunt accomplished, the men gathered to gorge on barbecued carcasses of beef accompanied by mate beverage. After this lavish banquet, the gaucho fell asleep beneath the stars, the poncho his blanket, the saddle his pillow.

But the gaucho was a critical force in the fight for nationhood. In 1771 gaucho cavalry repulsed Portuguese invaders from Argentina and in 1807 joined Santiago Liniers’s regular cavalry to recapture Buenos Aires from the British. In the Argentine Wars of Independence. the gaucho guerrillas fought with fanatical ferocity, audaciously capturing Spanish generals with their formidable bola flinging weapon. Their counterparts in the north, the lancers of the llanos (prairies) of Colombia and Venezuela, also vigorously combated the Spanish Royalists. Their caudillo-chieftain Jose Antonio Paez commanded 1,000,000 cattle and 500,000 horses and mules in the Apure and in 1819 overwhelmed the Royalist cavalry at the battle of Las Queseras del Medio. Without the support of Paez’s intrepid llaneros, it is doubtful that Simon Bolivar would have succeeded in the national war of Liberation against Spain.

Reference: Tinker, Edward Larocque 1964 Centaurs of Many Lands. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Latest Comments

Have your say!