We all know that democracy is in trouble. We are less sure what to blame. Political donations and invisible algorithms? The rise of a culture of personal rights replacing a culture of community? Or from the opposite perspective, the rise of a thing called ‘populism’. In Democracy, Theatre and Performance I look at a political problem from the perspective of a theatre historian interested in the art of the actor. For centuries, actors have been the victims of prejudice, branded as professional liars. It all seems to have started with Plato, who complained about the evils of rhetoric, a corrosive force in Athenian society that culminated in the death of his mental, Socrates, the man never afraid to ask awkward questions. In place of rhetoric, a set of techniques you could pay someone to teach you, Plato argued for deliberation, reasoned debate. There is a flaw in Plato’s argument, and it is not simply that humans are not very good at being rational. In the end, democratic debate is about the good life, and there is no rational way to pin down a life worth living. Even if we set religious objections aside, we still have to explain why a person might want to climb a rock face, player a sonata, or kick a piece of leather between two posts. No theory of well-being accounts for the emotions generated by these activities.

Rationality is a condition of democratic debate because it institutes a willingness to listen, and reach for a common language. But in the end everything comes back to emotion. As a theatre specialist, sometime author of a book about the clown, I watch with dismay when a politician tries to argue rationally with Donald Trump. People love a trickster, a rogue like themselves, and find it much harder to empathise with someone who trumpets their own virtue. In Britain, people voted disastrously (now the view of most) to leave the European Union. A rational argument was pitted against an emotional argument and, predictably in hindsight, emotion won out. Of course, rationality can impart feelings of comfort and reassurance, while emotions can alienate if the performer has not has not managed to convert ‘my feelings’ into ‘our feelings’. Britain at the time of writing this blog seems destined soon to have a Labour government, on account of anger with the status quo and a simple emotional desire for change. The Labour leader is a skilled lawyer trained in deliberation, with either little interest or little ability in the art of public persuasion. And yet public persuasion is a necessary condition of democracy, to convince individuals that they are part of a we, not an amalgam of I’s, and need to surrender something personally advantageous for the sake of that we.

Democracy is a theatrical art, and sincerity is no use unless it is performed, which leads us to a conundrum: if sincerity is performed, is it still sincere? To address this riddle, we need a historical lens. Democracy took one particular form in polytheistic Greece, where you couldn’t turn to the gods in order to tell right from wrong, and where mountains divided one community from another. It is no coincidence that theatre began in the same environment, giving semiliterate voters insight into manipulative arguments that led to destructive outcomes. In the era of Protestant Christianity, democracy was born anew around the principle of representation. Puritans who rejected the role of bishops and elected their own ministers to serve their congregation were naturally drawn to the idea they should elect their own rulers in the secular sphere. The idea that you should consult your conscience in the privacy of your own heart fed through to the privacy of the ballot box. Part of the puritan mindset, however, was to seek the same sincerity in your elected representative as you found, or thought you found, in your own heart, and the puritan desire to weed out hypocrisy has left undoubted traces in the culture wars of the present. Catholic France had a different mentality, looking back to Republican Rome with fewer anxieties about being performative. Rousseau, the citizen of Protestant Geneva, however, had a significant impact in convincing French men and women that they were in the first instance individuals, not fragments of a collective. After some success as a dramatist, Rousseau became an eloquent foe of theatre.

The hooking of democracy to Christianity and individualism was a challenge for liberated colonies which saw democracy as a system they had too long been denied. My case study is India. Gandhi was expert in performing his own sincerity, challenging the colonial powers to find flaws in his performance. He hated the idea of parliamentary representation, because that implies the performance of a role, and looked for an authentic Indian alternative that would put community before individualism. In practice, however, western democratic individualism became the only plausible solvent for intercommunal tensions. In his person, Gandhi struggled to reconcile his devout Hinduism with his determination to be the universal Indian. It was a problem of performance. Political society requires that human beings should be actors, engaged in what is seen to be a piece of theatre. And theatre is not a bad thing. Indeed, for many irrational devotees of the Arts like myself, it is one of the things that make life worth living.

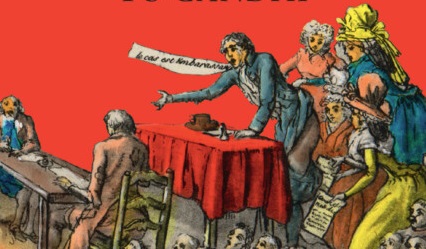

My cover image is a satirical print depicting Robespierre addressing the Jacobin club. He is opposing war, and women are debagging him, mocking him for his presumed cowardice. It is not always comfortable to participate in a culture of public argument. Robespierre gave up on the endeavour, convincing himself that he alone was the best judge of right and wrong. Many have followed him in that conviction.

Democracy, Theatre and

Performance by David Wiles

Latest Comments

Have your say!