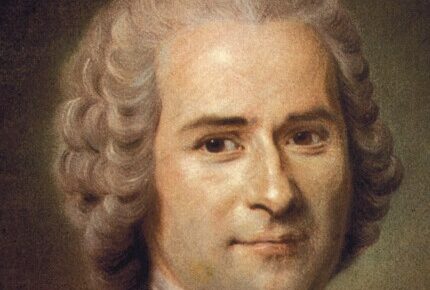

2024 promises to be a year of decision for democracies worldwide, with important elections scheduled in Taiwan, Venezuela, Mexico, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Several of these elections are taking place in countries with relatively fragile democracies, and where the voters themselves are uncertain about the political health and stability of their own countries. While there is much to be learned from contemporary political scientists about what it takes to maintain a thriving democracy, there are also reasons to consider what might be learned from earlier thinkers, among them Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

On first glance, Rousseau may seem like an odd choice for thinking about democracies. After all, in his most celebrated work of political philosophy, The Social Contract, Rousseau lamented that “if there were a people of Gods, it would govern itself democratically. So perfect a Government is not suited to men.” And further, Rousseau was deeply skeptical of delegating the task of legislating to representatives, who threaten to substitute their own will for the general will of the people themselves. The infamous reference to citizens being “forced to be free” poses a further challenge.

Yet for all Rousseau’s puzzling and occasionally unsettling formulations, partisans of democracy have never ceased appealing to his authority. The reasons for this enduring presence are various: Rousseau offers detailed reflections upon how the common good can find itself placed– or displaced– at the center of political life; how inequalities of wealth can threaten the health and even the survival of a free society; how the precise means of voting and counting votes affect the result, and how the basic morals and spiritual convictions of a people shape its politics, in which (broadly understood) some form of or analogue to civil religion will inevitably be entwined with political order.

Perhaps above all, the kind of modern democracy that Rousseau helped to invent was one that would reflect the people’s will, or as he called it, the general will. While the term is highly contested, Rousseau helpfully clarifies its meaning by contrasting it against the private or particular will. Every citizen has both a private and a general will. The private will reflects one’s personal or even selfish interests – such as an interest in acquiring money, status, power, and everything that might help us secure various sorts of goods over and against others. The general will, by contrast, is our interest in the common good. It may be the private interest of the factory owner, for example, to pollute the local river. But it is his general will that everyone in the community should have access to clean drinking water. A thriving community – what Rousseau, in fact, calls a “republic” – is one in which the laws reflect the general will, rather than an individual’s or group’s private will.

What does this mean come election day in the various upcoming elections of 2024? For individual democratic citizens, it means that, for Rousseau, they should be voting not in order to promote their private or personal interests, but a more general flourishing that can be encouraged by thinking about politics in both a broad and fundamental way, as Rousseau and other political philosophers encourage their readers to do. Republicans (with a small “r”) should not vote with their own pocketbooks foremost in mind. Perhaps above all, a vote cast with an eye upon one’s business interests, or as a means to express anger or resentment, is a vote that will ultimately subvert the best purposes of political life. Votes should be directed toward those policies that one honestly and rigorously believes serve the good of all citizens.

For Rousseau, democracy’s greatest virtue is the fact that the people themselves know the common good better than any segment of the population, much less a single ruler. But there is also a real danger that the people may not actually vote for that good. He acknowledges in his Social Contract, that while “the general will is always upright, . . . it does not follow that the people’s deliberations are always equally upright.” Most disconcertingly, as he cautions in his Discourse on Political Economy, the people are always in danger of being “seduced” by “some few skilled men [who] succeed by their reputation and eloquence to substitute for the people’s own interest.” Opportunists and demagogues stand poised to manipulate even earnest citizens of good will – eager to persuade them that the interests of the few are actually the interests of all.

Of course, there are other threats to the people’s deliberations, from electoral procedures ill-suited to a given political community, to conflict about the fundamental moral and spiritual sensibilities of that same community. Not least, for Rousseau, one of the greatest forces of social division, is the presence of deep and abiding economic inequalities among citizens. While Rousseau does not demand in his Social Contract that for each citizen, “wealth should be absolutely the same,” he holds that no citizen should be “rich enough to buy another.” A thriving republic will “bring the extremes as close together as possible; tolera[ing] neither rich people nor beggars.” While these sorts of claims have mostly been sidelined during a long era of neoliberalism, Rousseau was not alone in making them among his contemporaries, at the beginning of the modern democratic age. For example, James Madison would subsequently argue in Federalist No. 10 that the primary source of divisions between people will be economic ones. The greater the divide, the fiercer the divisions.

Those divisions, for Rousseau, will corrupt the general will – crowding out its quiet voice in favor of those fierce moneyed interests, on the one hand, or violently lashing out against those taken to be wealthy oppressors, on the other. Inequality, for Rousseau, inflames selfishness, resentment, and the social divisions that threaten to undermine democracies – not just in new democracies, but in established ones like the United Kingdom or the United States. Whatever our conclusions about the common good, Rousseau reminds us that it is this general good– and the public-spiritedness that seeks and preserves it– that serves as the starting point for democratic flourishing. In agreement and disagreement with his reflections on the nature of that good- and the ways in which it can be both achieved and sustained– readers can enrich and deepen their own thinking about these crucial political questions, in a crucial political year.

Latest Comments

Have your say!