With all the recent interest in the International Criminal Court – can it prosecute Putin? Will it intervene in the Hamas-Israeli War? Will it finally investigate crimes in Venezuela? – it would be easy to forget that this court is not simply a juridical black box for war criminals to be sent to. It is also an office: a place where prosecutors devise strategic goals and write them up into glossy plans, where court officials meet with their supervisors to discuss their performance, and where lawyers meet – literally and figuratively – on a terrain of legal argument that laces foundational questions of justice, sovereignty, and redress for victims with claims about court capacity and scarce resources.

These obscure aspects of the court’s everyday life I was not prepared for when I first entered the ICC building as an intern some years ago. Yet after only a little time spent there, it became commonplace to see legal officers leave a meeting with a judge and enter another with their supervisor to talk performance appraisal. The language of violence, criminality and procedural technicalities combined with words like auditing, indicators and restructuring exercises. I could not then put words – or theories – to what I was seeing but figured that there might be more than mere coincidence to the alchemical blend of these two discourses: anti-impunity and management.

The Justice Factory is an attempt to think through the relationship between anti-impunity as a legal project pursued by the ICC and the myriad managerial practices it invokes and deploys in its name. This is no philosophical exercise: in April 2019, ICC judges relied on the ‘realities’ of organisational stability and limited financial and human resources to argue against opening an investigation into potential US and government crimes committed in Afghanistan after 2001. At the time, many academics condemned the judges for such extra-legal reasoning and for positioning themselves more as budget managers than as legal experts.

Yet when I began to study the court’s case law, managerial reasoning and management tools turned up in many legal debates – over court logistics, but also situation and case selection, arrest and surrender activities, and victim participation procedures. From relying on audit reports as an argumentative source to formulating a streamlined one-page victim application form, it seemed as though the ill-fated Afghanistan decision was only the tip of the iceberg. This is perhaps what eminent judge Antonio Cassese was alluding to when he lamented in 2006 that a court of law is not a factory.

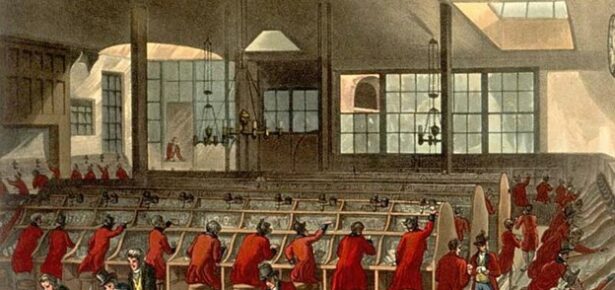

I dove into the court’s digital archive of reports, plans, and papers. From these records, it became clear that the courtroom was not the only place experiencing a managerial turn, but the wider organisation and its professional experts too. Questions soon arose: where did the court’s managerial practices originate? In institutions as diverse as the cotton plantation, the steel factory and the United Nations. Did they do what they claimed, namely optimise court functioning? Not quite. And in what ways does the global justice project get reoriented when it is filtered through the exigencies of efficiency, cost-effectiveness and performance?

As this final question suggests, these are topics The Justice Factory tries to grapple with by attending not only to the functional intent of management but its productive power – the contexts it fashions, the problems it sets up, the solutions it offers, the identities it mediates, the arguments it reconstructs and the meanings of global justice it trades in. Cassese’s statement that such a court is not a factory has been muffled by the thick managerial infrastructure that now makes up this court. There, management’s power is revealed between the lines of successive strategic plans, in the lists and tick-boxes on an employee appraisal form, in the lawyer’s desire to escape from the intractable tensions confronting international criminal law, and in large-scale restructurings such as the Registry ReVision project. Formed by a curiosity, the book makes these managerial practices look strange to better understand where they came from, how they work, and what is won and lost once justice professionals arrive at their desks to manage the great global justice experiment.

Latest Comments

Have your say!