What comes to mind if you think about the use of Shakespeare during wartime? Perhaps it is Laurence Olivier’s famous 1944 cinematic adaptation of Henry V, prominently dedicated to the troops of Great Britain. But what is often overlooked is just how embedded Shakespeare has been in wartime culture, in Britain and globally, since at least the eighteenth century. He was fought over on stage and in politics by supporters and opponents of the French Revolution. He was claimed as one of Germany’s own writers – unser Shakespeare – during the First World War, an appropriation that also affected his mobilization in Britain. He has been a pivotal writer for resisting Russian imperialism throughout Ukraine’s history and has been repeatedly invoked by Ukrainians, including President Zelenskyy and scholars such as Nataliya Torkut, during the ongoing Russian invasion.

The history of Shakespeare’s wartime performance is a revealing one that helps to shed light on the complexities of conflict and some of the political issues at stake. This history is not, however, a linear or neatly progressive one. Some accounts of wartime theatre have reinforced simple binary oppositions and clear ideological views: a production is pro- or anti-war, reactionary or revolutionary; it expresses support for one side of the conflict but not the other. But what surprised me the most when researching this book is the fact that many wartime productions are much more equivocal than these labels and narratives suggest. Productions of Shakespeare’s plays, like the texts themselves, do not have single or fixed meanings, and often involve individuals with different sympathies and agendas. Some see the theatre as a means of escapism or as a platform to process their experiences of war, while others use it to express their political views that may exist in tension with the perspectives of others involved in the same production and those who watch and respond to it.

For example, during the French Revolutionary Wars, a production of Macbeth at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane could be associated with the anti-revolutionary sympathies of John Philip Kemble, its star actor, who sometimes inserted jingoistic additions into Shakespeare’s plays to support the war effort against France. The play features an act of regicide – Macbeth’s murder of Duncan in Act 2 – a dramatic parallel that was mentioned in contemporary publications that condemned revolutionary action. But this same production and the theatrical space of Drury Lane were also linked in the public imagination with the theatre’s proprietor, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who had very different political views and spoke out against the war with France. He could help to activate the anarchic appeal of the play and the way it could be used to oppose established authority. To give another example, during the Second World War, actor Sybil Thorndike toured Wales and north-east England with a production of Macbeth that positioned its central character as a dictator resembling Hitler and featured a new ‘induction’ that made this link and the relevance of the play explicit. Thorndike was, however, a pacifist who opposed military action, so rather than this production expressing clear support for Britain’s war effort, it could, for one of its main production agents, express both condemnation of fascism and military aggression, as well as serve Thorndike’s socialist sympathies by bringing Shakespeare to less privileged parts of the country. Because theatre is a communal activity, it can, during a period of crisis, bring together individuals with different perspectives on the conflict and shed light on the complexities and ambivalences within political thought.

Wartime Shakespeare: Performing Narratives of Conflict concentrates on this complexity and the malleable roles that Shakespeare has played on different wartime stages, while also addressing his fragmented and contested relevance as a figurehead of British cultural hegemony. My book sets out a new methodological framework that shows how networks of production and reception shape wartime theatre, drawing attention to the participation of actors, directors, designers, politicians, propagandists, critics, and audiences. It offers the first transhistorical study of wartime Shakespeare in performance, starting with the Essex Rising in 1601 during the Nine Years’ War (1593-1603) and ending with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in March 2022. It incorporates chapters on the Seven Years’ War (1756-63), American Revolutionary War (1775-83), French Revolutionary-Napoleonic Wars (1592-1815), Crimean War (1853-56), First World War (1914-18), Second World War (1939-45), and Iraq War (2003-11). Each chapter examines how wartime performances of Shakespeare help us to understand issues at the heart of each crisis and the experiences of individuals connected to it.

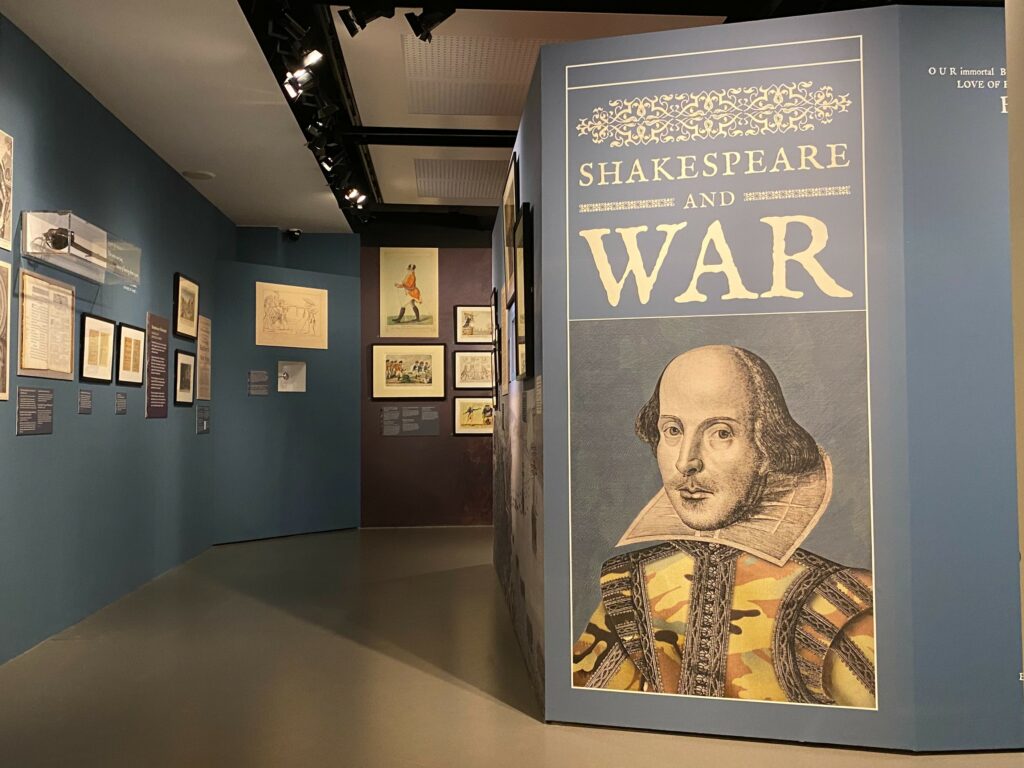

My monograph is also linked to a book collection that I co-edited with Sonia Massai called Shakespeare at War: A Material History (CUP 2023) and a free public exhibition, ‘Shakespeare and War’, at the National Army Museum in London that we co-curated. Each chapter within the edited collection takes a material object linked to a wartime use of Shakespeare as its focus, which becomes a jumping-off point to ask broader questions about the conflict and Shakespeare’s relevance. An emphasis on material evidence similarly underpins my monograph, Wartime Shakespeare, and one of the key factors that I was keenly aware of during my research was the extent to which our access to ‘wartime Shakespeare’ is shaped by material loss and absence: that our understanding of its significance is limited by surviving evidence and also by our critical acts of selection – of choosing which materials to present and foreground – which should be continually reappraised. Many items that are discussed within my monograph or the edited collection feature within our exhibition ‘Shakespeare and War’, open from 6 October 2023 to 1 September 2024, and include a rare playbill from a British military production of 1 Henry IV in Philadelphia during the American Revolutionary Wars, theatrical programmes for a Shakespeare Tercentenary Festival in Ruhleben Internment Camp during the First World War, and materials from the Ivan Franko Drama Theater’s production of Hamlet during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Carl von Clausewitz famously remarked that war is the continuation of politics by other means. It could be argued that wartime theatre offers a platform for the continuation of politics and war by other means.[1] This continuation is often ambivalent, malleable, and polyvocal; but one other aspect that surprised me during my research is that wartime theatre rarely seems to change people’s minds about a conflict. Theatre tends to catalyse pre-existing sympathies and political views, rather than alter them. Productions of The Merchant of Venice, for example, can build on and entrench the anti-Semitic views of those involved in its staging or in the audience. Conversely, productions of Henry V (such as Nicholas Hytner’s 2003 production at the National Theatre, which responded to the coalition invasion of Iraq) can lead a ready audience and production team to think more deeply about a conflict, its justification and conduct, and questions of complicity and responsibility. When looking ahead to the future of ‘wartime Shakespeare’, we can expect to see theatre used to reinforce already-held views, a process that sheds light on the sympathies of those connected to it and the crises at the heart of a conflict – but what is crucial to emphasize is that these views are not singular or uniform for one production. Monadhil Daood’s Romeo and Juliet in Baghdad examines the consequences and unresolved tensions in Iraq following the withdrawal of US forces in 2011, but prompted different responses when the production was staged in Stratford-upon-Avon and in Baghdad, where its immediacy and urgency were much more pronounced. What I felt most acutely from working on this book was the need to recognize the diverse motivations, experiences, and political aims that underpin wartime Shakespeare – in brief, to be aware of the structures of production and reception that shape wartime theatre and how they can help us to understand the complexities of conflict itself.

[1] James Thompson, Jenny Hughes, and Michael Balfour, Performance in Place of War (London: Seagull, 2009), p. 2.

Latest Comments

Have your say!