The Middle Ages is a story modernity tells about itself. Ideas of rebirth, or of an “enlightened” modern age, or of a supposed rejection of primitive superstition in favor of rational thinking, often depend on the idea of a cruder past that a more glorious present can be contrasted against—and often overstate the achievements of a conflicted, ever-shifting modern world. So ingrained are these associations that actually-modern brutality can be labeled with the pejorative “medieval,” while actually-medieval cultural touchstones may be called “ahead of their time.” Even within cultural histories of the Middle Ages, accounts of new developments sometimes assume stark contrasts with the past where reality was more complex. Decades ago, in his history of medieval culture, R. W. Southern contrasted the “ceaseless round” of early medieval monasticism, in which individual identity was, he claimed, subsumed into that of the community, against the powerful new currents of religious feeling said to arise in the twelfth century. And while this century did witness important new events and new thinkers, Southern’s account set glorious innovation against a grim and simplified past—a rhetorical move running parallel to the contrast between modernity and the middle ages. The stories we tell about the past may begin in different settings, but share a tendency to jettison earlier centuries as primitive in order to shine a brighter light on something supposedly new.

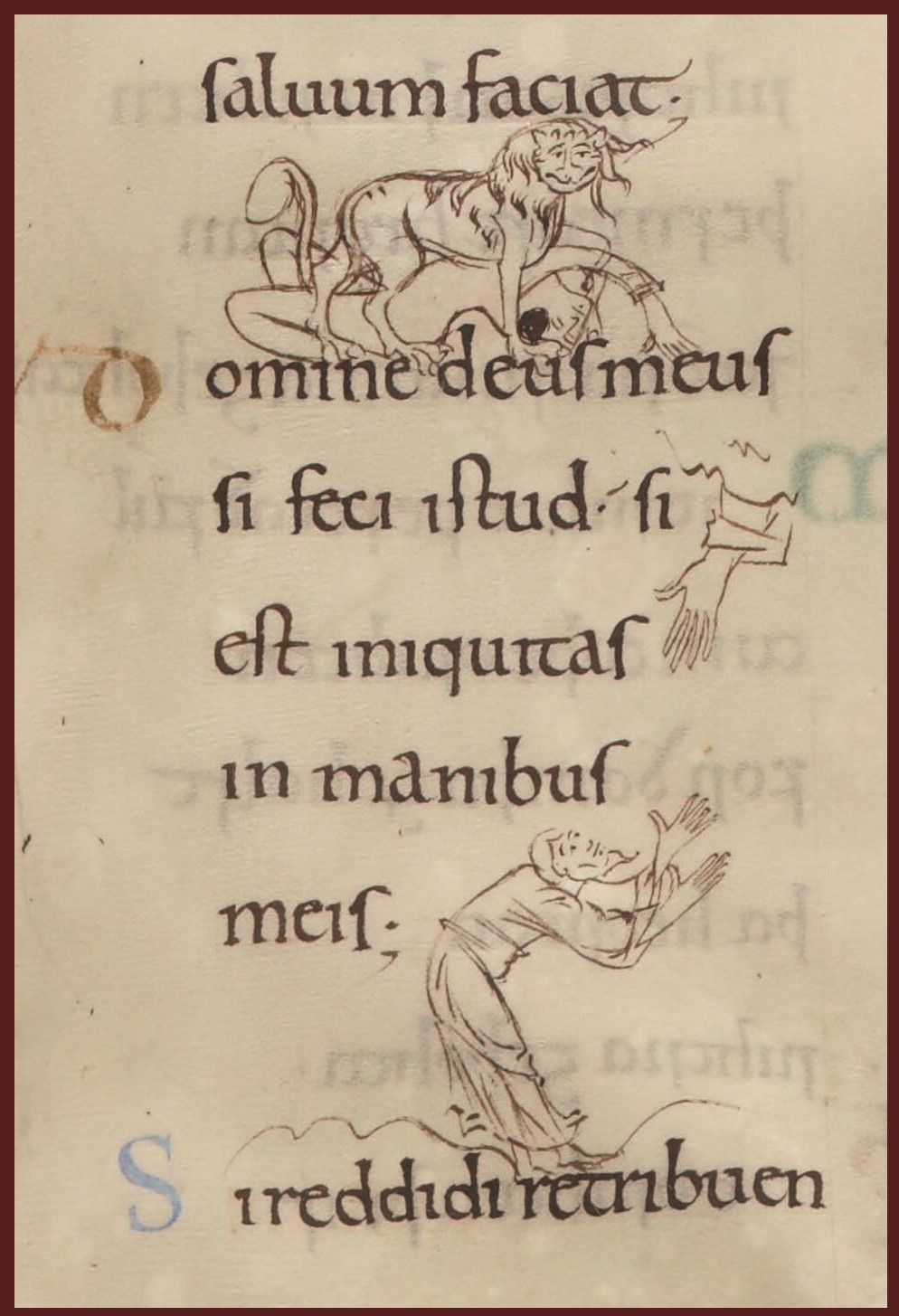

In Forms of Devotion in Early English Poetry, I argue for a more complex account of literary and religious history, showing how these supposedly new religious feelings often actually continue overlooked conventions from centuries before. Forms of Devotion traces conventions of profound devotional feeling in English poetry from across the centuries, well before the Norman Conquest of England in the eleventh century and the supposed rise of affective devotion in the twelfth and carrying on into the thirteenth. While deeply felt religious devotion in medieval Christianity (what has become known as “affective devotion”) actually stretches back to at least the desert fathers of the fourth and fifth centuries CE, if not in fact to the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament itself, we can better understand the significance of subsequent religious developments by tracing the longer yet more localized traditions that underlie them, particularly those that have remained distant and opaque to modern readers and scholars.

My book begins with poems usually thought to exemplify just how little the earliest English devotional poems emphasized feeling. For example, while later affective devotion typically portrays the suffering of Christ and the Virgin Mary, eliciting sympathy from audiences explicitly, the Old English poem The Dream of the Rood portrays a warrior-Christ who mounts his own cross with alacrity and never weeps or speaks. But as I show, the poem draws upon vernacular poetic tropes of a fallen lord—elegiac lament poetry where the follower expresses grief for the lord, in spite or perhaps because of the lord’s stoic endurance: “Eall ic wæs mid sorgum gedrefed / forht ic wæs for þære fægran gesyhðe” (I was completely afflicted with sorrows, I was afraid because of that fair sight.) In The Dream of the Rood, that lord has become the Lord. It is the speaking Cross in the Dream and the Dreamer who witnesses it who grieve and weep, lamenting the weight of sin and the magnitude of the Lord’s sacrifice. In this way, the poem offers an early sophisticated model of sympathy by displacing profound feeling onto a character with whom readers may empathize, and whom they might emulate in their felt responses to the poem, too.

Across the book, I seek to demonstrate how vernacular poetic tropes combine their conventional associations with those of devotional tropes, creating a hybrid aesthetic. Relying on connotations of poetic formulas and type scenes established in other contexts, poetic devices that would have been immediately recognized and immediately evocative to their original audiences have by that same token remained opaque to modern readers.

In subsequent chapters, I consider the images of beauty and material luxury in poems on paradise, I trace the distinctively English convention of a soul and body dialogue that actually only offers the soul’s monologue, and I consider the contrasts in Marian laments both before and after the Norman Conquest. The particular hybrid tropes and topoi, and the recombination of these with developing tropes and topoi introduced to England after the Conquest, show how early English affective piety developed into that which has been more readily recognized—depictions of Christ as sweetheart, for instance, or devotional sentiments riffing on the conventions of ballads and love lyrics. As much as these represent departures from Old English vernacular poetic conventions, they also reveal surprising continuities, and expectations that earlier tropes could still be recognized.

Forms of Devotion considers the tendency for the stories we tell about the past to prioritize accounts of rupture and innovation at the expense of more complicated histories, histories that account for how these apparently new developments revise and respond to what had gone before. We might appreciate the complexities of cultural history in part through a healthy suspicion of origin stories that valorize the new and more contemporary in contrast with a dismissal of the old. Even artifacts of the distant past have more to tell us about how the present we now take for granted came to be—and how it might very nearly have been something else.

Latest Comments

Have your say!