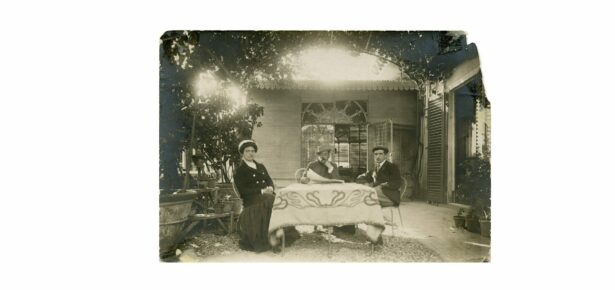

Image Credit: Elvira Puccini, Giacomo Puccini, Antonio Puccini

Archivio Storico Ricordi, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Giacomo Puccini is one of the world’s most famous and beloved opera composers and rarely a season goes by when any given opera company will not stage one or another of his works. You might be forgiven for thinking that there is little that is not already known about the life and work of this canonical composer, but in fact, scholars have only begun to pay attention to his oeuvre to any significant extent over the last three decades. Puccini has long been the victim of academic snobbery and was not taken seriously for much of the twentieth century, when musicology was dominated by a strong bias towards Austro-German repertory, and absolute (non-texted) music in particular. Italian opera tended to be regarded as frivolous and unworthy of serious study: too bound up with commerce and celebrity; too tuneful and popular.

Pioneering scholarship on Verdi in the 1980s by scholars such as Roger Parker and Philip Gossett changed all that, giving Italian opera studies a new credibility, though Puccini lagged a little further behind (and his verismo contemporaries further still) in terms of academic ‘respectability’. But the turn of the millennium saw the publication of a flurry of books about Puccini, including Michele Girardi’s scholarly life and works (Puccini, His International Art, University of Chicago Press), detailed studies of the composer’s musical language (such as Andrew Davis’s Il trittico, Turandot and Puccini’s Late Style, Indiana University Press), and considerations of individual works (including Annie J. Randall and Rosalind Gray Davis’s Puccini and the Girl, Chicago University Press). My own The Puccini Problem: Opera, Nationalism, and Modernity, published by Cambridge University Press in 2007 and awarded the American Musicological Society’s Lewis Lockwood Award, was the first major study of the composer’s reception. It examines the critical debates that swirled around Puccini at a time when the recently unified Italy was trying to establish a shared sense of cultural identity and using opera to that end.

Despite this flurry of scholarly activity, accompanied by numerous articles on the composer, there is still much that remains unknown and unsaid about Puccini and my new edited book, Puccini in Context, seeks to plug many of the gaps. The Composers in Context series pays particular attention to the broad cultural, social, and political contexts of an artist’s times, and what fascinating times they were in Puccini’s case. He was a witness to the aftermath of his country’s unification, the ascendancy of the Italian middle classes, the First World War, and the rise of Fascism. In the broader European artistic context, Modernist artists began to rip up the rulebook during the 1900s and 1910s and Puccini watched on with keen interest: although he only borrowed such innovations to a relatively limited extent, he was a more adventurous composer than most of the history books are willing to admit.

The chapters in this new edited volume, written by authors from different disciplines, backgrounds, and parts of the world, explore Puccini’s relationship with the cultural, political, and social zeitgeist of his time, both in Italy and further afield. The book also aims to shed new perspectives on Puccini the man, examining his hobbies and interests, the trends in music, literature, and drama that shaped his works, and the influence upon him of contemporary politics and religion. He took a keen interest in early film – though was anxious about his operas being adapted without his consent – and was a man ahead of his time in terms of his interest in technology. As one of the book’s contributors notes, Puccini was something of a ‘Mr Toad’ figure, dashing around the countryside in a succession of fast cars, his enthusiasm undimmed even after a serious accident.

We also learn about Puccini’s personal relationships – with relations, friends, and lovers (he was a notorious ladies’ man) – and his professional relationships and networks, with teachers, publishers, librettists, singers, conductors, and the other young composers of his generation, with whom he was thrown into intense competition. The book also takes the reader on a tour of the places that were meaningful to Puccini: not only his native region of Tuscany, but also Milan, the city where he studied, and the many foreign locations he visited both for leisure and in the course of promoting his operas. Opera has always been an international business and Puccini was a particularly well-travelled figure, supervising the performance of his works in both north and south America, as well as in Cairo. He found London full of ‘beautiful women, magnificent shows, and… abundant things to do’ and Manchester ‘A real hellhole!’ The fact that he became increasingly interested in taking commissions from foreign opera houses as his career progressed did not always curry him favour with commentators back at home.

Puccini became big business for the Ricordi publishing firm and a veritable promotional industry built up around his works, with huge efforts and sums of money being ploughed into the promotion of his works via journalistic pieces, posters, postcards and negotiations with foreign theatres. His operas were hyped by his publishers and biographers, but not always well received – critics objected to his works being, at times, too forward-looking or too ‘international’. The book pays careful attention to the ways in which the composer’s image and reputation were shaped but also to what we might call the ‘afterlife’ of his works: how he was memorialised after his death, his legacy and posthumous reputation, and the many and varied ways in which his work has been incorporated into popular culture, from the films of Golden-Age Hollywood to present-day musicals and advertisements.

The performance of Puccini’s works is, as the reader would expect, considered in detail throughout the book. We learn about the early singers who helped to shape his roles and the conductors who have interpreted his scores. Contributors appraise the great recordings of his works, both on disc and on video, and present-day staging practices – some of them inevitably informed by contemporary debates about race and gender. What Puccini’s operas ‘mean’ is constantly changing, and contributors to this book draw upon the latest scholarship in order to reflect widely – and from various different perspectives – upon the significance of his works to a new generation. There is something here to interest, intrigue and inform every Puccini fan, as well as every singer or director of his works. I guarantee that even the keenest Puccini aficionado will discover something in the pages of this book that they did not previously know.

Credit line: Archivio Storico Ricordi, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Latest Comments

Have your say!