In the opening to The Decameron (c. 1350), Boccaccio described how the ten young people who would become storytellers in his book met in a Florentine church during the height of the Black Death: “it chanced […] that there foregathered in the venerable church of Santa Maria Novella, one Tuesday morning when there was well-nigh none else there, seven young ladies […] who had heard divine service in mourning attire… […] there entered the church three young men […] and they went seeking […] to see their mistresses, who, as it chanced, were all three among the seven aforesaid”

Boccaccio’s description of young people meeting their friends to plan an escape from the plague-ridden city reminds us of a significant aspect of churches in the early modern period: their use for non-liturgical activities. As a venue for covert assignations, legal meeting, and even social events, the church interior witnessed more than mere religious rite.

Condemnations by conservative ecclesiastics provide compelling evidence that secular activities regularly occurred in the Renaissance church. Archbishop Antoninus of Florence cautioned that secular meetings, trials, and theatrical performances should not take place in church, except for religious plays. San Bernardino da Siena castigated the use of churches as locations for dances, business meetings, and courtship rituals between young girls and potential suitors. This latter activity particularly offended Savonarola, who complained that Florentine mothers “put [their daughters] on show and doll them up so they look like nymphs, and first thing they take them to the Cathedral”. In Orsanmichele, a civic oratory in Florence (Figure 1), guards were instructed to “take care that in this church men do not have conversations with women”; and a notice on the doors ordered worshippers – especially women – to leave immediately after services without rendezvousing with others to converse. In 1588, a wooden screen was installed in the building specifically designed “to obviate the problems of secret meetings and illicit conversations”, evidently euphemistic terms for sexual activities.

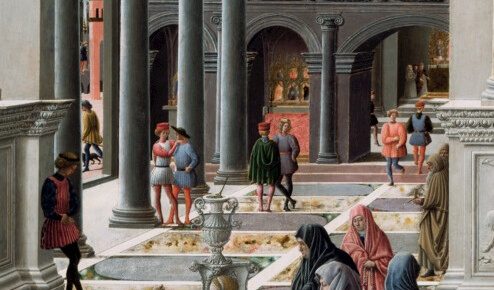

Non-liturgical activities in church, however, were not always so irreligious. With its aura of dignity and ample room for large gatherings, the church could also host secular activities of a more serious nature. For example, the local neighborhood (‘gonfalone’) of the Red Lion in Florence would hold regular meetings in the monks’ church of San Pancrazio, where they also donated choir stalls emblazoned with their insignia (Figure 2). Choir precincts for secular notarial acts sometimes involving lay women, revealing how liturgical space could function differently according to time and context. Church buildings are also documented as venues for musical concerts, war councils and university graduations.

Perhaps reacting to this diverse usage of church buildings for secular and social functions, the Council of Trent – a Catholic church council which met from 1545-63 in response to the Protestant Reformation – sought to create a more prayerful and religious atmosphere in church. In addition to banning lascivious images and music, the Council decreed that “[t]hey shall also banish from churches […] all secular actions; vain and therefore profane conversations, all walking about, noise, and clamor, that so the house of God may be seen to be, and may be called, truly a house of prayer.” In addition, Pope Pius V published a papal bull imposing monetary penalties on those who committed irreverent acts in church which disturbed divine office, including having vulgar conversations (especially with women), committing attacks, making noises, disrespectfully sitting or walking around, and turning one’s back to the holy Sacrament.

This shift – from the multifunctional church interior to one more focused on religious devotion – is an emergent theme in my book, Transforming the Church Interior in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge University Press, 2022). More broadly, the book concerns the removal in the later sixteenth century of the monumental screens and choir precincts which had previously divided the church interior into distinct spatial zones; however, an unforeseen consequence of these divisions was that they made the interior as a whole harder to surveil. When screens were eliminated, the church became more open and spacious, and religious devotion was focused on a Eucharistic tabernacle displayed on the high altar (Figure 3): a symbol of Catholic Counter Reformation dogma.

Latest Comments

Have your say!