‘You’re never really ready for it’, says Paapa Essiedu of playing the role of Hamlet, which he performed in 2016 for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production in Stratford. Essiedu’s statement captures something essential about the experience of reading or watching the play as well. The ‘heart of my mystery’, as Hamlet calls it, makes audiences, even repeat ones, not quite prepared for his story.

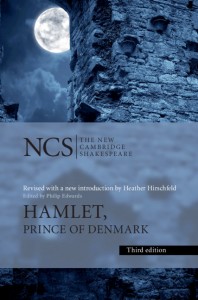

The third edition of the New Cambridge Shakespeare Hamlet readies students to encounter the charismatic Prince and the fascinating but corrupt Danish court that he inhabits. In the Introduction I examine Shakespeare’s transformation of an ancient Nordic legend into a drama that so skillfully absorbed the concerns of his own time that it continues to resonate after more than 400 years of performance and criticism. In the revised textual commentary, I provide definitions and explanations of the play’s language calibrated to the needs of twenty-first century students, and in the updated Suggested Reading, I list some of the most important, as well as student-friendly, monographs and essays on the play.

The third edition of the New Cambridge Shakespeare Hamlet readies students to encounter the charismatic Prince and the fascinating but corrupt Danish court that he inhabits. In the Introduction I examine Shakespeare’s transformation of an ancient Nordic legend into a drama that so skillfully absorbed the concerns of his own time that it continues to resonate after more than 400 years of performance and criticism. In the revised textual commentary, I provide definitions and explanations of the play’s language calibrated to the needs of twenty-first century students, and in the updated Suggested Reading, I list some of the most important, as well as student-friendly, monographs and essays on the play.

At the same time, I try to preserve for students the play’s abiding mystery and surprise. Hamlet himself is a spokesman for this kind of treatment, when he speaks about the Ghost to his friend Horatio: ‘as a stranger bid it welcome’. The Introduction thus invites students to recognize the ‘strange’ or unexpected aspects of the famous play and asks them to welcome these unfamiliar elements into their experience of the play. It focuses first on Shakespeare’s manipulations of the classic revenge plot to investigate the human experiences of love, loss, grief, obligation, melancholy, and memory. It then asks students to see the ways in which Hamlet’s antic disposition makes his behavior increasingly difficult to interpret. And it explains Shakespeare’s extensive topical references, with the arrival of the Players in Elsinore, to Renaissance theatrical conditions and the perennial conundrum of acting versus being.

Hamlet’s textual history is notoriously complex, and the Introduction treats this as another element of the play’s strangeness. It introduces students to the existence of three unique, substantive early texts: Quarto 1, Quarto 2, and the Folio editions. It works through the various debates about these texts’ relationships to one another and to what Shakespeare wrote and what his company performed, and it addresses some of the most recent theories of transmission.

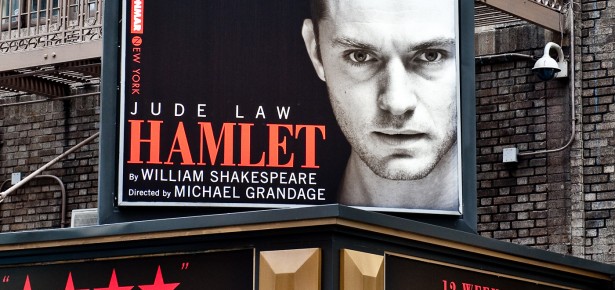

The Introduction also provides students with a broad survey of responses to and scholarship on the play, from seventeenth-century parodies to nineteenth-century Hamletism to twenty-first century historicist and psychoanalytic studies. One of the edition’s most important contributions, I think, is the inclusion of the voices of several eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women writers, such as Charlotte Lennox, Hannah More, and Anna Jameson. This emphasis on women’s responses to the play is matched in the extensive section on the play’s performance history, which not only discusses the signature performances of actors such as David Garrick, Henry Irving, Laurence Olivier, and Kenneth Branagh but also includes a discussion of female Hamlets, from Charlotte Charke to Sarah Bernhardt to Angela Winkler.

Hamlet says, ‘the play’s the thing’, and I consider the heart of the Introduction to be the scene-by-scene analysis of the drama. It orients students to the play’s unfolding plot, to its delicate balance of humor and tragedy, to the structure of its soliloquies, and to the development – or downfall – of its characters. It incorporates a range of scholarly insights into the play, from seminal readings of ‘to be or not to be’ to recent understandings of Ophelia’s fatal madness, and it provides historical context for such central issues as the status of the Ghost, the fear of death, the nature of Renaissance melancholy, the political threat of tyranny, and the complications of early modern gender and marriage. My hope is that this section, along with the others, will prepare students to be unprepared when they meet the famous protagonist, his mother Gertrude, his uncle Claudius, his once-beloved Ophelia, his friend Horatio, and the Ghost of his dead father.

Photo credit: flickr4jazz

Latest Comments

Have your say!