“Am I a logician? A writer? A mother? A woman?”

While finding my way to the Centre for the History of Science at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, I was considering this as an opening line for a text on my experiences as a woman in science, Women in STEM in general, and Marie Curie in particular.

I needed help. I’d been looking so long at my picture of Marie Curie, that I almost believed that it was real: her monumental figure, all dressed in black prepared to touch perfection in a corner of her lab, was already a closed story and allowed me little space to create anything beyond it.

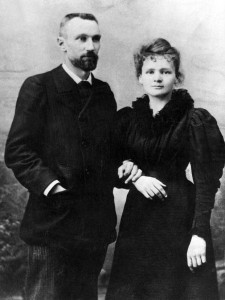

Pierre and Marie Curie in 1895. Note how Pierre is interlacing his arm in hers, and not the other way around

I was speeding to meet Xavier Roqué, expert in Twentieth Century Physics, gender-science relations, and Marie Curie. During our sixty-eight minutes interview, the rigid picture in my mind started branching into the daughter, the industrial advisor, the social activist, the sister, the politically engaged woman, the daughter in law, the medicine truck driver, the dreamer, the brilliant, brilliant, brilliant physicist and chemist, the sister in law, the polyglot for the sake of poetry, the pacifist, the loving wife (oh, she had so much love!), the mother. And moreover, as I could confirm later reading her biographical notes, all those selves were heading in the same direction!

All her (relevant) selves gathered by an inner consistency that was crucially shared by people around her, specially by her husband Pierre. The two entwined in a scientific mission that took almost all of their time, and when little Irène came, neither were willing to abandon something “as precious as shared research”. They huddled together even more.

Such passion cannot be understood only in terms of mere intellectual curiosity, both Marie and Pierre wholeheartedly believed in the social function of science, and in particular in the life-saving function of Radium, whose challenging fabrication/production process forced them to create a strong international network of contacts with industry. Marie had to take the lead of it after Pierre’s unexpected death, and always refused to keep for herself the secret of Radium cooking –instead she got involved in the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation for the League of Nations…

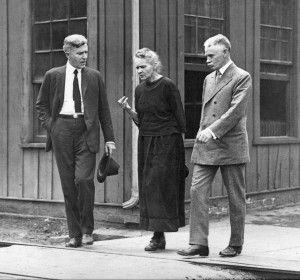

Marie Curie in 1921 during her tour to the United States in discussion with two fellow scientists in Pittsburgh.

Indeed, shared the Radium recipe of in her biography of Pierre Curie. In Chapter 4, she laid out the starting point: First, in order to get a consistent dough, you solve the urgent matter of taking care of home and the children –other ingredients and methods are mentioned in the following chapters, including how close collaboration and mutual acknowledgement leads to success and eventually a Nobel Prize, and further on, she brought out key details on technology transfer and her warm alliances with industry. But in contrast with the industrial framework, who took careful note of this recipe, other areas of society seem not to have incorporated what appears to be the first written account of conciliation.

Conciliation in the Curie story has been visited and revisited by academics working in gender and science issues for decades –recent accounts can be found in Susan Quinn (1995), Sarah Dry (2003), or Xavier Roqué (2011), which invite us to re-read Curie under this light. But in spite of all written evidence, somehow the conciliation message finds serious difficulties surfacing the big picture, that prefers to celebrate the superb intellect, the impossible feats, the isolated genius.

We can use these terms to define Marie Curie, for sure, but to understand her life, that is, to make some sense of it when reflecting from our own real perspective, we need to realize that scientific life, as any kind of life for that matter, either finds a way to integrate all our relevant selves, or it is not life.

We are celebrating Marie Curie’s life and legacy on her 150th birthday with a collection of blogs and free content around the theme of Women in STEM.

Check out our content Hub: Marie Curie at 150 – Celebrating Women in STEM

Latest Comments

Have your say!