The eighth post in the series The Horse in Human History

When Muslims invaded Iberia in the eighth century, they did not succeed in conquering the entire peninsula. In 718, Christian forces defeated the Arabs at Covadonga, where Goth Pelayo declared himself king of Asturias. Repulse of the Muslims at Poitiers in 733 allowed Asturias later to expand its frontiers to Lusitania, Galicia, Viscaya and in the ninth century to Leon. In the next few centuries Christian Spain would be a country divided by its mountains and provincial rivalries. One unifying feature of this tumultuous era, however, was the cathedral site of Santiago de Compostela, a sacred cult center. Minstrels plying the great pilgrimage routes to this shrine, in the wake of an important battle, would acclaim the heroic feats of great warriors. These ballads, elaborated poetically, became known as chansons de geste (songs of deeds). The finest of these epics was the Chanson de Roland, which recounted Charlemagne’s advance on Zaragoza in 778 and forced retreat back through the Pyrenees, where in a narrow gorge his rear cavalry was ambushed and heroically defended to the death by Roland of the Breton Marches. The Spanish national epic was El Cantar de Mio Cid (The Song of my Lord). This comparably embodied all the valor and anguish of the Reconquista and told how, unjustly banished by his king Alfonso, the champion El Cid indefatigably battled the Muslim invader, finally defeating the Almoravid colossus at the Battle of Cuarte in 1094.

Eager to benefit from the spoils of war against Islam, a steady influx of Christian warriors traveled from France and Burgundy. These warriors through exploits on the battlefield hoped to penetrate the knightly class. One sure route to social advancement though was through marriage into nobility. Thus to win the affections of a rare beauty, aspiring knights perforce resorted to the romantic songs and poems of courtly love. These recitals were enacted in the public forum of social gatherings, where performance was geared to the delicate taste and approval of noble society. Extolling the virtue of refined, adoring, and unrequited love, this tantalizing poetry spread from Spain across Provence to northern Europe.

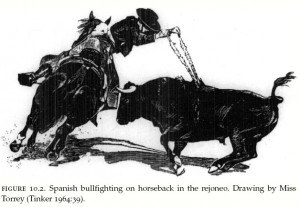

Central to success and renown was the knight’s equestrian prowess and nowhere were horse-riding skills more proudly displayed than in the chivalric bullfight. Over the centuries the rural capeas (fiestas in an enclosed space) featured the bull as a symbol of extraordinary sexual power and associated its potency with human fertility. Midst the hostility of the Castilian borderlands, these fertility rites became transformed into a knightly tournament before kings and aristocrats, in which horseman and toro bravo were antagonists and victory was won by inflicting death on the bull. Frontier epics portrayed the centuries-long contests between Christian and Moor as a chivalric Holy War, in which men achieved wealth and renown, “by fighting Moors and bulls.”

Central to success and renown was the knight’s equestrian prowess and nowhere were horse-riding skills more proudly displayed than in the chivalric bullfight. Over the centuries the rural capeas (fiestas in an enclosed space) featured the bull as a symbol of extraordinary sexual power and associated its potency with human fertility. Midst the hostility of the Castilian borderlands, these fertility rites became transformed into a knightly tournament before kings and aristocrats, in which horseman and toro bravo were antagonists and victory was won by inflicting death on the bull. Frontier epics portrayed the centuries-long contests between Christian and Moor as a chivalric Holy War, in which men achieved wealth and renown, “by fighting Moors and bulls.”

In the borderland struggle between the Christian north and Muslim south, different military religious orders emerged, among them the holy Order of Santiago. These warrior horsemen patrolled the lonely mesetas where no peasant dared settle for fear of Muslim raids. In time, the knights were instrumental in attracting Christian settlers to the freshly conquered territories. These monkish frontiersmen raised great herds in semi-wild fashion, migrating to the high sierras in summer. Their horses were the finest in Europe – part Arabian, part North African Barb, part Iberian stock, all of which combined courage and intelligence with dramatic beauty. Their method of open-range ranching, constantly involving the horse in periodic round-ups, branding, and overland drives, was unique to southern Iberia and soon would be introduced to the New World.

It was in this context of Reconquista that Christopher Columbus sought royal sponsorship for his projected voyage exploration across the Atlantic. Threatened on land and sea by the Ottoman stranglehold of the Near East and North Africa and her maritime access to the gold of Guinea blocked by enemy Portugal, Isabel of Castille, on the eve of Granada’s surrender, finally gave support to the Genoese’s plan to buscar el Orient por el Poniente (find the east via the west). On his first trip Columbus barely survived two hurricanes. But on his second he transported fifty horses to the New World. In time haciendas, courtly love poems, bullfights, and the dire Inquisition would reach the Americas. But first to arrive was the Spanish hidalgo, armed and armored in the finest steel, equipped with firearms, well trained in the military traditions of knighthood, toughened by the long bloody wars against the Moors, now flushed with final victory, and imbued with religious ardor for the new conquest ahead.

Reference: Tinker, Edward Larocque 1964 Centaurs of Many Lands. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Latest Comments

Have your say!