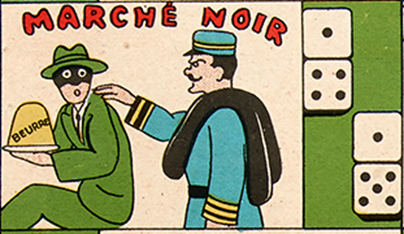

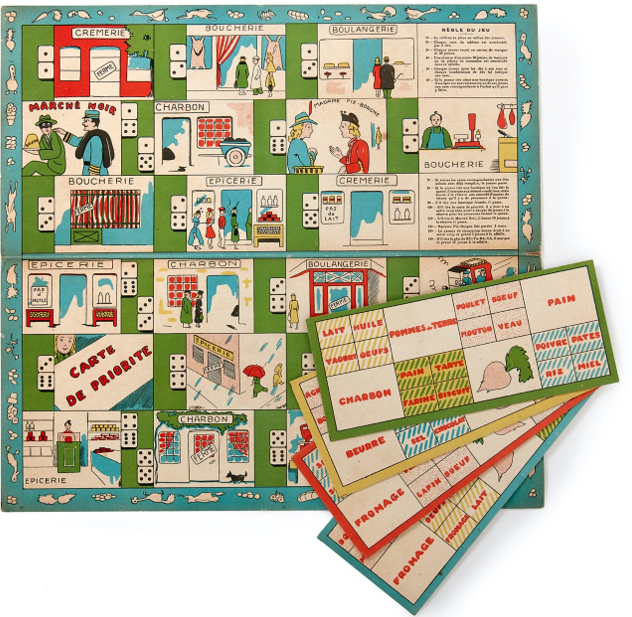

Food shortages were a fact of life throughout Europe during the Second World War, and a daily struggle for most consumers. In France a children’s board game, the “Jeu de rutabaga” (Rutabaga Game, 1942), replicated the adult frustrations in shopping for food. Players rolled two dice to determine which square they would go to, in trying to buy food from the shops on the board to obtain all the items on their individual shopping cards. Nearly half the shops are closed. At those with customers already waiting, players pay a one-token fine to the bank for each customer ahead of them in order to purchase food. If they land on “Madame Pie-Borgne” (Madame One-Eyed Magpie), they lose two turns in having to listen to her gossip. Landing on “Carte de priorité” allows immediate purchase with no fine, ahead of all the customers waiting, and then an extra turn. (In real life, these cards gave mothers priority for service when there was a queue, and were blamed for enabling card holders to make multiple purchases at shops for friends while the non-priority customers waited in the lengthy queues.) Landing on “Marché noir” incurs a 10-token fine.

The game highlighted the obstacles, and the time and patience required (on a vastly reduced scale), to obtain essential food supplies and coal. Wartime shortages and thestate controls to ration food and contain inflation created opportunities and incentives for producers, sellers and consumers to develop alternative paths for the supply of scarce goods. The black market thrived in all countries with food shortages and state economic controls. France offers a unique case for black-market study. The armistice in June 1940 allowed the formal existence of a French state, needed to administer the French economy, and providing potential to protect French citizens and resist German demands. But Vichy France’s choice to collaborate with German authorities compromised Vichy controls and encouraged the growth of the black market.

I became intrigued by the black market in France as a research challenge to determine its nature, scale, logic and consequences. Jacques Delarue, in a book based on his observations and records as a police inspector during the war (Trafics et crimes sous l’occupation, 1968), observed that of all the key terms during the war, “black market” was “without doubt the one that has remained engraved in most memories” of life under Occupation. In the most renowned depictions of the black market in the 1950s, in Jean Dutourd’s novel Au bon beurre (1952) and the Claude Autant-Lara film La traversée de Paris (1956), greedy and dishonest shopkeepers gain fabulous wealth from their black-market commerce. They exploit the vulnerability of helpless French consumers, while the police and state authorities appear as inept, negligent, and corrupt. Would archival and published sources tell a different story? How would they document the widespread illicit transactions that were organized to leave no trace? According to the Contrôle économique, the main state agency combatting the black market, “Its essential characteristic is to be very hard to pin down, it leaves no accounts and can only be proven in starting from very slight evidence.”

In fact, the archival evidence is substantial. Historians Paul Sanders (Histoire du marché noir, 1940-1946,2001) and Fabrice Grenard (La France du marché noir (1940-1949), 2008) have made impressive use of police, judicial and finance archives to explain the extraordinary growth of black-market activity in Occupied France. The state efforts to manage shortages, to “share sacrifice” with rationing, and to suppress “illicit increases” in prices, left records of state policy development, arrests, prosecutions, and the important changes in public opinion as state efforts floundered.

But as state documentation, these records present the black market as seen by the state. They are most thorough in providing a record of how inadequate and often inept the state efforts were. In my archival research, I became intrigued by the detailed accounting for implicit failure, even when claiming success. Authorities not directly engaged in the policing of markets, and thus with less at stake, gave more insightful assessment. As the Ministry of Finance tallies for the infractions climbed higher, department prefects and Bank of France directors described massive evasion of controls, beyond the capacity of enforcement officials. The black market earned some dealers, farmers and shopkeepers large fortunes, particularly those who sold to the Germans. But its extent and significance, during and after the war, can only be explained by the importance of the black market in the strategies for daily survival that developed at all levels of the economy: strategies to deal with the shortages, German exploitation, and the Vichy regime’s poorly designed controls. No one even thought of denouncing black-market activity, the Bank of France commented in 1944. It was too useful to everyone.

Just how pervasive the food shortages were, and the challenges of feeding a family in the system of unequally shared penury, is evident in the creation of games for children that made play out of the challenges facing their parents. In “Comme Maman”, children used ration tickets to obtain food that included the need to detect counterfeit tickets. In “Tickets S.V.P.”, players advanced around a board paying ration tickets to advance from shops, and receiving tickets at municipal offices, trying be the first to reach the “Dreamland with no tickets.” In the “Rutabaga Game”, it is noteworthy that the black market appeared as just one square on the game board. In fact, price and rationing infractions took place in the shops, and were rarely reported or recorded. Retailers, producers, and consumers with sufficient income had a common interest in evading controls. They adapted their behaviour to have it look as if they worked within the rules. Getting caught and fined for black-market infractions was an ever-present hazard, but a necessary risk in the very serious “game” of survival for ordinary consumers.

Latest Comments

Have your say!