Shortly after William Shakespeare’s famous words, “all the world’s a stage,” were uttered in the opening performance of As You Like It in the new Globe theater, the Red Dragon set sail to found the East India Company’s first factories. Coincidentally, the same ship, docked off the coast of Sierra Leone, was the site of the first recorded performance of Hamlet in 1607. As these early examples reveal, English theater has long mingled with, and been adjacent to, imperial pursuits. During the nineteenth century, Shakespeare’s plays enjoyed widespread popularity in both Indian classrooms and theaters. For Thomas Babington Macaulay and his like-minded predecessors, Indian theatergoers’ delight in Shakespeare was a source of pride. But the thriving theater scene of Victorian-era Calcutta was also famous for its biting political satire, which often set its sights on the colonial government.

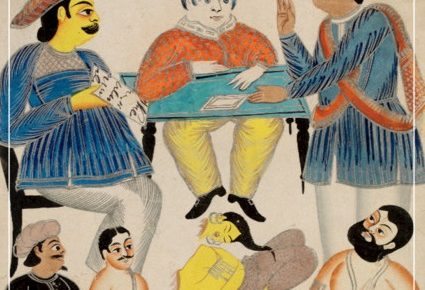

During the 1870s the dramatic arts flourished in Bengal, and lively theater performances provided an opportunity to enjoy literature as well as sociality. A spate of plays, including Dinabandhu Mitra’s Nil Darpan, which cast a spotlight on the exploitative practices of English indigo planters, Upendranath Das’s Surendra Binodini, Saratsarojini and Police of Pig and Sheep, which took aim at the conveniently-named police administrators, Commissioner Hogg and Superintendent Lamb, delighted Bengali audiences and inflamed nationalist sentiments against British rule. Such plays roiled English tempers, and in 1876 the police raided a performance of the National Theatre Company’s Gajadananda o Jubaraj, which satirized the Prince of Wales among others. In March of 1876 an interim ordinance placed a ban on “certain dramatic performances, which are scandalous, defamatory, seditious, obscene, or otherwise prejudicial to the public interest.” And by December, The Dramatic Performances Act was passed by the Governor General of India in Council, effectively extending a ban on political theater throughout the subcontinent. The Act clearly gestures toward the powerful interface between law and literature in the colonial world, a topic that I explore in my book Colonial Law in India and the Victorian Imagination.

The weight of the Act becomes even more significant when we think about it in relation to the historical and cultural events surrounding it. On New Year’s Day 1877, with a famine raging throughout the subcontinent that would eventually kill almost ten million people, the colonial government was staging a durbar in Delhi to proclaim queen Victoria Empress of India. In many ways, the Durbar was a theatrical event, and, as with the dramatic performances taking place on the stages of Calcutta, it was meant to serve a didactic purpose. While no less theatrical, however, the Durbar ostensibly depicted reality. Its effects were material, and the relational hierarchies it depicted were consequential. The remnants of the Indian aristocracy were summoned to publicly pledge their fealty to Queen Victoria, the newly-styled Empress of India.

The pageantry of the event was notable for its medieval aesthetics. Transposing a prior temporality onto the visual spectacle reflected a corresponding notion that India’s present was essentially England’s past, that traversing geographical distance amounted to travelling across time as well. The political theater staged in this event, and many others like it, performed an encounter between modernity in the form of rational British government, and the past, embodied in the native rulers watching from the sidelines. The suggestion of a developmental lag that this performance instantiates continues to resonate even into the present moment. Upendranath Das and his cohort of playwrights and directors working the stages of Bengal, however, might have had the last laugh. The Dramatic Performances Act sought to ban performances that were “likely to excite feelings of disaffection to the Government established by law in British India.” The Delhi Durbar turned out to be one such performance, as it fostered resentment rather than respect for the colonial government in many Indian observers.

Reading adjacently, as I do in pairing legal cases and literary texts both here and in Colonial Law in India and the Victorian Imagination allows us to open up lines of sight and avenues of thought that might not be apparent otherwise. Placing the legal/historical next to the literary reveals the turns of imagination at work in both the official narratives of law and in the cultural terrain.

Latest Comments

Have your say!