In late October 1841, the US slave trading ship Creole departed from Richmond, Virginia, transporting 139 captives bound for New Orleans, Louisiana. On November 9, nineteen rebels seized the ship and steered it toward Nassau in the Bahamas. The next four days witnessed diplomatic wrangling between the US consul and British colonial officials, military occupation of the vessel by West Indian troops, and the anchoring of hundreds of locals’ boats around the Creole in the harbor. After British officials declared they would not interfere if the captives decided to leave the slave ship, more than 130 of these former American slaves took the short walk to freedom. Shortly after, the Creole left for New Orleans with five captives on board, but minus its injured captain and a dead overseer. The former captives scattered across the Bahamas and Jamaica. This remarkable story has been told in bits but never fully narrated, documented, and carefully examined until now.

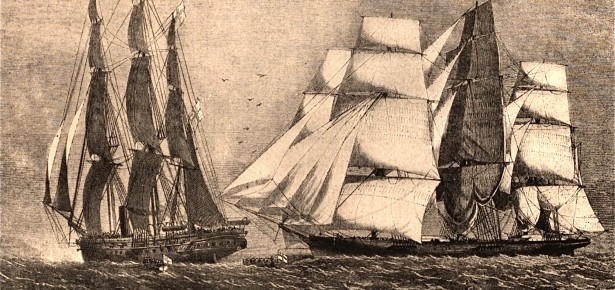

This maritime rebellion belongs to a larger history of slave trading in US coastal waters. The termination of American participation in the Atlantic slave trade in 1808 is usually seen as the end of seafaring commerce in black bodies followed by the continental expansion of the domestic slave trade. But this familiar scenario ignores the coastal dimensions of the slave trade across the young American republic. Captives continued to be transported on US merchant ships in large numbers for decades after the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade. More than 50,000 captives were moved from ports in the Upper to Lower South between the 1820s and 1850s. Hundreds of vessels like the Creole transported men, women, and children in numerous voyages. In the process, goods like tobacco from factories in the Upper South and finished manufactured products from northern factories spread commerce and developed new markets. Especially significant were the roles of owners, traders, insurers, captains, sailors, federal employees, and others in slave commerce adding to the expansion of the United States as a maritime empire. The rich historical scholarship on the internal slave trade has either overlooked or downplayed its seaborne features and their implications.

One important implication was the new proximity of slave and free coastlines. In April 1842, British Foreign Secretary Lord Aberdeen wrote to British special envoy Lord Ashburton. The peer had been sent to Washington DC to address difficulties in Anglo-American relations. The 1830s had seen the emergence of slave shores on one side and free shores on the other side. There had not been an issue when both shores were engaged in slavery. But now, after the passage of British colonial abolition and the expansion of US coastal slave trading during the 1830s, it had become a serious issue. Between 1830 and 1840, four US slave ships – the Comet, the Encomium, the Enterprise, and the Hermosa – had been driven into British ports and several hundred captives freed. The Creole revolt and stand off in Nassau harbor was a culmination rather than an aberration.

This issue of proximity is vital to the Creole story. The juxtaposition of slave and free shores, what slaves decided to do as a consequence, and the diplomatic crises that emerged, are some of the issues that attracted me to write this history. Indeed, I have been writing about slaves crossing borders in search of alternatives to slavery and the ramifications over the last decade and this book is the natural outgrowth. It might well determine what my future project will be. It is certainly germane with weekly headlines about desperate refugees crossing land and sea borders away from persecution and war in search of new lives, safety, and opportunities from Central America to the Mediterranean. Today’s newspaper reports the tragic deaths of twenty-eight Haitian migrants after their boat sank off the Bahamas.

A common view of the liberation of slaves from the Creole is that it was a British initiative. The British freed the slaves who ended up in their jurisdiction. This was certainly what American slave traders, slaveholders, and their political representatives argued. This attitude partly reflects a negative belief that slaves could never free themselves without outside interference. It ignores the collaborative roles of black pilot crews and members of the Second West India Regiment who guarded the ship. It overlooks the deliberate actions of local Nassau folks whose boats surrounded the ship preventing it from leaving with the captives. Most important, it ignores the American captives themselves who chose a short walk to freedom on foreign soil rather than stay put and voyage to their native land of slave soil.

One of the joys of being an historian is uncovering unknown pasts through archival research. Madison Washington is usually depicted as the leader of this slave ship revolt largely due to a sensationalist article about him published by the Liberator in early 1842. But research in the Nassau archives reveals fellow rebel leader Elijah Morris as a local, farmer and fisherman, household head, and man of property in Gambier village. His son Alexander inherited his father’s wealth and also purchased property. While digging through papers at the Amistad Research Collection in New Orleans, I found an insurance contract between John Hagan and the Ocean Insurance Company for nine captives being transported aboard the Creole. Nothing odd here, accept the contract was dated November 13, 1841 – the same time the nine men and women were now enjoying liberty in the Bahamas!

But Hagan the wealthy cotton factor, bank investor, and slave trader gets even more interesting. During the 1840s, he purchased Lucy Ann Cheatham. In 1856, he filed suit for the freedom of her and her two children Frederika and William. In his subsequent will, he bequeathed $10,000 and his residential property to Lucy’s children and $5,000 for their maintenance. After he died, Lucy lived in this palatial home and alternated between calling herself Cheatham and Hagan. Both the Morris and the Cheatham family went from being property to being propertied. Other research pearls I leave to the readers’ curiosity.

Let us return to the story’s richness. Today, issues of slavery, freedom, and commemoration are occupying space in popular culture in North America, Europe, the Caribbean, and elsewhere far more so than previously. In 1938, a journalist for the Baltimore Afro-American thought that the tale of the Creole would make a great movie. He might just be right!

Latest Comments

Have your say!