Academic writing tends to be very decorous. We are supposed to be objective, dispassionate, unruffled, speaking from the authority of our expertise. But perhaps all of that is a false mask, a professional lie that speaks anxiety as much as security, and ends up burying our own stake in what we are doing, or in the meanings we are trying to recover.

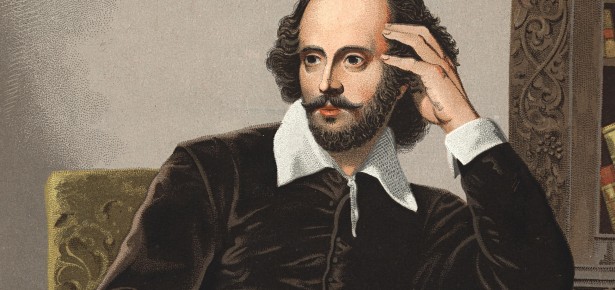

You have to risk things to discover things – including the risk of going too far, or the risk of bad taste – two things Shakespeare has long been known for, but which today’s scholars and practitioners tend to downplay in favour of a Shakespeare who can be familiar, accessible, and exemplary to all.

In Shakespeare’s Possible Worlds I intentionally try out different ways of thinking and writing – super-close readings, thought-experiments, philosophical speculations, even imagining actually being a theatrical instrument. I want the book to be a journey of discovery, with my own methods of transport visible – not a finished report from a point of arrival and completion. I hope readers will share the excitement of discovery.

Close reading is the key to a model of how Shakespeare – or how plays – can embody life

This means combining styles and methods that are often thought to be poles apart. For instance, close reading and critical theory. The two are to my mind intimately connected. To think ‘theoretically’ needn’t mean applying some or other continental thinker, or mapping the plays onto some preconceived system, or even using such a system to reveal the work. To my mind, the necessary theory emerges from the work itself. Indeed it is the work: playworlds have their very own bespoke physics and metaphysics, that only close attention to their movements can discover.

In other words, close reading is the key to a newly theorised model of how Shakespeare – or how plays – can embody life.

This is what I attempt in Shakespeare’s Possible Worlds. First, I identify a play-specific model of reality. Then I search for thinkers who might be able to speak to such possibilities. I do this partly to help supply a language for my own perceptions that is not exhausted by preconceptions; and partly to help articulate how the possibilities of playlife can speak to the possibilities of life itself. (What if playlife is truer than, or reveals the hidden matrices of, what we take to be life…?)

It is almost inevitable, I think, that the most inspiring thinkers here post-date Shakespeare – simply because Shakespeare’s playworlds so exceed the orthodox thinking and practice of his age. I find the most expressive model for playworlds in the dizzying ‘monadology’ of Gottfried Leibniz – the astonishing German polymath born 30 years after Shakespeare died. In Leibniz’s vision, the world pulses with infinite elastic nodes of life called ‘monads’: always changing, not bodies themselves but active in bodies, no two the same, each one of which expresses all of history from its own unique perspective, and each one of which is necessarily preformed. Creation itself works like an infinite network of metaphor. As I said, the vision is dizzying – but to my mind weirdly true. Just like Shakespeare.

For me, what I call Shakespeare’s ‘formactions’ – theatrical forms and instruments that express possible life – are like Leibniz’s monads. Every one of them is potentially alive, with its own appetite and perception. But you don’t need to know Leibniz to understand what I am trying to say. The principles in a sense are very simple. All things are alive; most things pass beneath or beyond our notice, but are nonetheless possible; our perceptions are overwhelmingly unconscious, so that we feel far more than we ever know. And as Leibniz himself puts it:

“It can even be said that by virtue of these minute perceptions the present is big with the future and burdened with the past , that all things harmonize, and that eyes as piercing as God’s could read in the lowliest substance the universe’s whole sequence of events.”

Might our eyes be as piercing as this? Perhaps not! But let us try.

Latest Comments

Have your say!