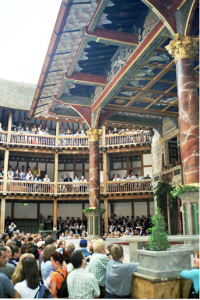

The reconstructed Globe marvelously evokes an earlier age, but visitors should keep in mind that its neighborhood is quite different from that of its Elizabethan namesake.

The district surrounding the original Globe fell in a “liberty,” land previously owned by a religious institution that was confiscated by the royal government during the Reformation. Although title to London’s liberties often found their way into secular hands, the crown granted to their new landlords the relative freedom from civic jurisdiction that church lands had enjoyed. The result was the appearance along the south bank of the Thames River a variety of popular pastimes that the City of London’s puritanical magistrates detested.

The district surrounding the original Globe fell in a “liberty,” land previously owned by a religious institution that was confiscated by the royal government during the Reformation. Although title to London’s liberties often found their way into secular hands, the crown granted to their new landlords the relative freedom from civic jurisdiction that church lands had enjoyed. The result was the appearance along the south bank of the Thames River a variety of popular pastimes that the City of London’s puritanical magistrates detested.

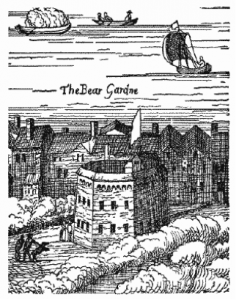

By the middle of the sixteenth century, the Bankside Bear Garden attracted crowds to watch bears and other wild animals tormented by dogs; Henry VIII witnessed the brutal spectacle in 1546. The area also had since the Middle Ages hosted brothels that were owned by successive bishops of Winchester, who regulated them and diverted their proceeds to charitable purposes, including nearby St. Thomas’s Hospital. Henry VIII closed the brothels toward the end of his reign, but they reappeared by 1600, around the same time as the Globe.

Municipal hostility explains why Elizabethan public theaters were established in London’s suburbs, outside the City’s jurisdiction, in the final third of the sixteenth century. At the time, preachers would rail against the profanity of theater. In 1577, Thomas White summarized their providential outlook succinctly in a sermon preached at Paul’s Cross, the great outdoor pulpit near St. Paul’s Cathedral in the heart of the City: “[T]he cause of plagues is sin, if you look to it well, and the cause of sin are plays, therefore the cause of plagues are plays.”

Renaissance London’s first public theater was the Red Lion, built east of the City in Whitechapel in 1567. In 1576 James Burbage established an open-air public playhouse called, appropriately enough, the Theatre in the north London suburb of Shoreditch. This was followed by the Curtain in the same neighborhood in 1577. In 1587 the open-air Rose (which is currently also the scene of archaeological work and potential reconstruction) was established across the Thames near the Bankside Bear Garden.

The riverside location must have been convenient: the Rose was followed by the Swan in 1596 and the Globe, built out of materials brought from the now defunct Shoreditch Theatre, in 1598. Although the Rose was the site for some of Shakespeare’s earliest productions, it found itself in the Globe’s shadow once Shakespeare moved there and for the next fourteen years wrote many of his best plays for the new stage.

The riverside location must have been convenient: the Rose was followed by the Swan in 1596 and the Globe, built out of materials brought from the now defunct Shoreditch Theatre, in 1598. Although the Rose was the site for some of Shakespeare’s earliest productions, it found itself in the Globe’s shadow once Shakespeare moved there and for the next fourteen years wrote many of his best plays for the new stage.

More reminiscent of inn courtyards and bear gardens, the open-air theaters were generally of three stories, their galleries roofed with thatch. One advantage to playing in the open air was that it was more conducive to the sort of spectacle the crowd loved: in 1613, during a performance of Henry VIII, the Globe’s thatch roof caught fire from the sort of special effect that was only possible outdoors, a firing cannon. Fortunately, the most serious injury was that of a man who found “his breeches on fire that would perhaps have broyled him if he had not with the benefit of a provident wit put it out with bottle ale.”

A second advantage to the outdoor theaters was their capacity: as many as 3,000 Londoners could come together in the afternoon to see the latest play, munch on apples and nuts, and drink bottle ale sold during the performance, idleness that generated the consternation of London’s preachers. The wealthy sat in upper boxes for 3 pence, the middling orders below them on benches for 2 pence, and ordinary people in the pit, the large open area on the ground level for a penny—hence their designation as “groundlings” or “penny stinkards.”

But would a pit dweller have noticed the “stinkard” nearby? Much would depend on the direction of the wind, for in Shakespeare’s London the Thames was an open sewer into which all manner of waste—human, animal, and industrial—washed with every rain. A visitor to the reconstructed Globe today may be forgiven for a sense of nostalgia for the sights and sounds of the original Renaissance stage, but some aspects of the experience are surely best left in the Age of Elizabeth.

But would a pit dweller have noticed the “stinkard” nearby? Much would depend on the direction of the wind, for in Shakespeare’s London the Thames was an open sewer into which all manner of waste—human, animal, and industrial—washed with every rain. A visitor to the reconstructed Globe today may be forgiven for a sense of nostalgia for the sights and sounds of the original Renaissance stage, but some aspects of the experience are surely best left in the Age of Elizabeth.

Latest Comments

Have your say!