I grab for my gas-mask…Gaaas-Gaaas- I call…my helmet falls to one side, it slips over my face…I wipe the goggles of my mask clear of the moist breath…These first minutes with the mask decide between life and death: is it tightly woven? I remember the awful sights in the hospital: the gas patients who in day-long suffocation cough their burnt lungs up in clots. Cautiously, the mouth applied to the valve, I breathe.

In the above lines from All Quiet on the Western Front, the renowned German war novelist Erich Maria Remarque introduced his readers to gas attacks in the western trenches of World War I. And while poison gas was just one of several new weapons that Remarque described in order to convey the brutality of modern trench warfare, his gas scenes maintained enough salience to make it into in each of the three subsequent films based on the novel (1930, 1979, and 2022).

All three of the All Quiet on the Western Front films attempted to convey gas attacks with the narrative methods that Remarque first employed. Upon presumably sensing the gas, either via sight or smell, the soldiers begin to scream and panic, thus trying to bring the reader or viewer into a complete sense of disorientation. After the first screams of alarm wash over, the soldiers begin to react, pulling out gas masks and placing them on their faces. Smoke then clouds the viewer and the soundtrack shifts to an uncanny silence, punctuated by the sound of heavy breathing and racing heart beats.

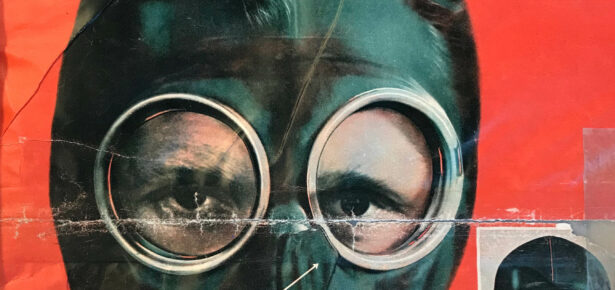

With these methods, the films attempt to depict a weapon that tends to defy narrative conventions. The ephemeral nature of poison gas certainly makes it difficult to visualize. While yellow-green smoke may approximate certain World War I gases like chlorine, others like phosgene were nearly invisible to the naked eye. For this reason, the gas mask serves as the more important physical representation of the attack, conveying not only the presence of gas but also the strange and dangerous technological world that the men now inhabit. Furthermore, the experience of a World War I poison gas attack was not solely defined by the moment of alarm. Listening to the soldiers stertorous breathing and heightened pulse helps communicate to the audience that the soldiers must now live and fight in an environment that weaponizes breathing, one of the most basic elements of human survival.

It was the sense of unknown duration, in tandem with its invisibility and creeping movement, that made poison gas one of the most feared weapons in World War I. This fact is quite striking given that gas produced less than 1% of the war’s total causalities. Furthermore, gas was not a tactically effective weapon until the last year of the war and a large percentage of soldiers, across the diverse global theaters of the war, never encountered the gas soaked trenches of 1918.

This percentage increases, however, for the Germans, who directed many of their remaining men and resources to the Western Front in the final official year of the war. It was these men who would later claim that poison gas best symbolized the mechanized fighting of World War I because it removed any sense of individual human agency on the battlefield; survival was a mere matter of chance and protective technologies like the gas mask, as Remarque’s quote reveals, always maintained the possibility for lethal error. These feelings would therefore help to explain why poison gas and the gas mask were such important technologies in German attempts to retell and understand the war. Remarque’s novel, the best-selling in its genre, was the most remembered work amidst hundreds of novels, plays, poems, songs, films, and pieces of visual art that grappled with the war’s meaning in the late 1920s.

A fellow German army veteran and contemporary of Remarque, Ernst Jünger similarly suffused his interwar novels and nonfiction writings with poison gas and the gas mask. But while Remarque’s work gazed paralyzed in horror at the violence that such weapons produced, Jünger advocated for an active interwar engagement with what he saw as the arms of the future. If the Germans were to survive what many envisioned as a fated second war, then they would need to effectively utilize modern technologies like the tank, airplane, poison gas, and the gas mask. Indeed, as part of this process, Jünger postulated that the face of the modern German would increasingly come to resemble the emotionless gas mask as soldiers and civilians alike steeled themselves for future aerial attacks.

While German interwar intellectuals produced plenty more imaginative engagements with the technologies of chemical warfare, questions surrounding future violence were not merely academic. A loose group of technical specialists, often maintaining professional or military ties to the German chemical weapons program in World War I, began to offer their knowledge to the German state and its people. Alongside a thorough cultural survey of poison gas and the gas mask in the interwar imagination, The Gas Mask in Interwar Germany: Visions of Chemical Modernity follows these self-styled “gas specialists” as they made chemical weapons a pressing political, technical, and existential matter for the German nation in the 1930s.

When the Nazis rose to power in 1933 many of the gas specialists accommodated or allied their work to the National Socialist state, recognizing that the Nazis would afford greater political importance to aero-chemical protection and lend greater credence to the idea that Germany was surrounded by looming aero-chemical threats. The ideas of the gas specialists were now carried out and tested, as the Reichsluftschutzbund (or Reich Air Protection League), drilled the German public in air protection exercises like donning gas masks and evacuating to shelters. The gas specialists’ technical influence on these measures peaked in the mid-1930s and then waned as Nazi officials began to recognize that the gas mask was more valuable as a means of ideological indoctrination than as a mere tool of civil defense. In developing a mass-produced gas mask and making it mandatory for all Germans to own one and drill with it, the Reichsluftschutzbund attempted to forge Ernst Jünger’s vision of a technologically fortified populace ready for future aero-chemical warfare.

But in the war that did come, German civilians were not gassed and they developed ambivalent relationships to a technology that now had little apparent value. When compared to the passage from Erich Maria Remarque, a young girl’s dairy entry from 1945 Dresden demonstrated even greater suspicion of the gas mask’s claims to protection against an unseen and unknown danger. She wrote: Quiet horror oozes from the gas masks nearby. Their handling had to be practiced regularly; they were drawn like bathing caps taut over the face, creating a feeling of suffocation and filling the nose with a penetrating rubber odor. The eyes sitting behind the glass eye pieces and the snout-like ventilation filter make people appear like monstrosities from another world. We sat together silently because we could not speak, listening anxiously to the dull drones of the bomber squadrons above our heads, destined to drop their deadly load on German cities.

By intruding on their daily lives with its rubberized odor and digging straps, the gas mask did indeed begin to at least visually forge a new and exclusionary national community of militarized Germans. At the same time, however, it also insisted on a new conception of the surrounding atmosphere that was filled with imminent danger. In this way, poison gas and the gas mask prefigured relationships to environmental risk and mastery that proliferated in the Atomic Age. But beyond the great amount of existential anxiety that this produced in the interwar period, what were the social costs? The Gas Mask in Interwar Germany takes readers through the grand offers and disastrous failures of poison gas protection as the German nation sought to recast the modern world in its favor.

Latest Comments

Have your say!