For one of the first of the over 250 drawings that Rockwell Kent made to illustrate Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) in 1930, he propped Ishmael up on his elbows, lying on his belly on a grassy hill. This is the famous opening scene of the novel, in which Melville’s narrator says: “Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodically knocking people’s hats off – then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball.”[i] Ishmael is desperate. His only solution is an abrupt departure and time at sea. In Kent’s rendering, Ishmael’s whole body is tensed towards the view before him: of a wide expanse of ocean, so close that the sea breeze runs through his hair. Unseen but no doubt before him is a cliff tumbling down to the water, so that he and it are separated by a fall. It is an image whose relief can only be found outside of itself.

Like Ishmael, Kent had a near-compulsive desire to find himself in the outdoors. The opening to Kent’s Voyaging, his 1924 account of traveling by boat to the edge of South America, bears remarkable similarities to Moby Dick: “Here in this happiness the heart cries out its own despair, speaks its own doom and banishment. How unobserved and silently is the deep measure of the soul’s endurance filled; it mounts the rim, trembles a moment there, then like a torrent overflows – the vast relief of action.”[ii] Kent acted quickly. Within an hour, he had secured a berth on a boat to South America bound for the strait of Magellan.[iii] Both he and Ishmael had to depart. And that is really what his illustration set for Moby Dick is: a story of a departure.

In my book The Art of the Reprint, out this month with Cambridge University Press, I write about four twentieth-century artists’ encounters with nineteenth-century novels. I describe how Kent, an American painter, illustrator, adventurer, carpenter, and socialist more likely to credit lobster fishermen as inspiration than a contemporary like Edward Hopper, came to illustrate Moby Dick in drawings painstakingly inked to imitate the gloss of wood engravings; and also how in 1929 the British wood engraver Clare Leighton moved to Dorset to illustrate Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native (1878) near the place where its author had created it; and how in 1943 the German Jewish artist Fritz Eichenberg illustrated Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847) after having fled Nazi Germany for America, without ever having read the Brontës or been to Britain; and how between 1957 and 1975 British master engraver Joan Hassall created tiny, detailed, and anachronistically styled prints of the Georgian social world for a set of The Complete Novels of Jane Austen. In each instance I am interested in the unusual affinities that these artists had with these novels – in how they found themselves in these books, as Kent did with Moby Dick.

Kent, Leighton, Eichenberg, and Hassall, took voyages real and imagined to Melville’s oceans, Hardy’s heaths, Emily and Charlotte Brontë’s moors, and Austen’s drawing rooms, and also transported those authors’ books forward, to new landscapes and contexts. In so deftly combining and re-combining text against image against personal experience, they provided an invitation to their readers to do the same. While they were far from the only illustrators to take up the nineteenth-century novel in the twentieth century, they did so with particular attention to the gap of time between their subjects and their images, and with an especially rich approach to the material possibilities of wood, paper, and ink. Mediators between text and book and author and reader, these artists interpreted these novels and then illustrated their interpretations, stunningly and strangely. Theirs is the art of the reprint.

One principal tenet of my book is that artist-readers act upon books, changing them. Another is that books act upon illustrations, shifting their meanings. Moby Dick – and really any novel, and certainly all the novels I look at – is highly responsive to being illustrated. Visual or pictorial elements in literature may be highlighted by illustrators, but they may also speak a kind of theory of seeing back to the illustrations. Ishmael instructs Kent in the proper depiction of whales and Jane Eyre teaches Eichenberg how to read. Hardy’s bursting heath lives next to Leighton’s flora and fauna and Austen’s lightly drawn landscapes next to Hassall’s sweeping hills. J. Hillis Miller said of a Charles Dickens novel and its illustrations that “Each illustrates the other, in a continual back and forth.”[iv] Miller was describing the close one-on-one collaboration that Dickens and George Cruikshank maintained over several years and several book projects. Such a contemporaneous relationship was not available for Leighton, Kent, Eichenberg, and Hassall to have with Hardy, Melville, the Brontës, or Austen. These artists participated in Miller’s back and forth but also in something else, something more temporal and more personal.

Take Kent, for example. In a letter, his editor suggested that he might treat his Moby Dick illustrations like a diary: “If from day to day you are keeping a diary and you illustrate it with sketches to supplement your text, sometimes they come in as little incidents in squares – other times they are vignettes – and other times they occupy half or full pages. A nice intimacy is established between text and pictures. There is a beautiful fusion of word and diagram, making a variable harmony which becomes very delightful.”[v] Kent designed and illustrated Moby Dick as if it was not just a story but in fact the story of his life. Informal and spontaneous, incidental and ever-changing, his pictures fused with the language of the novel. Michel de Certeau said that “the story of man’s travels through his own texts remains in large measure unknown.”[vi] Kent’s illustrations are precisely the story of his travel through text, ocean, and life. Kent, like Melville, knew the sea, and depicted it to dazzling results. Also like Melville, he had an eye for the metaphysical and was willing to obsess over the habits of whales and whalers. Taken together, his drawings for the novel are an obsessive, imaginative, and energetic diary in images and a beguiling odyssey into the sublime. Years later, in 1955, Kent would take a case to the Supreme Court to fight for the right to travel regardless of his political beliefs. During the proceedings, his memoir, which was in part illustrated with images from his Moby Dick, was used against him. When he won his case (in a decision that allowed he and thousands of others to travel, including Paul Robeson) those images stood as a kind of defense of the right to wander. In a very Melville-ian way, Moby Dick was Kent’s memoir and his memoir was Moby Dick.

Every era remakes its books. Lewis Mumford famously announced that “Each man will read into Moby-Dick the drama of his own experience and that of his contemporaries…Each age, one may predict, will find its own symbols in Moby-Dick.”[vii] Kent, Leighton, Eichenberg, and Hassall indelibly transformed their novels by reading through place, person, era, geography, and biography. They illustrated with the kind of hindsight that Simon Dentith has defined as memory at its most “active and diligent, engaged in what can seem like a ceaseless task: the effort to come to terms with, to make sense of one’s own past.”[viii] They were coming to terms with the characterizations, narratives, perspectives, and landscapes of a past literature through the lenses of their own experiences. As a result, Moby Dick became a twentieth-century adventure saga, The Return of the Native a parable of lost landscape, Jane Eyre an anti-fascist treatise on individualism, and Jane Austen’s novels theses on how to bring the past into the present through intense attention to detail.

Because the books that resulted from Kent, Leighton, Eichenberg, and Hassall’s illustration projects are now doubly nostalgic residents of our home libraries – they were always metonyms for the nineteenth century and now they are also stand-ins for a particular moment in the twentieth century – they might easily face us backwards, to old stories, beloved characters, and remembered circumstances. And yet, stripping away all the complex dynamics of authors, publishers, artists, and readers that I have here endeavored to elucidate into linear timelines, there is a powerful present-ness to these books. Walter Benjamin described the image as follows: “It is not that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation.”[ix] To un-shelve one of these books and read its images against its text is to navigate a spontaneous constellation of word, image, story, character, and experience. It is even, perhaps, to be suddenly stilled, and to find that a novel from the nineteenth century inside of a book from the twentieth century can be a doubled mirror – you in it, it in you.

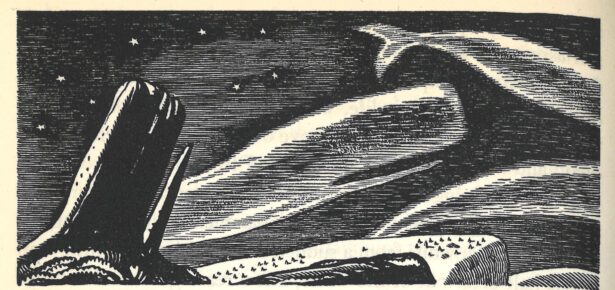

Masthead image by Rockwell Kent, “Of Whales in Paint; in Teeth; in Wood, in Sheet-Iron; In Stone; in Mountains; In Stars,” from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick: Or, the Whale (1851). New York: Random House, 1930. Image rights courtesy of Plattsburgh State Art Museum, State University of New York, USA, Rockwell Kent Collection, Bequest of Sally Kent Gorton. All rights reserved.

[i] Herman Melville, Moby Dick: Or, the Whale, illust. by Rockwell Kent (New York: Random House, 1930), 1.

[ii] Rockwell Kent, Voyaging: Southward from the Strait of Magellan (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1924), 2.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] J. Hillis Miller, Victorian Subjects (Durham: Duke University Press: 1991),153.

[v] Letter from William Kittredge to Rockwell Kent, July 27, 1928, Rockwell Kent Papers, 1935-1961, Archives of American Art. Smithsonian Institute. Washington, DC, Reel 5174, Frame 1115.

[vi] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans.Steven F. Rendall (1980; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011), 170.

[vii] Lewis Mumford, Herman Melville (New York: Literary Guild of America, 1929), 194.

[viii] Simon Dentith, Nineteenth-Century British Literature Then and Now: Reading with Hindsight, (Farnham, Surrey; Burlington, VT: Routledge, 2016), 1.

[ix] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2002), 462-463.

Latest Comments

Have your say!