Medieval manuscripts are striking for their material properties. Comparing the cold screens of word processors, the animal skin—parchment—which books were written on is weirdly organic, even gross. In an age with no publishers or ‘house style’, scribes could reinvent books to fit format to textual form in freakish ways. The hard work of copying Chaucer’s poems (say) by hand makes your arm ache just to think of it. It is no wonder that students of medieval literature are taught—indeed, taught in classes by me—to think of it as a ‘material text’. It truly was.

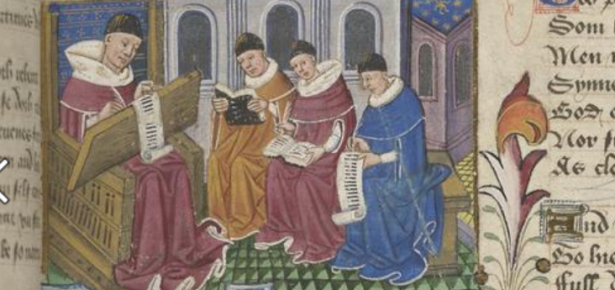

It wasn’t only that. Craftspeople were influenced by complex ideas and, in crafting books, by ideas about literature—immaterial texts, if you will. Recent writers—such as the woodworkers-turned-philosophers David Pye or Arthur Lochmann—have captured the concepts which inform craft now. In Immaterial Texts I reconstruct them for the makers of books in late medieval England from the archaeological evidence of the books themselves. These craftspeople, teasingly, seldom wrote their thinking down; it’s immaterial in this sense too.

Consider the parchment. There are powerful pages where writing about skin is all the more vivid because it is written on skin, but most of the time scribes cover the blemishes and damage that remind us what these grisly pages are made of. They are more interested in writing perfect rectangles—which still dominate western design for books. This immaterial idea drives the scribes alongside the duress of the real materials.

Another chapter notes how page breaks interrupt the reading of long works. Medieval scribes sometimes seemed annoyed by that and added cues to help people read fluently when they turned the page. One reader noted that a rude joke in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales was interrupted by the break between pages: ‘verte folium’, he urged in Latin, or ‘turn the leaf!’ People seemed more interested in reading words aloud or in the mind than in the page as physical format.

The last chapter focuses on the process of copying words. That’s not something that studies of ‘material texts’ always address, but words are also, strictly speaking, ‘materials’: ink on parchment or paper, produced by the hard labour of handwriting (which medieval scribes do moan about). But in copying the words there is a paradox: you make one material book, but that book gets its value only from echoing another book, an immaterial link from object to object. It is like the perfect rectangle in design: an aspiration to something abstract, conceptual, that inspires the making of a material thing.

To recognize those ideas helps us remember that the scribes who made English literature were thinkers. Their craft was underpinned by immaterial concepts, including concepts of the text as immaterial, as well as by their other, more material concerns. Recovering the scribes’ unwritten ideas is one thing I hoped to do by writing Immaterial Texts.

Watch a recent talk on the book here:

Latest Comments

Have your say!