For all its other-worldly reputation, philosophy has always been very good at PR. Already in ancient Greece, philosophers sold their teaching as a way of life that would supposedly make you a better, happier person. One member of the Epicurean sect erected a giant billboard in Oenoanda (South-West Turkey), telling its citizens that adherence to Epicurus’s philosophy would bring them ‘salvation’ from anxiety. But perhaps no time or place has been more celebrated for the supposedly emancipatory potential of philosophising than early modern Europe. For centuries, philosophers such as René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz have been heralded as the heroes who dragged Europe out of scholastic darkness into the light of the ‘Age of Reason’.

It therefore comes as a surprise to find that educated men and women of the early modern period itself felt very differently. In fact, by 1700 few things were more often reviled than speculative forms of philosophising. Even basic textbooks for university students complained about the damage done to the shape of knowledge by excessive philosophising; instead, they advocated new, non-philosophical methods of acquiring learning. Given that less than two centuries earlier systematic philosophising had stood at the heart of the European system of knowledge, this was a remarkable transformation. How did it occur?

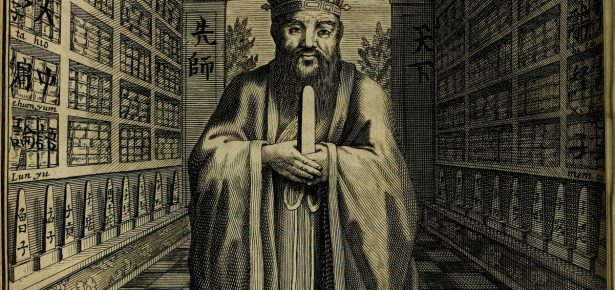

My Kingdom of Darkness attempts to answer this question. It takes its title from Book IV of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651), in which Hobbes railed against ‘that painted and garrulous whore who has for a long time now been taken for philosophy’. But my focus is not on Hobbes, but on structural changes within the pan-European system of knowledge: at universities, academies, courts, churches, and in the missions that European clerics undertook across the globe. I chart how those studying the natural world—above all medical physicians and mathematicians—increasingly redefined the ends of natural philosophy to exclude anything that looked like metaphysics. Their critique found an ally among an unexpected group: theologians. Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, professional theologians—both Catholic and Protestant—increasingly suggested that divinity should be a philological rather than a philosophical enterprise; in doing so, they significantly eroded philosophy’s importance to the structure of knowledge. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, European scholars and travellers developed what I call a ‘critique of pure reason avant la lettre’. Using new evidence from across the world, and especially from Asia, many of them came to believe that when left to its own devices, the most coherent metaphysical system that human reason could achieve was a terrifying atheistic monism. This, they suggested, was the system historically adhered to by élites from ancient Egypt and Greece to modern India and Japan. It was to be avoided at all costs.

In turn, I show how this intellectual background allows us to reconsider the thought of perhaps the two most famous thinkers of the period around 1700: the Huguenot scholar-journalist Pierre Bayle, and the English mathematician-natural philosopher Isaac Newton. Both have been the subject of great debate. In Bayle’s case, historians have even spoken of an unsolvable ‘Bayle Enigma’ (was he an atheist or a devout Christian?). And the fundamental patterns of thought behind Newton’s discovery of universal gravitation remain as contested as ever. Drawing on everything that Bayle and Newton wrote—and much of what they read—I show that like Hobbes, they both had conceptions of a Kingdom of Darkness in which speculative philosophising, both European and Asian, played the central role. For Bayle, removing the influence of philosophy on religion would lead to the end of theological strife and religious persecution, while at the same time buttressing the true, Protestant faith. For Newton, removing every vestige of metaphysics from natural philosophy would open the door to a superior mathematical physics, and to a better theology. These two remarkable thinkers, never previously considered together, were therefore part of the same momentous movement in European intellectual life. Philosophy, no less than any other sphere of human activity, has a socio-cultural history that must be told alongside the history of ideas.

Dmitri Levitin, The Kingdom of Darkness: Bayle, Newton, and the Emancipation of the European Mind from Philosophy (900pp) is out in March.

Latest Comments

Have your say!