I have the great honor of inaugurating a new series on World Literature at Cambridge University Press. Long, long ago, before I ever dreamed of writing such a book, I was introduced to the debates on world literature through Susan Sontag’s 2005 essay “The World as India.” At the time, I was very much not an expert on Indian literature. But no matter—neither was Sontag! Still, for her, India was a productive place to think through the problem of “world literature,” being both an exemplary multilingual location and subject to historical, geopolitical, and economic vulnerability to English. Indeed, for modern scholars, India has become the imaginative battleground for a winner-take-all contest between multilingual World Literature and what we now call Global Anglophone literature.

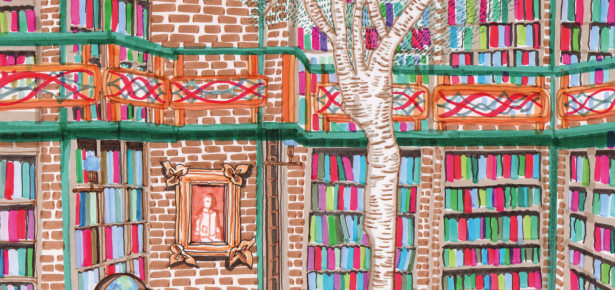

This polemic has been with us for a long time. In fact, it goes all the way back to the “Macaulay Minute,” the document most often cited to describe the role of English language (and literary) education in the epistemological violence of British colonization. In it, among many other infamous quips, Macaulay states that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India.”

Versions of this challenge have haunted South Asian literature ever since. After the rupture of colonization, there is no going back to a pure version of “native literature of India,” Macaulay so easily brushes aside. But nor can one unproblematically bury oneself in the “European library” Macaulay endorses. Instead, as I show, South Asian authors navigated toward a third option. They invented a countershelf.

What I call the countershelf is a collection of texts, authors, and locations of World Literature through which writers in the Global South identify against the Anglophone globe in which they are simultaneously compelled to circulate. I show how Indian and Pakistani Anglophone authors rose to prominence as exemplars of “Global English” precisely by refusing English—instead drawing from, debating with, and ultimately contributing to a concept of World Literature centered on writing from Latin America. Central to the concept of a countershelf is an author’s active choice to affiliate to another part of the world, the dynamic range of meanings that can be ascribed to that choice, and the ability of one participant to disagree with others about what fits on the shelf and how to interpret it. This enduring discourse of affiliation and resistance that helped many differently situated authors negotiate their own positions within the tradition of South Asian literature and the larger field of World Literature.

Let me give you a couple examples of how this form operates from the work of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, a leading Indian Anglophone poet of the 1960s and 1970s. In 1969, Mehrotra wrote breathlessly to his friend and fellow poet Adil Jussawalla:

Have done another mukhbodh poem and sent it to Mundus Artium. […] Their recent Latin American fiction number is tremendous. Also Paz’s great long poem Sun Stones in a Texas Quarterly. Will bring along a copy of it for you. Again my heart’s theory, we’re part of Latin America and Africa emotionally, and their literature is the one from which we ought to learn (Mehrotra 1969).

In a later poem, “Borges,” Mehrotra clarifies how the inheritance of the countershelf operates in his own writing:

A borrowed voice sets the true one

Free: lead me who am no more

Than De Quincy’s Malay, a speechless shadow in a world

Of sound, to the labyrinth of the earthly

Library, perfect me in your work (Mehrotra 1998, 3)

In this poem, Mehrotra literally invokes the library (Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel” as well as his own work as a librarian) and asks Borges for a “borrowed” voice that leads to his “true one,” a gesture that can effectively counter the silencing of Asian subjects – “De Quincy’s Malay” – in British Orientalist fantasy. He is saying, in effect, you think I come out of De Quincy, but I claim Borges as my progenitor instead.

For Mehrotra, Borges can also act as a model for the critical apparatus around South Asian Anglophone literature. “The example of Borges is enough to show that the Indian English poem needs to be read in a radically different way: not as a delectable slice of reality which the critic […] applies his nose, but as a place, a construct, housing two or more ways of seeing” (Mehrotra 2014, 170–171). For Mehrotra, the fact that Latin American literature was able to circulate as an aesthetic innovator – a “way of seeing,” rather than a merely sociological “slice of reality” – paves the way for his own writing to undergo a similar shift in reception as it circulated in beyond India into the World. In this book, Mehrotra forms part of a cohort of South Asian writers who found, through Latin American literature, a way to write in English on their own terms.

References

Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. 1969. “Note to Adil Jussawalla,” n.d. (likely 1969). Box 3, folder 7. Cornell University Bombay Poets Archive. https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/RMM08519.html#s2.

———. 1998. The Transfiguring Places: Poems. Delhi: Ravi Dayal Publisher.

———. 2014. Partial Recall: Essays on Literature and Literary History. New Delhi: Permanent Black.

Latest Comments

Have your say!