It is entirely reasonable to believe that media coverage is systematically flawed. In some ways, it is! Too much attention is paid to violent crime (Altheide 1997; Soroka 2014). Tweets are increasingly presented as representative public opinion (McGregor 2019). Changes in media technology have facilitated, and quite possibly enhanced, political polarization in media sources and political beliefs (Bail et al. 2018).

Even as media coverage is imperfect, there are reasons to suspect that media partly fulfill their function in modern representative democracy. A large volume of research confirms that media coverage provides a reasonable (if imperfect) representation of the national economy, for instance. Media reporting during campaigns tends to rise and fall with campaign events and public support for candidates itself. And the news tends to following the ebb and flow of policy over time.

Evidence of accurate media coverage, and public responsiveness to that coverage, is of real significance. Government accountability depends on informed citizens. So too does political representation. Why, after all, would we expect governments to represent public preferences if those preferences weren’t at least minimally informed? Effective representative democracy depends at least in part on accurate media coverage of legislative action and policy change.

A critical task for scholars of media and democracy, then, is to identity areas in which media fail or succeed. The recent literatures on misinformation and disinformation have (appropriately) focused a good of attention on failures (e.g., Lazer et al. 2018). Our own work identifies some failures as well. News coverage in the US does not neatly reflect federal spending policy in certain important areas, such as education and the environment. But news does reflect what is happening in other significant domains, including defense, welfare, and health.

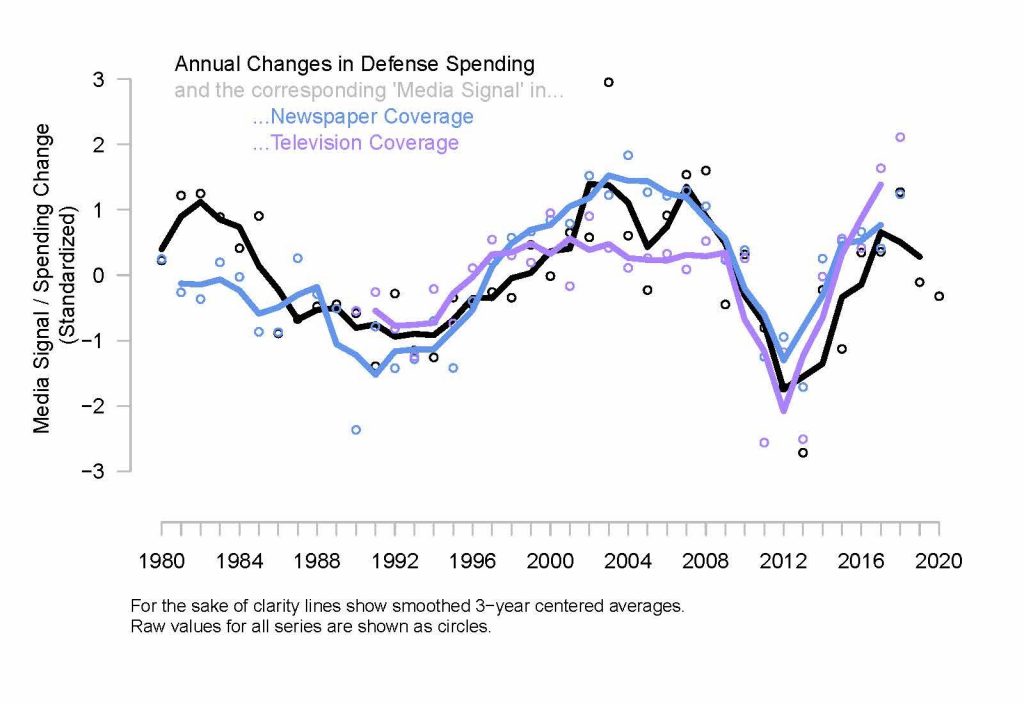

Consider for instance the graph below, which compares media coverage of defense spending change and actual changes in defense spending over nearly 40 years. The spending data shown here are relatively straightforward: these are changes, from one fiscal year to the next, in total dollars spent by the US federal government on defense, as reported by the Office of Management and Budget. We show a standardized measure in order to plot spending change alongside the “media policy signal.”

What is that “media policy signal”? We begin by extracting every sentence about defense spending from major US newspapers and television networks. (Details of our methodology are available here.) Using computer-automated text analysis, we identify sentences that suggest upward or downward changes in spending. We then combine these sentences each fiscal year to produce a “signal” – an indication of what readers could learn about spending change if they were attentive to media coverage.

Our results suggest a strong correlation between media coverage of spending and actual spending change on defense. Indeed, even when we look at different media outlets separately, most produce coverage that is roughly in line with what policy is actually doing. This is good news for media, and good news for democracy. If Americans want to learn (and act upon) information about what their government is spending on defense, media are providing at least some of the necessary information. Defense is one of several domains in which media coverage of policy is fairly accurate, which also include spending on welfare and health. Importantly, these are ones where past work finds evidence that Americans respond to policy change.

This rosy picture does not carry over to all policy domains. As noted earlier, media coverage is much less reflective of changes in spending on education and the environment. (Results are available here.) While our data indicate that media coverage often provides an accurate depiction of changes in spending, then, coverage is not perfect – and this is true even in the domains where it does reflect government actions. This may come as little surprise to most news consumers; what may surprise is that coverage often is quite accurate in certain salient areas – defense, welfare and health. It just is not as bad as you might think.

We take these results as a useful reminder of the importance of the media in democracy. Accurate coverage of government actions makes possible political accountability on Election Day. It also makes possible the effective guidance of elected officials in between elections. Identifying the successes and failures in US media coverage is fundamental for those interested in informative, accurate journalism to be sure. But it also is critical for anyone who values effective representative democracy.

Latest Comments

Have your say!