There’s a movement to diversify the British literary canon and a crucial step may be right in front of us. Allow me to explain.

The British Romantic period—broadly conceived as the 1780s through the early 1830s—was once admired for its religious aspects. Some credited the literature of the period with inspiring an Anglo-Catholic revival in the mid-nineteenth-century Church of England. Over the course of the twentieth century, however, other scholars countered this idea, emphasizing the ways Romantics secularized traditional beliefs about nature and human personhood.

In his groundbreaking work, Natural Supernaturalism: Tradition and Revolution in Romantic Literature (1971), M. H. Abrams asserted that British Romantics assimilated Christian theological ideas in new forms. Among his most striking interpretations was a reading of Wordsworth’s poetry that denied the presence of God in any meaningful way. Imagine the disenchantment many of Wordsworth’s nineteenth-century devotees would have felt!

Abrams wasn’t alone in this. His scholarship reflected a wider conversation about literature and religion that spanned the disciplines and announced the “death of God” in the maturation of Western society. In this view, the preoccupation with faith and doubt among the Victorians was the flowering of secularizing seeds planted decades earlier. In short, the Romantics ushered in the modern demise of religion.

The recent publication of The Cambridge Companion to British Romanticism and Religion reflects what some call a ‘postsecular’ understanding of Romantic literature. The authors, though not all of the same mindset, demonstrate that the relationship between Romanticism and religion is far more complicated than many nineteenth- and twentieth-century readers grasped. Indeed, as the Companion reveals, Romantic religiosity extends far beyond Christianity.

The Church of England remained a significant religious influence during the period, but patterns of political dissent and Roman Catholic immigration reveal diverse networks of collaboration, esoteric spirituality, and burgeoning print culture that could easily be overlooked in favor of the Establishment. Islam and Hinduism contributed to British culture too, as members of less visible religious communities engaged in trade, political activity, and linguistic exchanges. Vibrant Jewish intellectual circles, part of a growing population numbering in the tens of thousands, expanded in and around London during the period as well.

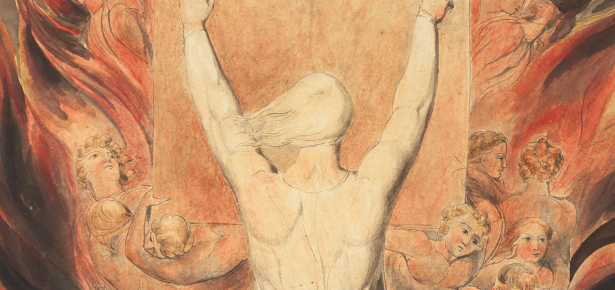

Romantic literature grows out of these diverse religious influences. Bigoted caricatures, including ‘orientalist’ stereotypes, pervade dramas and novels, but some authors drew positively on spiritual insights gained through experiences abroad. Lord Byron, known for his libertinism, traveled widely in the Middle East and wrote poetry that reflects astonishing linguistic encounters. In fact, music, painting, politics, and natural philosophy all exhibit marks of an emerging religious pluralism that make simplistic notions of Romantic secularity difficult to sustain.

In returning to the past, we discover new networks of religious and literary exchange for closer examination in the future. None of this means that British Romantics were any less radical in the ways they reinterpreted or appropriated religion in their poetry and prose. But their writings manifest a far less homogenous religious (or areligious) context than we might otherwise suspect. In this, the effort to expand the British literary canon depends on a new effort to recover the religious diversity of the past.

Latest Comments

Have your say!