If you look at the title page of my new book, Shakespeare’s ‘Lady Editors’: A New History of the Shakespearean Text, you might notice that there’s something missing – the space beneath my name is blank, an empty void where, usually, you would see an author’s institutional affiliation. In the three years since I submitted my dissertation, I have not secured a full-time academic job, let alone a permanent one. This puts me in very good company. There have been countless articles and think-pieces written on the crisis in the academic job market, the slashing of tenure-track or permanent jobs, and the rise in casualization in the higher education sector, so I’ll refer you to those for the broader picture. I don’t want to position myself as having special insights into the job market, and I certainly can’t address even a quarter of its issues, or their subtleties, here; however, I’d like to narrow in on one of its consequences – the growing pressure to publish monographs even when working without full-time affiliation.

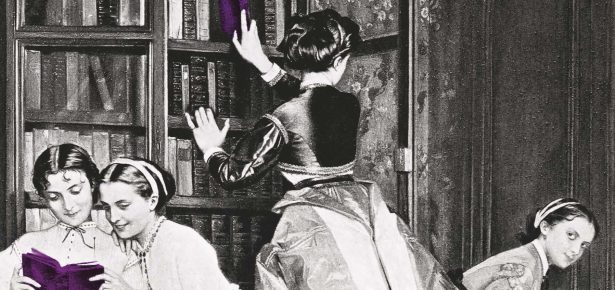

It’s particularly appropriate to talk about this in connection with my book because discussing the conditions of academic work is part of what this book does. In Shakespeare’s ‘Lady Editors’, I explore the lives and labours of almost seventy women who edited Shakespeare prior to 1950. One of the interesting demographic trends I noticed while researching is that many of them never held university jobs, even after women’s colleges and coeducational universities made those jobs available to women. Although this seems strange to imagine now, when most editing is done by an extremely limited number of academics, the majority of the editions discussed in the book were published around the end of the nineteenth century into the early twentieth, meaning that these women editors were active during the dawn of modern Western literary studies. And as literature became a subject to be studied in schools and universities, and thus, an official academic discipline, there came into existence a new subspecies of humanity – the Professor of English Literature.

In all seriousness, the professionalization of English studies, signalled by the creation of English departments and the codification of critical methods, dramatically changed the terms of engagement for people who studied, taught, or wrote about literature, sorting those people into two new categories, ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’. Whereas before, no one who edited Shakespeare held a degree in English literature because no such thing existed, people now emerged from universities with official accreditations telling the world that they were trained in literary studies, and thus particularly qualified to do this sort of specialized work. And as professionalization became more entrenched, fewer people without university posts were hired to produce ‘big’ editions of Shakespeare. Listing a famous university, or any university, under the editor’s name on the title page conferred prestige and authority upon the edition. Although this affected both men and women editors, it affected what we might call the proto-alt-ac women chronicled in my book disproportionately.

With this longer history in mind, I promised myself when I signed my contract with CUP that I would publicly discuss the conditions under which I was able to publish this book, because I am concerned about the precedent that I, and other independent/contingent/precarious scholars, are setting by securing contracts on monographs. [To be clear, I’m expressing my own opinions here, not speaking for CUP.] On the one hand, of course deserving scholarship should be published, full stop; however, I don’t want to create the impression that completing and publishing a monograph without affiliation or institutional support is achievable for everyone, no matter how good their potential books are. Although it’s uncomfortable to talk about, I want to acknowledge and own that my ability to do this was enabled by countless forms of privilege. Just to name a few: I’m an upper-middle-class white woman in good physical health who comes from a family with other academics; I attended name-brand institutions that look good on my CV and through which I made useful connections; perhaps most importantly, I am debt-free and had savings and family support in the years after I finished the PhD, meaning that, unlike many of my fellow ECRs, I didn’t have to hustle simply to pay for rent and food.

Many of these characteristics are echoed in the lives of women editors discussed in the book, such as the reliance on family support. Numerous academic women, including those with university jobs, lived with, and relied upon, widowed mothers and single sisters. Katharine Lee Bates, for example, lived with her mother, Cornelia, and her sister Jeannie throughout their lives. Cornelia and Jeannie managed domestic issues in addition to supporting Bates’s academic work – Jeannie often served as Bates’s amanuensis – meaning that Cornelia and Jeannie occupied the same support role in Bates’s life that many wives, mothers, and sisters have filled for male academics and intellectuals. Thoreau’s mother doing his laundry at Walden Pond, anyone?

These days, even for those like me with the privilege of time and support, access and cost remain insurmountable barriers to publication for many unaffiliated or contingent scholars. As an alum of a wealthy school, a person with a wide academic network, and a resident of a college town with a large research library, I had exponentially better access than most to physical and digital resources – financially prohibitive on the individual subscription level – which enabled me to revise my dissertation and carry out new research. Once I’d finished the process, the privilege of having money saved allowed me to cover my image permissions fees, which remain exorbitant, even when dealing with some of the biggest institutions in the world.

Oh, and I wrote (hopefully) a good book. But in a way, that’s the least of it. One theme in what is sometimes disparagingly called ‘quit lit’ is a sense of mourning for the enormous amount of brilliant scholarship being lost as people leave – are forced out of – full-time academic life. I feel this acutely now that I’m one of the exceptions that proves the rule. My particular set of circumstances would be so difficult to replicate. Impossible, really, if you take into account the fact that a global pandemic temporarily ended my part-time job, leaving me with, shall we say, unexpected time to write and revise. There are plenty of books as good as (or better than) mine that will never be published, never even be written. Their authors are shuttling between multiple universities to teach courses on short-term contracts, not even making a living wage. They might be supplementing that with non-academic work, or moving into alt-ac work full-time. They are being sucked into a gig economy that cloaks itself in the ‘prestige’ and white-collar nature of academia.

This cycle is insidious in part because, the more competitive the market becomes, the more individual candidates can be rewarded for having that first monograph contract in hand, while those who simply do not have the time or access to complete their books suffer unfairly in comparison. It’s a catch-22. On the one hand, no one wants to discourage independent/contingent scholars from publishing, if they can, or make it harder for them to do so. On the other hand, it would be destructive to further normalize a system in which a published book or book contract is a minimum requirement for a tenure-track or permanent job. To a hiring committee, these CV lines are seen as proof that the candidate can produce at scale, making them more likely to meet tenure requirements or contribute to departmental REF scores; however, in reality, a published monograph probably speaks to the candidate’s privilege and luck as much as, if not more than, their possible future productivity. Any candidate’s output, if hired, could potentially be disrupted by life’s vagaries; however, it’s worth mentioning that women’s academic careers remain significantly more likely to be negatively affected by outside factors like parenthood, caretaker responsibilities, or global pandemics. During the Covid lockdown, I benefitted from the privileges not only of having support around me, but of being single and having no one to care for but myself. As I discuss in the book, some women editors both published and took care of children, parents, siblings, or husbands. Those who chose to marry often struggled with the challenges that marriage and motherhood caused in their intellectual lives. Having already been forced out of academic jobs, pressured by unofficial-but-implied ‘marriage bars’ to resign from their posts after marriage, they had to fight for every second that they spent researching or writing. And undoubtedly, for every one woman who succeeded, there were many more who had to give up their scholarly work completely.

Of course, it’s impossible to address the challenges of publishing monographs without discussing the academic publishing industry. I’m very grateful to CUP, and my editor, Emily Hockley, in particular, who have put immense faith in me, an unaffiliated, early-career scholar. I’m also grateful to them for giving me a platform to discuss this issue. Publishers and academic institutions are just two factors in the complex economic and social dynamics at play here, but they are two of the bigger factors, something that I know editors and publishers are acutely aware of. The academic publishing industry has also faced significant challenges in the past decades, and again, I’ll refer you to those better versed in these issues to speak to their nuances. Here, I’ll simply say that if we – and by ‘we’, I mean the entire, complex ecosystem that creates and consumes scholarly work – want to ‘save’ scholarship from being lost when its authors leave academia, we must rethink how published academic work is remunerated in a world in which decreasing numbers of academic monographs are purchased. Just as it did when it entered the universities in the late nineteenth century, the study of literature as a profession has undergone a seismic shift. It’s no longer enough to say that writing books is part of the salaried job of every academic – it unequivocally is not, even for some in permanent or tenure-track posts.

All of this must be done, however, without losing sight of the bigger picture, and the bigger problem – precarity. Academia is cripplingly reliant on underpaid and unpaid labour, whether that comes in the form of exploitative short-term teaching contracts, university or department-level service work, field service such as peer reviews or terms on editorial boards, or simply the emotional labour required to support students, to fight systemic inequalities and injustices, and to survive in a dysfunctional industry. Those who are given the least are increasingly unable – or, perhaps more importantly, unwilling – to give of themselves while receiving nothing in return. Recent strikes and industrial actions across the labour market, in industries ranging from manufacturing, to hospitality, to, yes, higher education, suggest that academia has reached an inflection point. Business as usual is over. What comes next?

On an individual level, I don’t have an answer to that question, and in that uncertainty, I think about my women editors, and the professional/amateur binary. Am I still a ‘professional’ scholar without an academic job? Or have I moved into realm of the amateur, with all its negative connotations, becoming, as an obnoxious man once called Shakespeare editor Charlotte Stopes, an ‘enthusiast’? Either way, I’m lucky – my book exists, my research is preserved. For untold numbers of my peers, that is not be the case. What comes next for them? After all, on a purely practical level, why should they publish? Increased success on the job market is a false promise simply because the numbers are against you, no matter how long your CV – academic hiring is often extremely arbitrary. Why should ECRs feel incentivized to do the work of research, writing, and publishing solely in the hopes that it will, as a recent tweet put it, make them more likely to draw the academic equivalent of a winning Power Ball ticket? This is more than a pragmatic, individual question; it’s an existential one.

Latest Comments

Have your say!