How and why did the Haitian Revolution happen? How did enslaved people from varying backgrounds come together to orchestrate the most radical political event of the modern era – the only revolt of enslaved people to abolish slavery, overturn colonialism, and create the first free and independent Black nation in the Americas?

These and other questions lie at the heart of my interest in studying and writing about the Haitian Revolution, questions that have driven (and perhaps, at times, even plagued) me and resulted in my book, Rituals, Runaways, and the Haitian Revolution: Collective Action in the African Diaspora. In approaching this project, my initial aspirations were to understand how and why Black people mobilize for transformative societal change, with specific curiosity about how religion can influence collective action. With only a vague understanding of Karl Marx’s often-quoted sentiment that “religion is the opiate of the masses,” I had a similarly vague notion that the sentiment was untrue for people of African descent in the Americas. As I encountered the work of Cedric J. Robinson and several other works in African diaspora studies, I found historical and theoretical legitimation for the idea that Black people’s forms of resistance, social movements, revolts, and revolutions against exploitation and oppression have their origins within spheres of sacred consciousness and practices. I was interested in exploring this perspective as a way of affirming Black religion and its transformative potentiality rather than dismissing it as a weapon of the elite against subordinate groups.

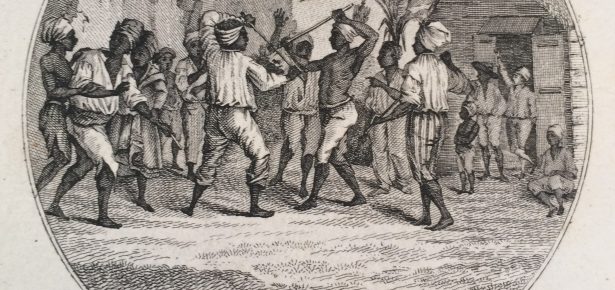

My interests were further confirmed as I learned more about the Haitian Revolution and its beginning phases, particularly the Bwa Kayman (Bois Caïman) ceremony that occurred merely one week before the mass insurrection of 1791. The ceremony was a secret gathering of enslaved people from across colonial Haiti’s northern plantations who plotted the demise of the plantation system, using oaths of secrecy to build solidarity, as well as ritual sacrifice and the supplication of African spirits to provide the soon-to-be rebels sacred authority and protection during the revolt. The fact that a woman, known as Cécile Fatiman, was named as one of the main presiders of the ceremony deepened my interest in the Haitian Revolution and the organizational forms, sacred practices, and patterns of resistance that undergirded the massive insurgency.

I began to wade through literatures on the Haitian Revolution, Haitian Vodou, and Black resistance in the Americas in search of answers for how enslaved people in one of the deadliest slave colonies were able to successfully transform the material conditions into which they were forced via the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. I found contention among scholars who disagreed on the origins and significance of the Haitian Revolution and the events that led up to it. Some works emphasized the role of free people of color and the philosophical ideas of the French Revolution as the primary spark that ignited the Haitian Revolution. Others suggested that enslaved people’s escape from bondage – marronnage – and the religious system of Vodou were central organizing tools that supported the insurgency. Yet others dismissed these earlier mechanisms of resistance and contended that no revolutionary consciousness could have existed among the enslaved people of colonial Haiti prior to 1789. I puzzled the idea that enslaved African people did not, or rather more pointedly, could not think about or conceptualize revolution separate from ideologies propagated in Europe. I set out to identify how people of African descent developed a collective consciousness, and the processes that politicized that consciousness and resistance activities towards liberation from slavery and independence from colonialism.

As a Black Studies scholar and sociologist, I was concerned with how to use conceptual and theoretical tools to begin to answer questions that historical scholarship had not yet resolved. Insights in African diaspora studies, Atlantic world history, the sociology of social movements, and other disciplinary arenas like anthropology and religious studies helped me explain archival findings in ways that shed new light on the collective agency of colonial Haiti’s enslaved population. I approached the work with an understanding that social structures shape material conditions and people’s lived experiences; that human interactions and meaning-making activities then shape the character of their social actions; and then those social actions impact and produce social change. This was particularly helpful as I used quantitative and qualitative methods to engage an under-utilized dataset of thousands of advertisements for enslaved runaways – maroons – and other primary and secondary sources to tell the story of how enslaved people, maroons, and a few free people of color developed social networks that facilitated a sense of shared consciousness and racial solidarity that was key to the Haitian Revolution’s success. This story is not one that is solely concerned with the volume of advertisements under study, it is about how we can make sense of such sources in a way that re-humanizes people of African descent, who had been dehumanized in untold ways by the violence of enslavement and the silences of history.

Latest Comments

Have your say!