In a rural area, now part of modern Shanghai, a 34th-generation descendant is alleged to have buried the robe and cap of Confucius (Kongzi; 551-479 BCE), over a thousand years after his death. Another thousand years later, highly educated local elites and government officials built a unique shrine for worshiping Confucius in this unlikely place, which was known as Kongzhai (“Kong Residence”). My book The Aura of Confucius: Relics and Representations of the Sage at the Kongzhai Shrine in Shanghai reconstructs its history, which was later suppressed, but Kongzhai’s significance goes beyond a case study of censorship. Its evolution illustrates the power of Confucian religious expression and the veneration of Confucius himself through physical artifacts and visual images.

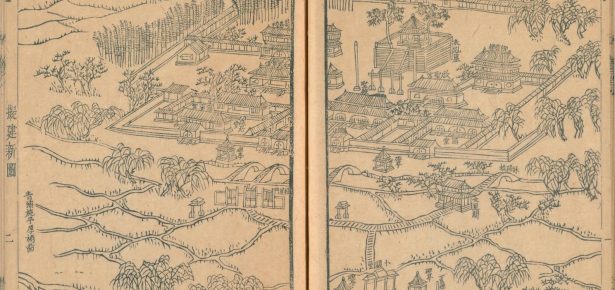

Kongzhai’s “relics” were never actually seen. Instead, their presence was made visible by the Tomb of the Robe and Cap, built in the early 17th century. A century later, Kongzhai also boasted three separate temple-halls for sacrifices respectively to Confucius, his father, and five generations of ancestors. An associated academy within the precincts included a tower for imperial calligraphy, a library, lecture court, and several pavilions. A building displaying portraits of Confucius and narrative pictures illustrating his life enabled visitors to “see” the ancient sage and imagine themselves among his disciples, while experiencing the auspicious ambience created by his unseen garments and enjoying the fellowship of literati colleagues. In 1705, the Kangxi emperor bestowed his own calligraphy certifying Kongzhai as the “Surviving Emblem of the Sage’s Traces,” and high officials contributed to a comprehensive gazetteer documenting its long history. But subsequent emperors disavowed its improbable legends, starting a decline that was only partially reversed in the 19th century. Kongzhai suffered further in campaigns against feudalism and superstition after the 1949 revolution, and local Red Guards destroyed it during the Cultural Revolution.

Unlike the many Confucian temples in mainland China that have been restored or rebuilt in recent years, Kongzhai has completely disappeared from the landscape. Its history has been deliberately obscured and its gazetteer miscatalogued as a book about Confucius’s home in Qufu, where his descendants maintained an ancestral temple, cemetery, and mansion. It has not been revived because its defining features conflict with conventional views of Confucianism as a purely secular moral philosophy. Instead, Kongzhai’s origins and development highlight the functions of relics, sculptural icons, pictorial images, and miracle tales in Confucian contexts and demonstrate the influence of Buddhist and Daoist forms.

My reconstruction of Kongzhai’s history and its representations of Confucius has often required speculation based on evidence that is sometimes ambiguous, particularly for its situation during the 20th century. At present (October 2021), it appears that Kongzhai’s former existence is finally being acknowledged, at least by local authorities of the district where the shrine formerly stood, and area residents have participated in a recently published study. While the resurrection of Kongzhai still seems unlikely, the possibility may now be conceivable.

Latest Comments

Have your say!