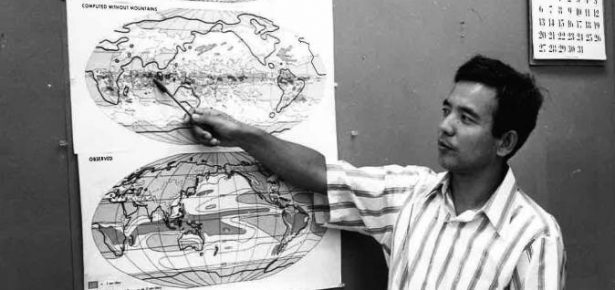

Syukuro Manabe explains how mountains affect the Earth’s climate

(1972 photo, courtesy of NOAA/GFDL)

Climate scientist Syukuro Manabe shared the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the physical modelling of Earth’s climate, which led to the first reliable predictions of global warming. Manabe’s journey to becoming a climate science pioneer began in the 1950s, in post-war Japan, when jobs were scarce. Scientists in the United States had recently built the world’s first computer model to predict weather and were extending it to predict climate. Manabe was hired from Japan to add a component to this model to calculate how sunlight and heat are reflected and absorbed by the atmosphere. Starting with a simple climate model of the atmosphere based on the laws of physics, and then building more complex models that included the ocean, Manabe’s work in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrated that increasing carbon dioxide will lead to global warming.

The Nobel award has finally (and some might say, belatedly) recognized that climate modelling is an important application of the basic principles of physics. Interestingly, a handful of contrarian physicists have been among the most vociferous critics of using climate models for prediction. Their main criticism of climate models has been that they imperfectly represent very small-scale processes like clouds, leading to imprecision in climate predictions. But climate scientists use such imperfect representations out of necessity, not out of choice (and the contrarian physicists have failed to offer more precise alternatives for predicting climate).

The simple prediction models developed by Manabe and other pioneering scientists such as Jim Hansen form the foundation for the much more elaborate climate models that are in use today. The early models used thousands of lines of computer code; today’s state-of-the-art models use millions of lines of code. But this massive increase in code complexity has only resulted in a modest improvement in the precision of global predictions, although climate models have become more realistic in other aspects. The global predictions made many decades ago by the simple models of Manabe and others remain approximately true even today, because they capture the essential principles governing Earth’s climate. The Nobel award recognizes this.

By breaking down the atmosphere and ocean into millions of representational grid boxes, and predicting the time evolution of each box, the computer models of climate have become concrete manifestations of the abstract philosophical concept of Laplace’s Demon – a vast intellect that could predict the trajectory of every atom in the universe and therefore had perfect knowledge of the past and the future. My book, The Climate Demon, traces the fascinating history of climate prediction, from the simple climate models of Manabe and Hansen to the elaborate Earth System models of today. Along the way, the book explores the philosophical conflict between simplicity and complexity in science, contrasting the approach of a highly precise discipline like physics with the necessarily imprecise discipline of climate science. Finally, the book extrapolates the future of climate prediction, by analyzing the promises and pitfalls of using machine learning for prediction, and the potential benefits of new, massively-parallel “Exascale” supercomputers. The book concludes by emphasizing the value of predictive models in dealing with the severe risks posed by anthropogenic climate change.

Latest Comments

Have your say!