There are not many good things about this COVID-19 era we are living in. One of the few positive side effects one might celebrate, though, is that it has permitted many of us to rediscover the joys of slowing down and paying attention to things that we have been otherwise thoughtlessly passing by, looking at the familiar with a renewed sense of curiosity and wonder. Writing in Baghdad, over seven centuries ago, Zakariyya al-Qazwini (1203-1283 CE) made a similar observation, not about a virus but about the world. In an encyclopedic work he wrote entitled The Marvels of Creation, he exclaims that everything in the world is cause for our wonder; familiarity and frequent observation are the only reasons our fascination is dulled.

Marveling at the world was a pious act for medieval Muslim authors: Contemplating God’s creations was a way to get closer to knowing God. However, wonder was also the defining aspect of classical Arabic literary aesthetics. Good poetry, according to this outlook, tries to recreate the experience one has when faced with what is out of the ordinary, novel, or mysterious. Whether dealing with the divine or with mundane earthly matters, the effect of the poetic was seen as the evocation of a sense of wonder in the listener.

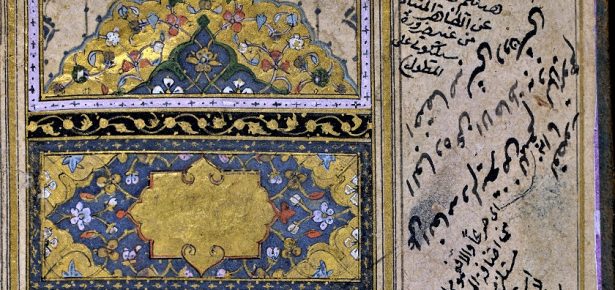

My recent book, Arabic Poetics: Aesthetic Experience in Classical Arabic Literature, uncovers for the first time this aesthetic of wonder through analyzing a range of Arabic texts that have come down to us from roughly the tenth to the fourteenth century, which can be described as “literary theory.” One of the main thinkers to develop this aesthetic theory of wonder was ‘Abd al-Qahir al-Jurjani (d. 1078 or 1081) in a work entitled The Secrets of Eloquence (which has yet to be translated to English, although a German translation does exist). In it, Jurjani attributes poeticity in literary expression to its ability to make the listener or reader slow down, demanding one’s scrutiny, contemplation, and analysis. Unlike ancient Greek poetics, which was primarily concerned with drama and narrative plot, Arabic poetics looked at what makes linguistic expression beautiful and affective. Jurjani and his successors, hence, developed theories of what makes poetic linguistic expression, such as metaphor, simile, and the numerous rhetorical figures that exist in Arabic, able to distance meaning, conceal it, or mislead the listener in such a way as to make him slow down, contemplate, and eventually discover the intended meaning – a theory I describe as wonder.

This aesthetic of wonder, however, was not always the dominant aesthetic championed by critics. It only started to develop at the turn of the eleventh century CE after almost two centuries of critical writing in Arabic. Earlier criticism was concerned with different aesthetic criteria, namely the truthfulness and accuracy of poetry, as well as its natural simplicity. These criteria were largely in response to the new Abbasid style of poetry that developed in the late eighth and ninth centuries, which tended to be more ornate, fantastical, and affected, compared to the – by then – “classical” ideals of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry. The theory of wonder, the book argues, represents a major paradigm shift from this earlier framework of thinking: Instead of prioritizing one style over another, the new wonder-based school of criticism developed logical explanations for the effect of beautiful speech in general whether it be the kinds of elaborate fantastic metaphors found in the new style of Abbasid poetry or a simple perfectly constructed simile one might find in pre-Islamic poetry.

Significantly, the aesthetic of wonder also formed the basis of post-tenth-century demonstrations of the miraculousness of the Quran, where the indirect effect of syntax on meaning is credited with the inimitable awe-inspiring nature of the Quran. Arabic interpretations of Aristotle’s Poetics also exhibit an underlying aesthetic of wonder, where poetic reasoning constituted a make-believe kind of logic (philosophers of the Islamicate world classified the Poetics as part of the Organon, Aristotle’s books on logic), which results in discovery and wonder. The theory of wonder thus constituted a comprehensive explanation of linguistic beauty that could be universally applied to old and new poetry, the Quran, and even in logic.

I don’t always find it easy to justify my work as an academic during trying times like these. However, it is at once reassuring and humbling to heed the values of an old aesthetic: slow down, contemplate, and rediscover our familiar surroundings with curiosity and wonder.

Latest Comments

Have your say!