What happens in the afterlife has been one of the ‘burning’ questions that preoccupy humanity. As such, its representations provide a perfect platform to dip into the past by looking at art through the eyes of its contemporary people. So, please join me for a brief visit in the fourteenth century.

The year is 1373. The inhabitants of the village of Kitiros, in the south-western part of the island of Crete, have just completed the decoration of their parish church. At the time, Crete was under Venetian rule, but in their vast majority the rural areas were inhabited by Greek speaking, Christian Orthodox population. As such, the church is dedicated to Saint Paraskevi, a female Orthodox saint. Its iconographic programme includes the punishments of damned in Hell, the brutal and eternal suffering of those who disobey the law of both God and man.

Unlike present-day, in the fourteenth-century the availability of images was rather limited. One of the main places one could have encountered rich and colourful imagery was in a church. Their visual impact, combined with the preaching of the priest, would have been profound.

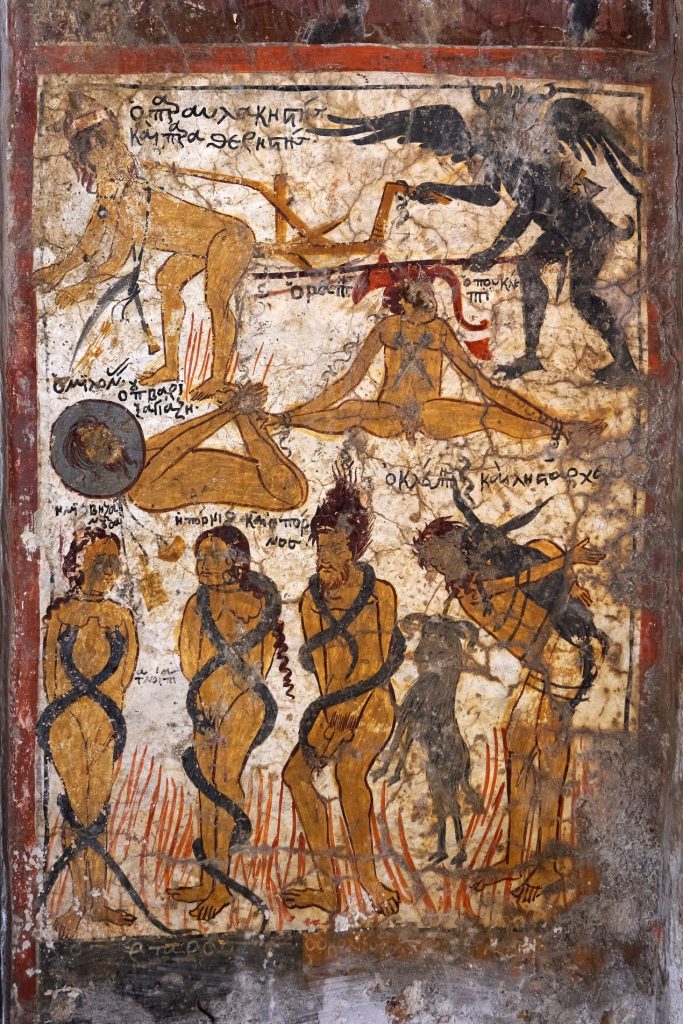

Among the sinners punished in Hell at Kitiros, are ‘Those Who Sleep on a Sunday’ rather than attending the liturgy (Fig. 1; painting rather damaged). The faithful standing before this wall painting on a Sunday morning would have known that this was not a sin they were committing – if Hell were waiting for them on the other side it certainly would not have been for not attending Sunday Mass. Other sinners include a ‘Man Who Ploughs Over the Boundary Line [of his field]’, a ‘Miller Who Cheats while Weighing [flour]’, a ‘Tailor Who Cheats [his clients] and a ‘Goat Thief’ – all thefts punishable by penal law and explicitly forbidden in the Ten Commandments. Furthermore, in the fourteenth-century such actions could have made the difference between life and death – less land to produce agricultural products, less flour, less meat, all equalled less chances of survival for a farming family. Among the sinners are also a ‘Woman Who does not Breastfeed her Children’, another matter of life and death in an era where no substitute formula was available, and a man and a woman ‘Who Fornicate’ (have carnal relations outside marriage) (Fig.2).

These images were not only projecting a powerful incentive for the Christian villagers to stay on the right path, they were also reassuring them that those who did not were going to suffer insufferable pain for ever. The hope for a blissful eternal afterlife following the hardships of their fourteenth-century rural lives, could not be underestimated.

The examination of the representations of Hell in the eastern Mediterranean reaches beyond the study of Christian religion; it includes experiencing a social, legal and economic past in search of building a learned future. Because, studying the past is not only about continuity and what we can relate to, but also what was different and what it can teach us. Therefore, looking at these pictures makes us question what the moral taboos of our own time are, and how they are being reinforced.

Latest Comments

Have your say!