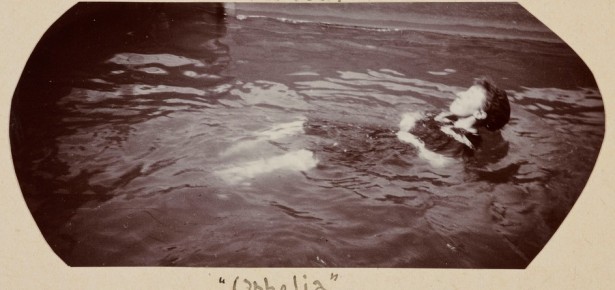

One afternoon at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight in the summer of 1896, Louise Margaret, Duchess of Connaught, took this photograph of her niece, Helena Victoria, swimming on her back. The photograph was pasted into an album of family photos—holiday snaps from the 1890s, a decade in which photography became much easier to practice as an untrained amateur, thanks to the commercial availability of pre-treated photographic plates. Either Louise Margaret or her husband, Arthur (who was the third son of Queen Victoria), mounted it in an album and wrote on the mount, “Ophelia.” The album was kept, passed on in the family; then, when the royal family’s collection of photographs were brought under the auspices of the Royal Collection in the 1970s, it became part of a national collection: a historical object; an artefact pointing towards a performance.

What did Louise Margaret mean to suggest by this caption? And, perhaps more importantly, what did she suggest without meaning to? I imagine she thought it was charming: the same way we might write ‘Toad of Toad Hall’ on a picture of a child pretending to drive a car. Posing as literary figures and recreating the compositions of famous paintings were regular leisure activities for the royal family at the time: maybe this scene looked to them like an accidental tableau-vivant. Members of the family had posed as Romeo and Juliet, dying in a mausoleum mocked up in the hall at Balmoral, and as the Princes in the Tower, innocently waiting for the men sent to murder them. The Victorians were not put off by morbid photographs. The Victorians invented morbid photographs.

There was probably nothing unsettling about this photograph at the time of the exposure. Other pictures taken the same day, titled more prosaically ‘Bathing at Osborne, August 1896,’ show this most formal of families looking unusually relaxed. Helena Victoria seems to have been teaching her younger cousins to swim. The Royal Collections’ online catalogue suggests that the ‘playful title’ is a further indication that this photograph represents a happy memory.

But this photograph is haunting to me—there is something callous about the handwritten caption, “Ophelia.” At its absolute mildest, it requires us to imagine that the woman in the photograph is dead.

The woman in the photograph is dead. She didn’t drown; she died almost fifty years later, five months after attending the wedding of her distant cousin, now Queen Elizabeth II. Like the ‘Winter Garden photograph’ of his mother as a child that haunts Roland Barthes in his extraordinary meditation on grief and photography, Camera Lucida, the photograph invites us to look queasily backwards, to feel ‘the vertigo of time defeated’. Barthes writes: ‘In front of the photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die: I shudder, like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred’ (Barthes, 96-7). Helena Victoria’s youth may have been effervescent in 1896, but the photograph stills her reclining body and petrifies her in time.

And the caption asks us to imagine that she is ‘playing dead’ in the picture; effectively, to understand it as part of a performance. But the photograph doesn’t convince as a tableau-vivant performance, partly because this isn’t really a scene from Hamlet. Ophelia dies offstage: the queen enters with the news of her accidental drowning, delivered as a conspicuous rhetorical set-piece. However vivid the description of Ophelia’s ‘weeping brook,’ ‘fantastic garlands’ and ‘muddy death,’ the play teaches us to be suspicious of reports about offstage characters. The death scene, offstage, occupies an indeterminate space between euphemism and a painful truth.

The informal composition suggests that this is not actually a record of a performance, even a momentary one. Instead, Ophelia’s madness and despair have been overlaid onto Helena Victoria’s floating body retrospectively by the label. We are invited to read the photograph through the spectacular deaths of Victorian art, most famously that of John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851). Look long enough, and the pale shape of her arms folded across her body start to look like they have been arranged in the morgue; her pale legs appear to be sinking into the depths of the water. The invitation to read Helena Victoria’s body as a spectacular corpse makes the act of captioning into a kind of violence – as Susan Sontag suggests, photography ‘turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed […] to photograph someone is a sublimated murder’ (On Photography, 14).

In Still Shakespeare and the Photography of Performance, I wrote about the impact of photography on the afterlife of Shakespeare’s works, thinking particularly about the way that photographs cause these strange collisions – in this case, between a fictional woman drowning, and a real woman teaching her cousins to swim. Because it’s so easy to take them out of context, to caption and re-caption them, and to display them in different settings, photographs can create alienated, nebulous, and belated varieties of Shakespearean ‘performance.’

Still Shakespeare and the Photography of Performance is now available from Cambridge University Press. You can read about my current work on Shakespeare and the Royal Collections at https://sharc.kcl.ac.uk

Image courtesy of Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019

www.rct.uk/collection/2802284

Latest Comments

Have your say!