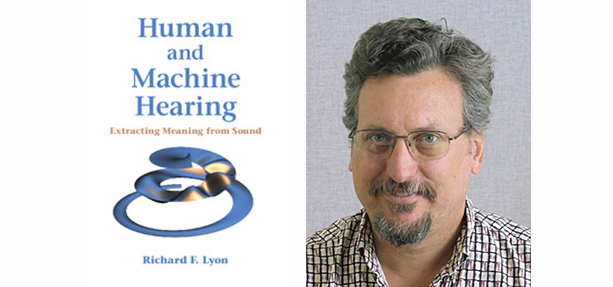

Based on positive experiences of marrying auditory front ends to machine-learning back ends, and watching others do the same, I am optimistic that we will see an explosion of sound-understanding applications in coming years. At the same time, however, I see too many half-baked attempts that ignore important properties of sound and hearing, and that expect the machine learning to make up for poor front ends. This is one of reasons that I wrote Human and Machine Hearing.

Machines that listen to us, hear us, and act on what they hear are becoming common in our homes, with Amazon Echo, Google Home, and a flurry of new introductions in 2017. So far, however, they are only interested in what we say, not how we say it, where we say it, or what other sounds they hear. I predict a trend, very soon, toward much more human-like hearing functions, integrating the “how”, “what”, and “where” aspects of sound perception to augment the current technology of speech recognition. As the meaning of sound comes to be better extracted, even the “why” is something we can expect machines to deal with.

Some of these abilities are becoming available already, for example in security cameras, which can alert you to people talking, dogs barking, and other sound categories. I have developed technologies to help this field of machine hearing develop, on and off over the last 40 years, based firmly in the approach of understanding and modeling how human hearing works. Recently, progress has been greatly accelerated by leveraging modern machine learning methods, such as those developed for image recognition, to map from auditory representations to answers to the “what” and “where” questions.

It is not just computer scientists who can benefit from this engineering approach to hearing. Within the hearing-specialized medical, physiology, anatomy, and psychology communities, there is a great wealth of knowledge and understanding about most aspects of hearing, but too often a lack of the sort of engineering understanding that would allow one to build machine models that listen and extract meaning as effectively as we do. I believe the only way to sort out the important knowledge is to build machine models that incorporate it. We should routinely run the same tests on models that we run on humans and animals, to test and refine our understanding and our models. And we should extend those tests to increasingly realistic and difficult scenarios, such as sorting out the voices in a meeting — or in the proverbial cocktail party.

To bring hearing scientists and computer scientists together, I target the engineering explanations in my book to both. A shared understanding of linear and nonlinear systems, continuous- and discrete-time systems, acoustic and auditory approaches, etc., will help them move forward together, rather than in orthogonal directions as has been too common in the past.

Find out more about the book and check out Richard Lyon’s commentary on, and errata for, Human and Machine Hearing

Latest Comments

Have your say!