Turing’s imitation game, also commonly known as the Turing test, is undoubtedly a key component in any study of artificial intelligence or computer science. But it is much more than this as it also provides insight into how humans communicate, our unconscious biases and prejudices, and even our gullibility. The imitation game helps us to understand why we make assumptions, which often turn out to be incorrect, about someone (or something) with whom we are communicating and perhaps it helps to shed light on why we sometimes make seemingly irrational conclusions about them.

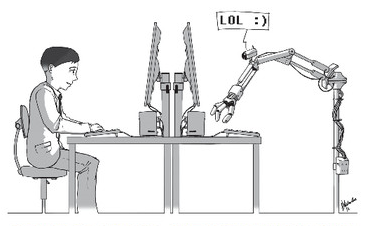

In the chapters ahead we’ll look at the game in much more detail; however in essence it involves a direct conversational comparison between a human and a machine. Basically, the goal of the machine is to make you believe that it is in fact the human taking part, whereas the human involved is merely being themselves. Both the human and the machine are hidden, so cannot be seen or heard. The conversation is purely textual with slang, idiom, spelling mistakes, poor grammar and factual errors all being part of the mix.

If you put yourself in the role of an interrogator in the parallel test then it is your job to converse with both a hidden human and a hidden machine at the same time and, after a five-minute period as stipulated by Alan Turing himself, to decide which hidden entity is which. If you make the right identification then that’s a point against the machine whereas if you make a mistake or you simply don’t know which is which then that’s a point for the machine. If a machine is successful in fooling enough average interrogators (one interpretation of Turing’s 1950 work is 30%), then it can be said to have passed the Turing test.

Actually restricting the topic to a specific subject area makes it somewhat easier for the machine, because it can direct the interrogation to its knowledgebase. However, Turing advocated that the machine be investigated for its intellectual capacity. Thus we should not restrict the topic of conversation at all, which we believe is an appropriate challenge for machines of today, and which is much more interesting for the interrogator and is in the spirit of the game as (we feel) Turing intended. That said, in the experiments we have conducted we were the first to include children to take part both as interrogators and hidden humans. We have therefore asked all human and machine participants to

respect this situation in terms of the language used.

It is clear to see that when the game was originally set up by Alan Turing in 1950 such skills as a machine fooling people into believing that it is a human through a short communication exercise would have been very difficult for most people to understand. However, in introducing the game, Turing linked it inextricably with the concept of thinking and there is a nice philosophical argument in consequence concerning how one can tell if another human (or machine) is thinking. This was a brilliant link by Turing which, as a result, has brought about a multitude of arguments between philosophers and researchers in artificial intelligence as to the test’s meaning and significance.

But Turing’s game has extended way beyond the ivory towers of academia and now has a truly popular following. As an example, the Wikipedia entry for the Turing test typically receives 2000 to 3000 views every day. On one day, 9 June 2014, after it was announced that the Turing test had been passed following our 2014 experiment (about which you will be able to read in Chapter 10), the same page received a total of 71,578 views, which is quite an amazing figure. As a direct comparison, popular Wikipedia pages, such as

those for Leonardo DiCaprio or The Beatles, received respectively only 11,197 and 10,328 views on that same day.

But with this popular following comes misconceptions as to what the game is about. In particular, a sort of folklore belief has arisen that the Turing game is a test for human-like intelligence in a machine. This belief has been fuelled by some academics and technical writers who perhaps have not read the works of Turing as thoroughly as they might. Hopefully this book will therefore be of some help to them!

Let us be clear, the Turing test is not, never was and never will be a test for human-level or even human-like intelligence. Turing never said anything of the sort either in his papers or in his presentations. The Turing test is not, never was and never will be, a test for human-level thinking. Turing didn’t say that either.

However this does beg the question of what exactly does it mean to pass the Turing test. As will be discussed later, Turing introduced his imitation game as a replacement for the question “Can machines think?” Turing (1950). The conclusion by many as a result of this is that if a machine passes the test then we have to regard it as a thinking machine. However Turing saw a clear distinction between the ways machines and humans think. He continued, “May not machines carry out something which ought to be described as thinking but which is very different from what a man does?”. Human-like thinking for machines was therefore not on the radar as far as Turing was concerned.

In the same article Turing also wrote, in reference to the year 2000, “One will be able to speak of machines thinking without expecting to be contradicted”. Noam Chomsky (2008) wondered that of all the ways a machine could display intelligence why did Turing choose a test involving human language which is merely one part of human intelligence.

In the imitation game a machine is interrogated by a human and is directly compared, with regard to its ability to communicate, with another human who is being interrogated in parallel. If a machine passes the Turing test it exhibits a capability in communication. In that sense it surely involves one aspect of human intelligence as pointed out by Chomsky. This does not mean that the machine displays human-type intelligence or consciousness.

Perhaps by trying the game yourself you’ll be able to get a better idea of what it’s about, how it is not as easy as one might at first imagine, and also how much fun can be had from it. To start with, have a look at this conversation, where you are challenged to determine whether input and output are human or machine. This is taken from an actual discourse, as transcribed, errors and all.

Input: i like kittens

Output: my cat is pink

Input: are you smartß

Output: That is mean ‘BRAIN?

Input: could you go nude for me?

Output: we are in a dark room and naked

Input: that sucks

Output: seems to me you are in a crappy room with trash and mail

Input: you are not nice

Output: i have a good friend

In fact the input and output were both machines; were you correct? The input was from the machine Elbot (Artificial Solutions). In a 2009 email, its developer, Fred Roberts, stated that “Currently I have a feature in Elbot to collect user inputs according to certain rules, then automatically code a generalized keyword condition to associate with the user input, and finally reuse the user input as the bot response. That is what you see in output – actual user inputs reused as bot answers. At the moment the knowledge is too small to be meaningful, but in a few weeks it could be awesome”.

Don’t worry if you guessed the identity of the conversationalists incorrectly. In this book you will have further opportunity to test your own skills in distinguishing human from machine. We hope you enjoy the actual imitation game conversations we present and appreciate the marvel of human communication as Alan Turing did, and understand why in reality it is so difficult to create talking robots as we see them in science fiction movies, from Maria in Metropolis (1927), through HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), to Ava in

Ex Machina (2014).

As a more realistic challenge we have included here several transcripts that arose from the series of tests which took place at the Royal Society on 6th and 7th June 2014. These were originally presented in Warwick and Shah (2016). In those tests, the judges were told that one of the hidden entities was a human and the other a machine. However it was up to the judge involved in each case at the time, and now it is up to you, the reader, to decide which was which, based solely on the transcripts shown. The conversations are presented exactly as they occurred and the time given is exactly when each utterance occurred. The headings of the conversations indicate on which side of the computer screen the conversations appeared to the judge. Which entity was human?

In fact the entity on the left was a senior male human whereas on the right was the machine Eugene Goostman. The judge correctly identified the human, but decided that the entity on the right was also a human, even though the judge had previously been told that one entity was a machine and the other a human.

The conversation with the human entity on the left was relatively dull, being merely a case of question and answer with limited responses. Eugene did very well in this conversation considering it was interrogated by an expert on robotics who was familiar with machine conversations. The fact that Eugene convinced such a person is quite an accomplishment. You can see that Eugene tried to drive the conversation by asking the judge questions. At first the judge was not having any of it and simply ignored Eugene’s question, even though this was rather rude. Eugene persevered however and eventually the judge gave in and responded. Generally there was more content in Eugene’s conversation than in the one with the hidden human.

One aspect of the test is its reliance on the interrogators to do a good job. It is they who conduct and drive each conversation and who also decide which entity is the machine and which the human. Some researchers (for example Hayes and Ford, 1995) have suggested this is a weak point of the test. We, on the other hand, believe that it is a very important part of the test as Turing set it out. It is a test of humanness in conversation and it needs a human interrogator to be part of that. However here the quite direct question-and-answer interrogation appears to have failed to identify the machine. The next five-minute conversation is a little different. It was performed by a completely different interrogator. Again, which do you think is the machine?

The interrogator concluded that the entity on the left was a teenaged male human, non-native speaker of English. They were also absolutely definite that the one on the right was a machine. In this case the left entity was the machine Eugene Goostman whereas the one on the right a male human. So this was a clear case of a machine completely fooling the interrogator.

This second conversation was another in which the human’s conversation was the more dull. Eugene had a tendency to draw the interrogator to it, in contrast to the human entity. In fact the hidden human may not have done well for himself by claiming a lack of knowledge about the Turing test early on. Possibly incorrect conclusions can be drawn by interrogators based on an assumption that everyone must know a particular piece of information (Warwick and Shah, 2014). Thus, assuming every human knows a certain fact, then if the entity does not it must be a machine.

In this case, as the event was a Turing test session the interrogator appears to have had some quite strong evidence about the nature of the hidden (human) entity. It probably goes to show that you cannot rely on the knowledge base of humans. Indeed it is best not to try to make generalisations about the likely performance of humans in Turing’s imitation game, whether interrogators or hidden humans. Try your hand at the next conversation, which took place on 7 June 2014.

The judge concluded that on the left was a machine and felt that that entity exhibited very poor human-like conversation. On the other hand the judge was confident that the one on the right was a male human who was most likely an American. In fact the former was a hidden human whereas on the right was the machine JFRED.

The interrogator’s decision about the left entity was not particularly surprising. The hidden human was asked on more than one occasion for its name was to came the reply “I don’t know”. As a result the judge spent much more time conversing with the machine on the right. This is a particular aspect of the test that it involves a direct comparison between a machine and a human, rather than merely a machine conversing on its own. Here we can see that the hidden human involved was relatively uninteresting as a conversationalist and this might have helped fool the judge.

The above conversations are instances of the ‘parallel game’ in which a judge is making a decision about the identity of two hidden entities based on simultaneous question-and-answer interactions. In the one-to-one game a hidden entity is interrogated directly with no immediate comparison. This is an important difference for the interrogator and is one of the main features of the test.

Such a situation is, as you might guess, far different to the case when an interrogator knows for certain that they are communicating with a machine, as in the case of an online bot (Aamoth, 2014). Despite this point, for some reason there are a number of people who completely ignore this critical aspect of the test, go online to converse with a bot, which they already know to be a bot, and declare in conclusion that it is obviously a bot (Philipson, 2014). Clearly some education is required as to what the Turing test actually involves.

Anyway, see what you make of the next conversations which also occurred on 7 June 2014. Again a different interrogator was involved.

Once again in this conversation we see that the interrogator appeared to converse much more with one entity, in this case the one on the left, rather than the other. This is something that occurs fairly often. Both conversations lasted for five minutes although clearly the one on the left was fuller. The judge correctly identified that the left-side entity was a machine (Ultra Hal) but was unsure about the other entity, which was in fact an English-speaking male.

We hope that this chapter has served to give you a taste for what lies ahead. Possibly you were able to identify all of the entities correctly from the conversations

listed. On the other hand you may have found yourself agreeing with the interrogator, thereby making a few mistakes along the way. Whatever the case, it will be interesting to see your reaction to later conversations. Perhaps those that we have shown already will give you some pointers as to what to expect, what pitfalls to avoid and ways in which interrogators can get fooled.

Interestingly, when you do not have the answer in front of you it is not that easy to realise that you have actually been fooled. For example consider the actual case of a philosopy professor and his students who took part in nine actual Turing tests in 2008 and then wrote a paper (Floridi et al., 2009) where they state it was easy to spot which were the machines and which the humans in all the tests they had been involved with. In a later paper (Shah andWarwick, 2010) in the same journal it was, however, explained that the philosopher and his team had correctly identified the hidden entities in only five of the nine tests. In the other four cases they had, without realising it, misclassified humans as machines and machines as human!

What we do in Part One of this book is to have a look at some of the philosophy which underpins Turing’s imitation game, some of the background to his ideas and thinking and an indication of how the game has become such an important issue in the field of artificial intelligence. Finally we have a look at how conversation systems have matured over the years and how some of the first practical tests actually went.

Part Two is where you’ll find the results of our main series of experiments. These have involved a large number of human participants filling the roles of both interrogator and hidden human foil. At the same time we have been fortunate to work with the developers of the best conversation systems in the world.

Therefore we have devoted Chapter 9 to interviews with those developers in order to give some ideas as to what is important, and what not, from their perspective.

Three chapters (7, 8 and 10) cover in detail the three sets of experiments performed by the authors. In each case these required substantial organisation in order to bring together the best developers and their machines, with a large body of humans to act as interrogators and foils, networking specialists to realise a seamless and smooth operation, expert invigilators to ensure that Turing’s rules were followed to the letter by overseeing the whole process, and finally members of the public who were invited to follow the conversations and observe the judges in action.

The first set of experiments took place in October 2008 in Reading University, England (Chapter 7). These were in fact held in parallel with an academic meeting on the subject headed by Baroness Susan Greenfield and other well-known experts. As a result the participants were able to flit between the meeting and the ongoing tests. The second set of experiments (Chapter 8) occurred in Bletchley Park in June 2012 to mark the centenary of Alan Turing’s birth. Finally, Chapter 10 describes the series of experiments that took place in June 2014 at the Royal Society in London, of which Turing was a Fellow, to mark the 60th anniversary of his death.

But first of all we’ll have a closer look at Alan Turing himself and hear from some of the people who knew and interacted with him.

Turing’s Imitation Game: Conversations with the Unknown by Kevin Warwick and Huma Shah is OUT NOW.

Aamoth, D. (2014). Interview with Eugene Goostman, the fake kid who passed the Turing test. June 9, 2014. http://time.com/2847900/eugene-goostman-turing-test/.

Chomsky N. (2008). Turing on the “imitation game”. In: Parsing the Turing Test, R. Epstein et al., (eds). Springer.

Hayes, P. and Ford, K. (1995). Turing test considered harmful. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, Vol. 1, 972–977.

Floridi, L., Taddeo, M. and Turilli, M. (2009). Turing’s imitation game: still an impossible challenge for all machines and some judges – an evaluation of the 2008 Loebner contest. Minds and Machines 19 (1), 145–50.

Philipson, A. (2014). John Humphrys grills the robot who passed the Turing test – and is not impressed. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/bbc/10891699/John-Humphrys-grills-therobot-who-passed-the-Turing-test-and-is-not-impressed.html.

Shah, H. and Warwick, K. (2010). Hidden interlocutor misidentification in practical Turing tests. Minds and Machines 20 (3), 441–54.

Shah, H. (2010). Deception-detection and machine intelligence in practical Turing tests. PhD thesis, Reading University, UK.

Shah, H., Warwick, K., Vallverdú, J., and Wu, D. (2016). Can Machines Talk? Comparison of Eliza with Modern Dialogue Systems. Computers in Human Behavior. Volume 58, 278–295

Turing, A.M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind LIX (236), 433–460.

Warwick, K. and Shah, H. (2014). Assumption of knowledge and the Chinese room in Turing test interrogation. AI Communications 27 (3), 275–283.

Warwick, K. and Shah, H. (2016). Passing the Turing test does not mean the end of humanity. Cognitive Computation 8 (3), 409–416.

Latest Comments

Have your say!