During his travels through the southern states in 1854, Frederick Law Olmsted, a newspaper reporter for the New York Daily Times, visited a sugar plantation in southern Louisiana, where he was introduced to an enslaved man named William.

William was thirty-three years old, especially knowledgeable of local plantation agriculture and Creole culture, and, more importantly to Olmsted, he loved to talk. The bondsman was extremely “talkative and communicative,” the journalist noted with delight. Over the course of several hours the two men broadly discussed various issues of local and national interest, including sugar cultivation and even master-slave relations. Interestingly, however, the very first thing William said to Olmsted when they were introduced to each other was the seemingly irrelevant reassurance “that he was not a ‘Creole nigger’; he was from Virginia,” having been sold to Louisiana via the domestic slave trade when he was thirteen years old.

One might have expected “hello” or “pleased to meet you” to be the first words out of William’s mouth, and not “I’m not a Creole nigger; I’m from Virginia.” But not being mistaken for a Louisiana-born slave was obviously of profound importance to this forced migrant, despite the fact that he had lived in Louisiana for twenty years, learned to speak French fluently, and admitted no desire to move back to Virginia anymore, as he had already “got used to this country” and fully adapted to the “ways of the people.”

Yet however assimilated William may have seemed in the Louisiana slave society that had become his new home, cracks in his identity were clearly evident. He proudly continued to identify himself first and foremost as an outsider, a Virginian, even confiding to Olmsted his opinion that “the Virginia negroes were better looking than those who were raised here,” and that there “were no black people anywhere in the world who were so ‘well made’ as those who were born in Virginia.”

You could take a slave of Virginia, but you couldn’t take Virginia out of a slave.

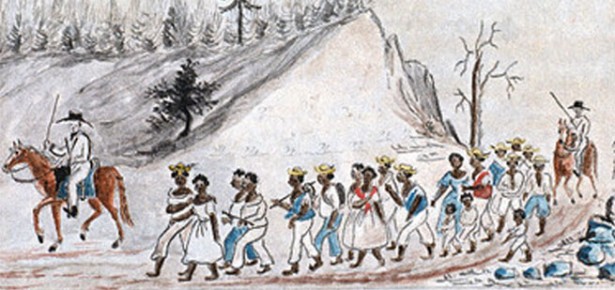

Slavery in the antebellum South was most strikingly characterized by one distinct feature: movement. Whether they were marched to other states in traders’ coffles, knocked off locally to new masters at public auctions, or hired out by the year to employers in southern cities, few enslaved people of what Ira Berlin has called “the migration generations” escaped the onslaught of forced migration.

Throughout the year the dusty roads and busy waterways of the South teemed with valuable black bodies changing places, changing jobs, changing homes. Almost a million were uprooted from the Upper South alone; washed across the continent to the new cotton and sugar plantations of the Deep South, they were permanently separated from their old communities.

What was it like for slaves to leave their homes behind and have to rebuild their lives somewhere else? Especially for those who, like William, were forced to move vast distances, to regions that may as well have seemed like foreign countries to them?

Imagine you’re William. You’re thirteen years old, a slave in Virginia. The year is 1821. You wake up one morning to find that, unbeknownst to you, your master has sold you to some strange man, a slave trader, who is now standing in front of your cabin, ready to pick you up and transport you to New Orleans. Without a moment’s notice you’re forced to take leave of your family and your home—the only home you’ve ever known—and you walk out the door, never to return. You are confused. You are out of your element. You are among strangers. And arrival in Louisiana only makes it worse. Auctioned off to a local planter, you are driven to a plantation where all the other slaves are Creoles and speak French, a language you’ve never heard before, and you’re put to work cultivating sugarcane, a crop you’ve never seen before.

How would you feel? How would you cope? How long would it take for you to make friends? How many years would pass before you called Louisiana “home”?

One of the central themes in this book focuses on the settlement processes of enslaved forced migrants, with a specific focus on the social and cultural adjustment involved in moving from one place to another. Many of us tend to assume that American-born slaves in the antebellum period shared a more or less homogenous culture and inherent solidarity, and that forced migrants adapted easily to local slave communities and made friends quickly upon arrival. But this was far from the case. Cast into new settings, newcomers often felt—and were treated by other slaves—like outsiders, and they were forced to utilize various strategies to effect their integration and forge new relationships. Mastering local accents and dialects (or in the case of those sent to Louisiana: languages) was an important strategy, for example, as were joining local slaves in religious worship, helping others in the fields, courting and marrying, and even collaborating with local slaves to steal food. The point is, it was a process. It took time. Migrants had to really work to carve out a place for themselves in new communities.

Like William, however, most enslaved forced migrants in the antebellum South continued to exhibit a “dual orientation” even decades after arrival. Never forgetting where they were from, they continued to identify strongly (and nostalgically) with their regions of origin and perceive themselves as intrinsically “different” from their fellow bondspeople in new communities. They talked a lot about “home,” passed on stories of their old communities to their children (whom they often named after loved ones left behind), and developed lasting friendships with other forced migrants from their home regions. When they met new people, the first words out of their mouths were often “I’m from Virginia” or “I’m from Maryland.” Somewhere in their minds, they never left.

Download free book excerpt from Slavery and Forced Migration in the Antebellum South

Latest Comments

Have your say!