Looking out from the barred window of his jail cell, John Anthony Copeland could easily see the rolling hills and agricultural lands that surrounded Charlestown, Virginia. There had been no opportunity for him to appreciate the beauty of the countryside since his arrival in the state only a little more than one week earlier. Now, in late October 1859, most of the abundant crops had been harvested, leaving the fields brown with rolls of hay and a few standing stalks of corn. The leaves on the native beech, oak, and ash trees, however, had already begun to turn red and gold, and the vivid colors might have cheered Copeland’s spirit if he had not been facing death by hanging.

While he reflected on ideals of heroism, martyrdom, and immortality, Copeland’s view of the outside world was bounded by the jailhouse walls

Copeland’s home was in Oberlin, Ohio, over 400 miles to the northwest, where leaves had already fallen and his mother and father longed for news of their imprisoned son. In time, he would write to his parents, assuring them of his belief that “God wills everything for the best good.” But for now, he had no words to calm himself or to bring them comfort. There was little hope for a black man charged with murder in Virginia, and even less for one accused of inciting slaves to rebellion.

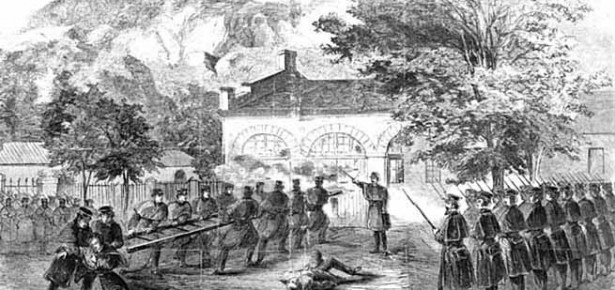

A mob had gathered outside the jailhouse, calling loudly for the blood of John Brown, whose abortive invasion of Harper’s Ferry had lasted only three days – October 16–18 – while taking the lives of four Virginians and a U.S. marine. Brown was already notorious from his days on the battlefields of “Bleeding Kansas,” but the four men captured with him – Copeland and three others – were unknown. That made no difference to the lynch mob, which wanted all of them dead. Nor did it matter to the Southern press, which dismissed all of Brown’s raiders as “reckless fanatics” and “wanton, malicious, unprovoked felons.” In fact, Copeland’s decision to join John Brown had been neither reckless nor unprovoked. Although only twenty-five, he had for many years been dedicated to abolitionism, having grown up among fugitives and freed slaves. As a child, he had evaded slave patrols in North Carolina and Kentucky; as a student, he had attended school with one of the former captives from La Amistad, who had been freed by order of the U.S. Supreme Court; and as a young man, he had confronted slave hunters and had spirited a runaway to freedom in Canada. In many ways, Copeland’s enlistment under John Brown’s command – far from an act of rash fanaticism – had been the culmination of his life’s progress from idealism to militancy.

Copeland’s motivation was also deeply religious. His parents had been known for piety in their native North Carolina, although the black churches they attended could never risk any open opposition to slavery. In Ohio, however, Copeland had been exposed to the evangelism of Reverend Charles Grandison Finney, the acknowledged leader of the Second Great Awakening and an avowed enemy of slavery. Finney preached in Oberlin’s First Church, which was one of the few fully integrated congregations in the United States and by far the largest one. Sitting side by side with white children, Copeland came to understand that his “duty to both God and man” required him to fight slavery, even if that might take him to “the dark and gloomy gallows.” For any man “to suffer by the existence of slavery,” he believed, was far worse than “the mere fact of having to die.” Copeland’s determination was bolstered by his powerful faith in the afterlife. He warmly accepted Finney’s promise that friends and loved ones would meet again in heaven. As Copeland himself put it, “when I have finished my stay on this earth . . . I shall be received in Heaven by the Holy God [to meet those] who have gone before me.”

Like many Southern “mulattos,” Copeland’s mother traced her ancestry to a Revolutionary War veteran, in this case General Nathanael Greene. And like many African-Americans in the North, Copeland himself idealized the revolutionary generation, believing that “those who established the principles upon which this government was to stand” intended the “right to life, liberty, and happiness” to belong “to all men of whatever color.” In Oberlin’s integrated school, he had learned to revere George Washington as having “entered the field to fight for the freedom of the American people – not for the white man alone, but for both black and white.” That was a familiar story in abolitionist circles, made no less inspiring by the fact that it was not really true. Although Washington had sometimes expressed support for gradual emancipation, he had freed no slaves in his lifetime and, as president, he had signed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793. Still, Washington provided a convenient hero for a young African-American who was prepared to embark on a revolutionary course of his own. He held fast to the belief that “black men did an equal share of the fighting for American Independence,” and the time had come for them to share the “equal benefits” they had been promised by the founders.

If Copeland’s veneration of George Washington was for the most part misplaced, his regard for another revolutionary era figure was fitting indeed. He identified closely with Crispus Attucks, who had been the first victim of the Boston Massacre in 1770. Copeland was proud that “the very first blood that was spilt” in the battle for American independence “was that of a negro,” calling Attucks “that heroic man (though black he was).” Attucks had been all but beatified by the black abolitionist movement, and Copeland shared the widespread admiration of his martyrdom. In Copeland’s words, Attucks had given his life for “the freedom of the American people,” which also marked “the commencement of the struggle for the freedom of the negro slave.” As he contemplated his own death, Copeland turned time and again to Attucks’s example of a black man whose memory endured long after his life’s end. He prayed that his own sacrifice would be recalled as proudly by his family and friends.

But while he reflected on ideals of heroism, martyrdom, and immortality, Copeland’s view of the outside world was bounded by the jailhouse walls. He could not even look in the direction of the Free states, as the only window in his cell faced cruelly to the south. With the shouts of the lynch mob in his ears, his thoughts turned to his years in Oberlin. It was the most thoroughly abolitionist community in America, where he had been nurtured, educated, and set on a path that led him to Harper’s Ferry as a soldier in John Brown’s insurrectionary army.

Download the full excerpt here.

Latest Comments

Have your say!