Image: Opensource.com via Creative Commons.

I’m lucky enough to have published many different books with Cambridge University Press – 14 altogether, counting those under contract. The vast majority are about my main scholarly passion: Creativity. These include two handbooks and volumes on how creativity is related to mental illness, neuroscience, cognitive development, different domains, writing, the classroom, and personality.

Indeed, The Psychology of Creative Writing hints at my childhood dream: to be a creative writer myself. I debated getting my MFA in Creative Writing, but I still remember writing to one school for information and being told that every year they graduated 20 MFAs and every year there were a total of 25 jobs in the country for MFAs. If you can do anything but write, they said, do that. I could imagine doing something else – namely, psychology, so I ended up getting my Ph.D. in Cognitive Psychology at Yale with Robert Sternberg.

In the meantime, though, as I stumbled through my Ph.D., I still wrote. I wrote all sorts of plays – ten minute plays, one acts, the occasional full length, and a musical. This was the early days of the internet and I put all of my plays on-line, and they were produced a number of times at tiny theatres and colleges and high schools around the country. The musical, Discovering Magenta, was my baby. It was about a mental health worker trying to help a catatonic patient handle the demons in her past. I teamed up with composer Michael Bitterman and he taught me all about how to write lyrics and structure a song. We recorded a demo CD, submitted it, and waited. Right away, we had interest – and two potential productions fall through. Then I got my Ph.D. And I started full-time work. And I met the woman who would become my wife. And I got distracted.

I don’t know why I stopped writing plays. I had much less time, particularly with so many books on my plate (and once the kids joined our family, infinitesimally less time). A lot of my plays revolved around people looking for love or their way in life. Now that I was feeling more certain of my own place in the world, I felt a little stuck at what I wanted to express. But I also wonder if there was more than that. Writing a play represented a risk. I could invest time and energy into a play and there was no guarantee that anything would come of it. But any article or book about creativity I get published pretty easily. I get complimented for it. I sometimes even get a little bit of money.

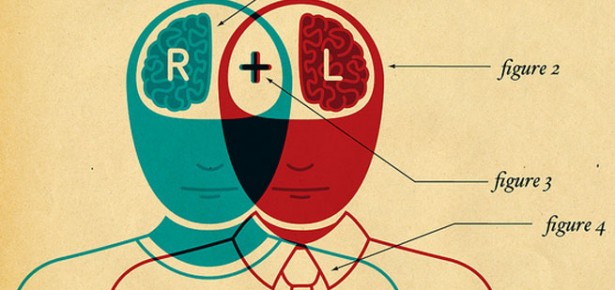

In psychology, there is a lot of talk about intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivation.

Intrinsic is doing something because you love it, and extrinsic is doing something for other reasons – money, praise, rewards, etc. I felt intrinsic motivation to write plays and doing psychology, but I was only getting the extrinsic rewards for psychology. As much as I teach and write about the importance of intrinsic motivation (especially for creativity), it’s kind of nice to have your work seen by people. There’s no shame in praise or money.

This spring, my composer Michael told me he submitted our musical to the Thespis Festival in NYC and it was accepted. This wasn’t the “rich and famous” contract that the Muppets signed; we’d have to produce the show, and it would only be for three performances, and there is every likely chance that there isn’t a producer waiting in the wings. But – it means life for the show. It means that maybe another theatre (anywhere) might pick it up or be interested. It means a chance. So we are getting to go up in early September, with the amazing Valeria Cossu as our director.

As much as I talk about creativity (and I talk about it a lot), it’s only been in the last year that I’ve realized just how much guts it takes to be creative. There’s a stigma in being creativity, perhaps because of its (overinflated) association with mental illness (as various essays discuss in Creativity and Mental Illness).

I think about how creativity fits into our lives. I’m lucky enough to use my creativity at work – as I get ready to mount this play, I am also preparing the second edition of two books for Cambridge and working on two new ones. But my playwriting creativity is a different beast – a different feeling, something rougher and scary and thrilling. I have no illusions that I could ever be a fulltime playwright (nor any particular desire). This creativity is for evenings and weekends. It’s what I fall asleep thinking about and what pops into my head while driving to work. I used to only want to do something if I could be the best at it, or at least “Pro-c” (an expert creator). Now I don’t mind not being great – but at the same time, I also know I couldn’t go back to writing if it would never get produced.

We don’t study “hobby” creativity much – we tend to focus on creativity at work or school, or everyday creativity or genius creativity. What drives people to be creative in their spare time? What do they want from it? I’m slowly starting to find out. Perhaps it will be my next Cambridge book.

Latest Comments

Have your say!