The mother of a friend of mine recently lost her husband to a massive heart-attack. Margaret is a poised and elegant professional woman, but I remember a very moving conversation we had not long afterward. I was telling her what I’ve learned about mourning for this book: that people in grief often feel cut off from their community. They are do not fit the social boxes in which they used to live. Other people don’t know any more how to talk to them or be with them. Margaret nodded emphatically, and I could see that for her this was another loss, one she had not anticipated.

The mother of a friend of mine recently lost her husband to a massive heart-attack. Margaret is a poised and elegant professional woman, but I remember a very moving conversation we had not long afterward. I was telling her what I’ve learned about mourning for this book: that people in grief often feel cut off from their community. They are do not fit the social boxes in which they used to live. Other people don’t know any more how to talk to them or be with them. Margaret nodded emphatically, and I could see that for her this was another loss, one she had not anticipated.

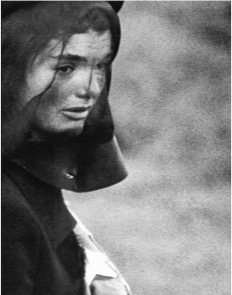

In this way, I think that people who mourn are very much like those who have died: cut off, alone, in some kind of limbo, in certain ways invisible. This is the central insight of Grief and Women Writers in the English Renaissance: that in an era when people didn’t quite know where the dead were, their mourners were likewise in a kind of limbo.

For women writers of four hundred years ago, writing about grief was one of the ways to have a writing voice: even when it was difficult to be a public figure as a woman, it was permissible to write as a mourner.

Mary Sidney Herbert, the Countess of Pembroke, published her poems and translations in memory of her famous brother, Sir Philip Sidney, killed in battle. She dedicates her work to her brother, but she also imagines herself and her poems broken, incomplete, and torn, like him.

Aemelia Lanyer, married to a court musician and mistress to a royal courtier, was an entrepreneurial writer in need of aristocratic women patrons. In her epic on the crucifixion of Jesus, Lanyer flatters w omen readers by suggesting and she and they are all virtuous Christians because they sympathize with Jesus at his crucifixion. Women are all like Jesus, she says, because they share his pain.

omen readers by suggesting and she and they are all virtuous Christians because they sympathize with Jesus at his crucifixion. Women are all like Jesus, she says, because they share his pain.

Mary Wroth is Mary Sidney’s niece; she writes nostalgic poems and romances which are full of weeping characters and melancholy moods. In her poems, she loses herself as well as her lover in the same imagined sorrow.

Katherine Philips, the last of the writers in my book, writes during a period of civil war, at a time when mourning the wrong person could lead to real trouble. Philips in her poems is very careful to write elegies for, and make alliances with, political martyrs on both sides of the conflict.

These four women do use their tears as a way to speak to the world. But what they also realize is that they are identified with those they mourn—that they are both powerful and invisible, a bit like ghosts themselves. These women writers working in Shakespeare’s and Milton’s England know that their mourner’s voices are also the voices of the dead themselves: veiled, mysterious, and exiled. That they each find ways to use this invisibility is part of what makes them artists.

Latest Comments

Have your say!