If you want to know about how we deceive others, and even more intriguingly how you deceive yourself, I would ask you to read my forthcoming text: Hoax Springs Eternal: The Psychology of Cognitive Deception. For it is in this book that I have tried to illustrate the founding psychological process which are examined, discussed and exemplified so that you can avoid being deceived by others and, more importantly, avoid deceiving yourself. Decisions about deception are a critical element of all decision-making processes. Such processes are frequently divided into two general categories. One of these processes happens rather quickly and depends a lot upon our implicit knowledge. Fast, accurate decisions often characterize real-world experts. This capacity has been referred to as recognition-primed decision-making. Often, people don’t know exactly how they know what they know; they just know they know it! In contrast, rational decision-making is much slower and more deliberative. It is the kind of decision-making that happens when you put all of your options on the table and have plenty of time to compare them so that you can make an important, conscious decision (imagine something like buying a house or a new car). Here, the facts are clearly laid out and you consciously look to balance one factor against another in order to derive your final choice.

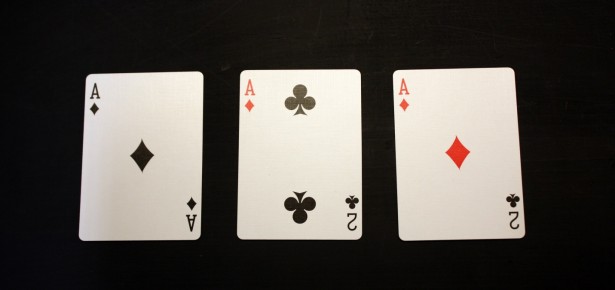

Now imagine that someone is trying to deceive you when you are using these two respective processes. On the one hand you have fast, ‘sleights of hand’ in which the speed of the hand deceives the eye of those engaged in recognition-primed decision-making. Well, really it’s not quite as simple as that. Speed is only one of the dimensions of such deception; importantly, capacities such as perception and attention must also be manipulated. The deceiver here must understand and play on people’s natural assumptions that make us all believe we are ‘experts’ in some realm or other. Let’s consider a simple example. The majority of us, having played cards, ‘know’ that the suits hearts and diamonds are red and that the suits spades and clubs are black. We also know that what appears in the top left of a card is also replicated in the bottom right of a card. It is part of our world knowledge and our ‘card’ expertise. The deceiver also knows this, and plays heavily upon our assumptions that, being implicit, fly past us without entering conscious attention. The illusion is embedded within our perception of familiar items, founded in our long-term memory and the sorts of cognitive short-cuts that reduce the need for too much everyday thinking. Playing on assumptions is the deceiver’s stock-in-trade. He or she can use cards of the type shown below to weave their deception (and be assured you will not be allowed many minutes or hours to inspect all of the associated paraphernalia) for to do so will unravel this type of deceit rather quickly.

Deceiving the eye can be fun; it is the basis of much of what we consider ‘magical’ entertainment. These deceptions require a complex understanding of human sensory, perceptual and attentional capabilities. However, there is another (and in my view) rather more fascinating side to deception. This involves deceiving the mind. Here, the fairly simple tactics of attentional misdirection and distraction are much less in play. Often, the source of the deception is a physical (or in the case of cyber-deception) an electronic representation. This object or entity is placed before you for your careful deliberation. In the stories and case studies that I present in my book, these are represented by fixed objects; there is no magician or deceiver present to help the case when awkward issue come up. These deceptions must stand alone. Here, much more complex elements of cognition come into play. Decisions and deceptions here are colored by emotion, by the various biases to which the human is heir to. They present puzzles, posers, teasers, conundrums, which ‘force’ the invested individual to commit to one side (fake) or (true) the other. Rational ‘fence-sitters’ often get short-shrift in the welter of arguments around what these, emotion-provoking entities are. My book is all about these various psychological processes and how we can see them at play in the six famous cases I have chosen to feature. These are: the Map, the Plate and the Bone, the Shroud, the Cross and the Stone. But beyond even these fascinating stories lies the rather darker question of how and when we deceive ourselves. Do we deceive our own decision-making what happens when we do? Thus, this is not a Handbook for Deceivers; it is an appeal to undeceive ourselves. I hope that you will enjoy trying to do that.

Latest Comments

Have your say!