AP

Protests in the United States resulting from recent grand jury decisions to not indict white law officers who used deadly force against African Americans have prompted national discussions about racial disparity in law enforcement and court proceedings.

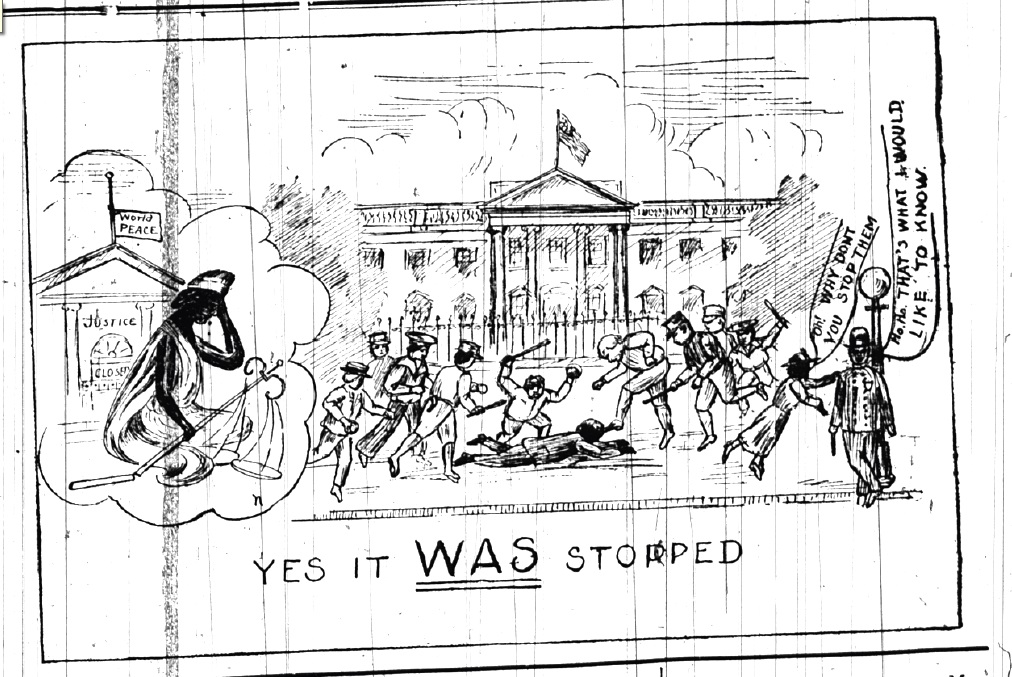

This cartoon, published in the Washington Bee, a black weekly, highlighted a major problem during a riot in the nation’s capital in July 1919: police failed to stop white mobs from attacking African Americans. “Oh! Why don’t you stop them?” the woman on the right asks. “Ha, ha. That’s what I would like to know,” the officer replies. According to another Washington, D.C., newspaper, a police officer actually said this to an observer during the riot.

Again. In its 1968 report on the urban uprisings that broke out across the U.S. during 1967, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders noted the “widespread belief among Negroes in the existence of police brutality and in a ‘double standard’ of justice and protection—one for Negroes and one for whites.” Many contemporary commentators refer to this recent history in their analysis of the protests against the outcomes of grand jury decisions in St. Louis and New York City. I’d like to go back further in U.S. history to offer another comparison. My book, 1919, The Year of Racial Violence, is a study of how African Americans mounted a three-front campaign—in the streets, in the courts, and in the press—to defend themselves against mobs, unjust police practices, and biased court proceedings in 1919, one of the worst years of racial conflict in U.S. history.

To understand 1919’s relevance to our time, it’s helpful to first point out the biggest difference. Just after the First World War ended, dozens of white mobs formed to attack—and often lynch—African Americans who asserted their equality with whites. These assaults took the lives of approximately 250 Americans, most of them black, and engulfed ten U.S. cities in civil disorder. Chicago’s riot, one of the worst, lasted a week, killed 23 African Americans and 15 whites, and required the deployment of more than 6,000 state militia to restore peace. In another 1919 riot, in Phillips County, Arkansas, a white posse and federal troops killed at least twenty-five African Americans—one estimate puts the black death toll as high as 100. During each riot, African Americans undertook armed self-defense measures that deterred many attacks, preventing the casualties from increasing.

Mobs aren’t forming to attack African Americans today. But violence directed against blacks was only one part of 1919’s conflict. During the riots, police forces struggling to restore law and order often unjustly targeted African Americans, especially those who had to take up arms to defend themselves. In Omaha, Nebraska, police charged blacks with carrying concealed weapons but didn’t arrest whites for the same offense. In Washington, D.C.’s riot, police failed to stop white mob attacks on African Americans but they arrested blacks who defended themselves, and, in some cases, brutalized them. A black resident who visited his local precinct observed almost thirty police officers beating and kicking a black prisoner. “I rushed through the crowd and standing over the man demanded that these officers treat him as a man and a human being,” he stated afterward. Very few African Americans served on Omaha’s and Washington’s police forces, a fact that reinforced black residents’ view of the police as hostile and biased. Meanwhile armed white rioters received preferential treatment. During Chicago’s upheaval, a police officer released several white rioters from a jail cell and returned their weapons, commenting, “You’ll probably need [these].”

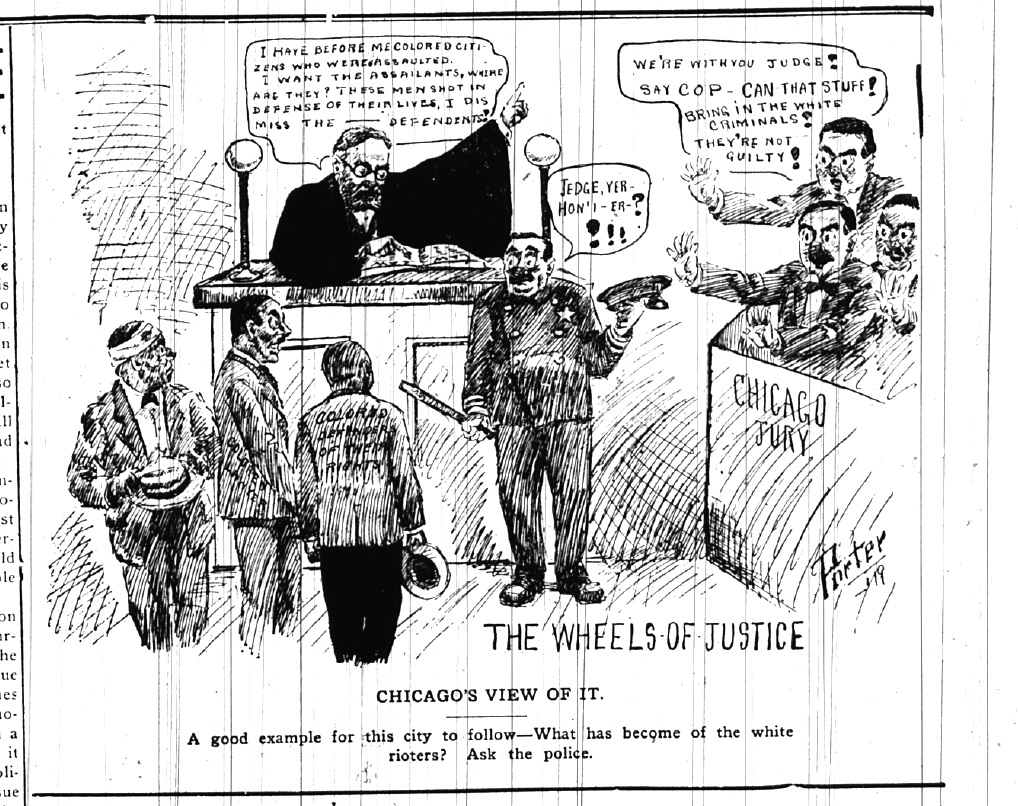

Also published in the Washington Bee, this August 1919 cartoon denounced the decision of the Illinois state’s attorney to only indict African Americans (many of whom had defended themselves against mob attacks) after Chicago’s 1919 race riot. Evidence of white crimes against blacks collected by the NAACP led the grand jury in Chicago to go “on strike” until the state’s attorney presented cases against white defendants, an action also referenced by the cartoon.

One-sided law enforcement carried over into the courts. The number of arrested black men in Washington far outnumbered white men, even though whites were the majority of rioters. African Americans quickly mobilized to counter this bias. The Washington, D.C., chapter of the NAACP dispatched experienced black attorneys to the courtrooms. These men, who included prominent Howard University Law School faculty, won many acquittals or convinced prosecutors to drop charges against African Americans who had defended themselves during Washington’s riot. A black minister appealed directly to Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who instructed a prosecutor, “it goes without saying there ought to be no discrimination of that character.” In response to the Illinois state’s attorney’s decision to only seek indictments against black defendants, Walter White of the NAACP gave evidence he had personally collected of white crimes against blacks to the all-white grand jury in Chicago. As a result, the grand jury went “on strike,” refusing to hear additional cases until the state’s attorney also began presenting charges against white defendants. The legal defense of Arkansas sharecroppers falsely accused of a conspiracy to murder whites produced an important 1923 Supreme Court decision, Moore v. Dempsey, which ruled that the federal government must require the states to uphold due process and equal protection of the laws in their own courts. Although these legal efforts did not fully right the scales of justice, they did free many unjustly charged African Americans and drew national attention to prejudiced police practices.

What insight do these events from 1919 offer us today? By one measure, the United States has vastly improved its policing practices—it’s hard to imagine today’s law enforcement officers standing idle as mobs attack citizens. But when encounters between white police officers and black citizens escalate into violence, for whatever reasons, the long, troubled history of relations between majority white police forces and majority black communities can’t be ignored. The challenge before the nation isn’t an easy one to overcome: how can police and prosecutors convince Americans of color that enforcement of the law, in the streets and in the courts, is applied impartially? During 1919, disappointing outcomes during the first set of court proceedings did not deter black attorneys and the NAACP from filing appeals, collecting and presenting evidence, and going all the way to the Supreme Court. If the grand jury procedures currently used to review police use of deadly force are in need of revision, then one lesson of 1919, the year of racial violence, is clear: it’s possible to make these changes.

Latest Comments

Have your say!