As a cell biologist, I am fascinated by clones. These are populations of cells arising from a single progenitor. Cells are defined as members of a clone because they share at least one genetic marker.

As a student, I studied clones of antibody-forming cells. This was at a time when other workers first identified rearrangements of antibody genes as highly specific genetic markers of individual clones active in the processes of immunity.

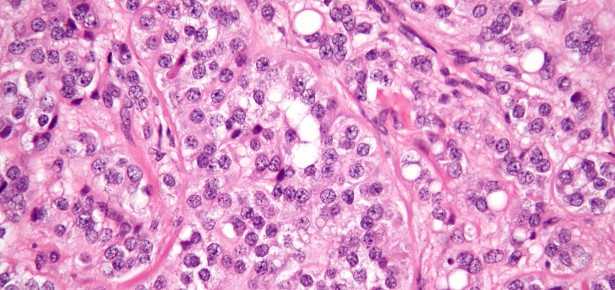

I progressed to cancer research. Cancers too are known to be clonal. Very often, all the cells in a cancer share one or a number of distinguishing mutations. The millions of cells all possess each such defining mutation because they inherited it from the one founding cell in which the mutation arose. The history of a cancer is now described by the sequential appearance of new mutations, and the sequential development of new sub-clones.

Imagine my amazement when, reading as a cancer cell biologist, I came to realise that multiple species also share genetic markers that define them as clones. Groups of related species may be shown to be descended from one individual cell in which a defining shared mutation occurred. This insight came directly from my involvement in cancer biology: the principles describing cellular and organismic evolution are the same.

I read with mounting fascinating how humans share millions of genetic markers with chimps and the other apes. These species are thereby shown to be clonal, for each of these genetic fingerprints arose as a unique event in one reproductive cell from which all living apes are descended. We share a sub-set of these markers (still a large number) with Old World Monkeys. Apes and monkeys are clonal too. More remotely in time, all primates are clonal. More ancient clones can be identified linking us to rodents, cats, and elephants.

Biologists do not normally describe primates or mammals as monoclonal groups of organisms. They use the term monophyletic to indicate that all primate or mammalian species are linked to common ancestors.

Sheer fascination was one motivation that led me to document this history in a book, Human Evolution: Genes, Genealogies and Phylogenies. I thought that as a cancer cell biologist, I could inspire others with the wonder of the new genetics and with what it showed about the dramatic epic that is biological history. Our own DNA is a record of our family history. The genetic information recoverable from the DNA found in a hair links us to all other mammals.

But there was a second motivation. I had been aware that many people find evolution threatening. It has been given all sorts of metaphysical connotations. The issue has become confused and contentious. But I have stressed that evolution is a strictly scientific idea and it is studied by strictly scientific approaches. It should not carry metaphysical baggage.

Controversy between any branch of science and Christianity is unnecessary. For Christians, biological history – any history for that matter – is a part of creation, which is in its entirety open to scientific investigation. The forerunners and founders of science, many of whom were theologians, recognised that the concept of creation legitimated untrammelled research into physical reality.

Latest Comments

Have your say!