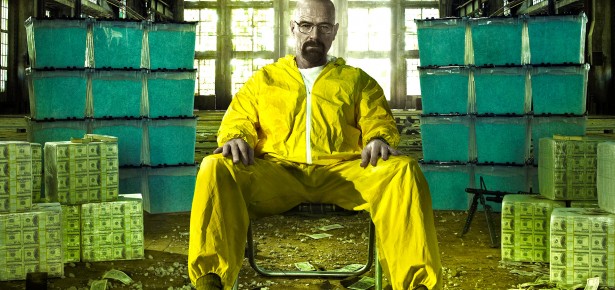

Image Credit: AMC Networks

Recently Breaking Bad picked up two awards at the Golden Globes ceremony in Los Angeles, which is impressive for a series featuring a school teacher turned crystal-meth drug manufacturer happy to turn his hand to murder, all in the name of providing for his family. By now, though, this has become something of a recognisable figure in American television drama. Consider Tony Soprano, Mafia boss and family man, who combined a trip with his daughter to a prospective college with strangling an informer, or the characters in The Wire, or Mad Men, all reaching for a version of the American dream while unsure who exactly they are and what that dream may consist of. The existential anti-hero has emerged as a central character, though there is a line of descent from Jay Gatsby, for whom Don Draper in Mad Men is obviously a paradigm. The fear these characters have is that it may all be for nothing. As Tony Soprano’s vindictive mother, Livia, remarks, life is ‘all a big nothing … don’t expect happiness … in the end you die in your own arms.’ As Tony himself observes, ‘I’m not afraid of death … not if it’s for something.’ The question is what that might be.

Something, it seems, is going on in the American psyche which is perhaps why so many series feature psychiatrists (see also Six Feet Under and In Treatment). For David Chase, creator of The Sopranos, ‘The kernal of the joke … was that life in America has gotten so savage … basically selfish, that even a mob guy couldn’t take it any more.’ The mobsters ‘invented “it’s all about me” – and now he can’t take because the rest of the country has surpassed him.’ The ethic of the Mafia has become the ethic of the country.

This, indeed, is what is so fascinating about these and other series. American long-form television drama, long dismissed by those for whom European public service television held the exclusive rights to producing such series, engaging with private and public issues, has, for more than a decade emerged as something more than a worthy rival. At a time, too, when Hollywood has largely given itself over to plot-driven CGI extravaganzas, television has become the place where writers (novelists, screenwriters, journalists) wish to work. Largely, though not exclusively, because of the emergence of cable television it began to be possible to produce work that did not depend on ratings, growing audiences through the sale of DVDs and subsequently through streaming, webisodes, active web sites.

The Wire took on the deprivations of American cities, the failures of education, government, the media. Battlestar Galactica engaged with the political, social and moral impact of 9/11. Mad Men explored the ambivalent attitude towards women and racial minorities in the 1960s but with continuing relevance in a country in which debates over personal and national identity never cease.

Audiences, meanwhile, apparently, have no difficulty in identifying with these ambiguous figures, though it is hard to believe that a certain disturbance of moral equanimity might not ensue. The West Wing presented an idealised version of an American president but one capable of lying to the American public and authorising an extra-judicial killing. Dexter features a serial killer who is also a cop. 24’s Jack Bauer tortures, with the express permission, and on one occasion in full sight of, the President at a time when the real President was authorising and justifying just such actions.

American television drama, then, is today not only characterised by exceptional writing and acting. It also offers a remarkable insight into America itself.

Latest Comments

Have your say!