The advance blurb for your book ‘A Jacobean Company and Its Playhouse’ claims it ‘fills a major gap concerning the world of Shakespearean drama’. Since it is about a company other than Shakespeare’s, how can this be true?

The Queen’s Servants were a company of actors – many of them friends and rivals of William Shakespeare’s during Elizabeth I’s era – who were allotted the patronage of the new king’s wife when James Stuart came to the throne. As a model for understanding companies of Shakespeare’s time, there are many more documents available covering the history and workings of this company compared with those of the King’s Men (Shakespeare’s). Through this book, therefore, we can understand in some detail how companies and playhouses worked at this essential period for the development of entertainment. It has also been a missing history, and therefore an absent piece of a considerable puzzle.

It has taken sixteen years to put together effectively, because the materials which make it up are so rarely used in any context – and so disparately found. The story is also important to present as responsibly as possible for a much-desired, more complete picture for Shakespearean theatre history.

Which are the company’s actors who knew Shakespeare in this book? Can you tell us more about them?

Unlike the Globe or the Blackfriars, the Red Bull survived anti-playhouse edicts and went on to be the venue for surreptitious forbidden performances throughout the Civil War and the Interregnum

Two important players may be pointed up as Shakespeare fellows (although there were more): Will Kemp and Christopher Beeston.

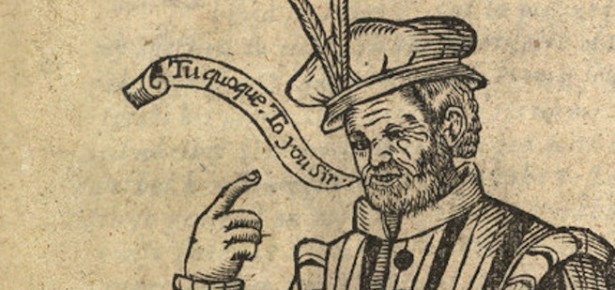

Kemp was the clown who created parts like Dogberry in ‘Much Ado About Nothing’ and Peter in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. He is thought to have improvised too much and was, perhaps, too popular for Shakespeare’s Chamberlain’s/King’s Men. He turned his back on the Globe and its riches and moved to the book’s troupe in the early 1600s.

Perhaps the most significant of the two, however, was Beeston, who was to build the Queen’s Servants’ indoor theatre, the Cockpit-Phoenix, in 1616. This was the first playhouse to be built in the Drury Lane area of London, thus the earliest representative for what we know today as London’s ‘West End’. Beeston worked with Shakespeare when he was a teenager. Who knows – maybe he created or developed the parts of Romeo or Juliet or Mercutio – or even Hal for the Chamberlain’s Men. If he achieved some kind of celebrity status early on it would certainly explain his over-confident behaviour described in the book – and his provable power – as the seventeenth-century entertainment industry continued.

So this company went indoors in 1616 like the King’s Men in 1608. Can you tell us more about the Cockpit-Phoenix?

Note: I say this 1616 playhouse was built in the Drury Lane area of London – between Drury Lane and Wild Street – adapted/rebuilt from cockfighting buildings. Indeed, the new ‘Indoor Jacobean’ or ‘Sam Wanamaker Playhouse’ currently being built adjoining ‘Shakespeare’s Globe’, is based on designs which were once thought to be for the Cockpit. The style of these designs, alongside the relationship between Anna of Denmark, the company’s patron, and Inigo Jones, her masque-designer, meant it was believed these were Jonesian plans for this playhouse. There are disagreements concerning this today. Some scholars say that these are not by Jones at all but by his pupil, John Webb – drawn at a later date – and were probably never built at all. What we do know is that a year after the company moved West, this playhouse was damaged in a Shrovetide riot, and had to re-open later as the ‘Phoenix’ – figuratively rising from its ashes…

What of Thomas Heywood, the playwright most associated with this company’s work?

Shakespeare was the central actor-playwright for the King’s Men in the same way Heywood was for the Queen’s Servants. Heywood and Shakespeare were on parallel planes and kind of unique in this respect. It is important to remember that both men were actor-sharers of their companies. Without being actors they could not be sharers of certain profits achieved at the door. It sounds obvious to say, but profits could only happen if audiences came to see the plays. This was the direct incentive for good-quality plays written by actor-sharers. They had to be good for money to change hands so that the company of players could live and continue to work. There is evidence that Heywood did his best to promote the profession of playing as a respectable one, particularly with his Apology for Actors (published in 1612). All this is elaborated upon in this book – as well as analysis of a number of Heywood plays as Queen’s Servants/Red Bull products.

How respectable can we actually say these actors were? Gerald Eades Bentley, for example, discussed the playhouse’s ‘Reputation’ at some length in his seven-volume Jacobean and Caroline Stage. Did these problems not include the actors?

It is certainly true that indexed in this book – under the terms ‘crime’ and ‘the Red Bull’s actors and associates’ – pages are entered covering ‘bigamy’, ‘defamation’, ’embezzlement’, ‘manslaughter’, ‘rape’, ‘theft’ and ‘wounding’. Accusations exist of them harbouring criminals and involved them playing a part – on the periphery at least – of the sex trade. As I write in the Introduction, the playhouse certainly was ‘an exciting and excitable place’. However, I also issue with Bentley and his will to judge the early reputation of the Red Bull with evidence based on events mostly taking place after the company’s time at the playhouse. Where the ‘exciting or excitable’ does occur for the Queen’s Servants moreover, it is on occasions where accusations are plentiful, but convictions are few. The Queen’s Servants at the Red Bull were an outfit much maligned from their own period onwards. This book sets about giving facts and – hopefully – not too fixed an interpretation of them at the same time.

Your book sounds a busy one, yet you only take the history up to 1619 when Queen Anna died. What happened to the Red Bull after this?

Perhaps the most important thing to remember about the Red Bull playhouse itself was its longevity. Unlike the Globe or the Blackfriars, the Red Bull survived anti-playhouse edicts and went on to be the venue for surreptitious forbidden performances throughout the Civil War and the Interregnum. In fact, it went on to see performances into the Restoration period. Samuel Pepys records visits in his Diary. Information using evidence from these periods are only used in the book where the research helps us to understand what the building etc. of the Red Bull was like. Quite why it lasted for so long is not really known. It might have been to do with the materials the playhouse was made of – possibly brick rather than wood at a certain point – or it may have been to do with the people who were fundamentally responsible for the site: the Seckfords, the Bedingfelds and the ongoing Woodbridge/Seckford charity.

Your blurb mentions these families and their associations with the site. Who were these people?

Author and Historian, Dr Eva Griffith. Photo: Matt Jamie.

The Seckfords and the Bedingfelds supply us with serious angles over and above a simple interest in early drama. They show the study’s roots firmly planted in Clerkenwell, yet stretching as far south as the Bankside and the royal courts and as far north, at least, as East Anglia, where the rents for the playhouse were intended to support poor people in Suffolk. Horses, stuffs for hunting and royal progresses were the work arenas of Sir Henry Seckford and Thomas Bedingfeld. They were both associated with the Revels Office located not far from the Red Bull – a playhouse built on the ‘Seckford Estate’, a charity set up by Sir Henry’s brother. Bedingfeld translated a recognised source for Shakespeare’s ‘To be or not to be’ speech from Hamlet. He was also related through marriage to the playhouse’s landlady – a brewer’s daughter. There is a picture of Anne Bedingfeild in the book, and for anyone interested in any combination of Theatre, women-and-theatre, Reformation, and land development, I would direct their attention to the early chapters of this book.

What of Anna of Denmark, the patron of the company? How did the repertoire of these players appeal to her and her family and associates?

The repertoire did not just appeal to Anna’s family in England. There are traces proving that elements of the company travelled to the European courts, including those of Anna’s blood-relatives and performed recognisably Red Bull plays there. Evidence is sparse when it comes to performances by the Queen’s Servants at the English court, however, and the book goes into theories about why this should be. Much centres on Sir Robert Sidney, Baron Sidney of Penshurst, later Viscount Lisle, later earl of Leicester. He was Queen Anna’s Chamberlain and would have been responsible for her entertainment. Some of the repertoire’s plays were certainly women-interested, particularly the extraordinary Rape of Lucrece by Heywood and the anonymous (but unforgettably entitled) Swetnam the Woman-Hater Arraigned By Women. There are also many spectacle-orientated plays which would be foolish to ignore in relation to Anna, and many masque-like elements, of which we know she and her circle were fond. At least one of her ladies owned a residence on the Seckford Estate from before the Red Bull was built there, and many court personalities – including others linked to Anna – possessed associations with Clerkenwell.

You say you supply a missing history, but in ‘advance praise’ of this book, Andrew Gurr states that you replace a scholar called G.F. Reynolds. What is your perspective on Reynolds?

Of course, in the area of Shakespearean theatre history – and the practice today of re-living it in similar performance spaces – I was delighted to be endorsed by Professor Gurr. George Fullmer Reynolds used stage directions and clues from published plays of the Red Bull to give an idea of what the staging was like. He rightly assessed that the known repertoire could provide a model for imagining other playhouses and was in advance of his time in this way. Now that we have a more detailed picture, however, there is so much more to say. In his time Reynolds possessed the barest of facts about the company and nothing of the Red Bull’s physical provenance. All that is currently known is given here, however, including the actors stories, touring records, all the theatres the repertoire came from, and maps, surveys, plans and portraits.

Is there anything else you think we should know about your book on the Queen’s Servants at the Red Bull?

Here we have only scratched the surface when it comes to, for example, the company history from when they were the Earl of Worcester’s Men onwards. The Queen’s Servants’ history mainly comes in two chapters at the end of the book and is, in many ways, of itself confusing because of the company’s complex problems. The story is quite sad (from our lucky standpoint) as we learn of many deaths in the company’s families, for example. But most of the actors went on as the Revels players, one of them a lauded player called Richard Perkins who, like others, turned his back on opportunities with the King’s Men. Another, Robert Leigh, who we learn about in fits and starts (through court payments and other records), was prominent in English tours and court cases. He was obviously an established, senior member. There is a great deal to learn about – and a great deal to improve – for a better and better understanding for theatre research to come.

Dr Eva Griffith is the author of A Jacobean Company and its Playhouse (2013). She is a theatre historian working on early seventeenth-century entertainment, spectacle and drama. She began acting at the age of seven, performing in many film, television and theatre productions. Owing her entire existence to the performance of Shakespeare (her parents met during an Old Vic touring production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream), she was encouraged in an interest in literature and history through united family concerns.

Dr Eva Griffith is the author of A Jacobean Company and its Playhouse (2013). She is a theatre historian working on early seventeenth-century entertainment, spectacle and drama. She began acting at the age of seven, performing in many film, television and theatre productions. Owing her entire existence to the performance of Shakespeare (her parents met during an Old Vic touring production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream), she was encouraged in an interest in literature and history through united family concerns.

Latest Comments

Have your say!