Courtesy of Warner Bros.

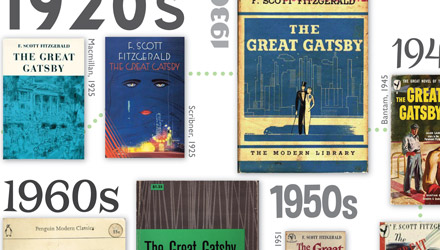

We’ve been hearing a lot lately about Baz Luhrmann’s new Great Gatsby film and an unexpected source that helped inspire it—Trimalchio, an early version of the novel that F. Scott Fitzgerald submitted to his publisher a year before the Great Gatsby manuscript. Long dismissed as an early draft, Trimalchio remained unpublished until 2000, when Cambridge University Press published an edition that remains the only one on the market today.

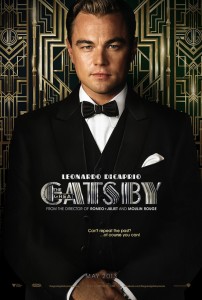

Now, I’ve never been a huge fan of Fitzgerald—I read The Great Gatsby once in high school and never felt the need for another go-around—but as a girl who grew up in the 1990s, I am a huge fan of Leonardo DiCaprio. So when they rolled out the trailer for Luhrmann’s glittering 3D adaptation, I started gearing up for the “summer of Gatsby” it promised.

I am a dedicated believer in the adage that the book is always better than the movie (I make exceptions only for The Godfather and Jaws), so I decided to give The Great Gatsby another chance. While I was rereading, I figured I’d also flip through the story it started out as, and I ordered a copy of Trimalchio.

They make a great pair: Trimalchio is more similar to the final novel than I had expected, but the differences are startling. Leonardo DiCaprio told the Los Angeles Times that Trimalchio made Fitzgerald’s “intent shine more clearly through,” which made it “like a bible…on the set” of the film. His performance is rumored to draw on the more mysterious Jay Gatsby of the early version, whose shady backstory and rise to fortune is not revealed until the very end of the novel, so that the rumors of espionage and murder swirl around him go unchallenged and Gatsby starts to look very suspicious. Trimalchio’s Gatsby is also angrier and darker, which becomes clear in the climax of the novel when he argues with Tom Buchanan.

They make a great pair: Trimalchio is more similar to the final novel than I had expected, but the differences are startling. Leonardo DiCaprio told the Los Angeles Times that Trimalchio made Fitzgerald’s “intent shine more clearly through,” which made it “like a bible…on the set” of the film. His performance is rumored to draw on the more mysterious Jay Gatsby of the early version, whose shady backstory and rise to fortune is not revealed until the very end of the novel, so that the rumors of espionage and murder swirl around him go unchallenged and Gatsby starts to look very suspicious. Trimalchio’s Gatsby is also angrier and darker, which becomes clear in the climax of the novel when he argues with Tom Buchanan.

Daisy looks different in her earlier incarnation, too. Luhrmann told the Wall Street Journal that Trimalchio contained a much more complete picture of Daisy and Gatsby’s relationship, and he’s right. There’s a short but pivotal scene in The Great Gatsby in which Daisy and Tom attend one of Gatsby’s lavish weekend parties—in Trimalchio, that scene is extended: it becomes a rather hard-to-imagine peasant costume party, Daisy and Gatsby sneak off into the garden together, and it completely changed the way I read both novels.

It boils down to one moment at the party when Daisy tells Nick, “I’m going to leave Tom.” It’s the closest thing in either book to a real sense of dedication from Daisy. For once, Gatsby is not telling her what she would do—she is volunteering to leave, she wants to be with Gatsby, to give up her life with a man she no longer loves. But she admits that she hasn’t actually told Tom and that “I’m not going to do anything for a month or two. Then I’ll decide,” to which Nick replies, “I thought you’d decided.” Chilled by his response, I became distinctly aware in this early version of what Nick does not realize until the final chapter of The Great Gatsby: that “she had never, all along, intended doing anything at all.” I was left wondering throughout the rest of the novel if she even loved Gatsby at all.

The sense of tragedy that accompanies the end of The Great Gatsby feels hollow in Trimalchio. In fact, it feels like this unwinnable game from Slate (paddle against the current toward the green light until you are borne back into the past): clever, but so hopeless it lacks even the cathartic satisfaction of tragedy or the sense of hope and belief—however foolish—for which Gatsby is always remembered.

No longer grudgingly following a tenth grade reading list, I enjoyed both novels, and it was a thrilling experience to read them side by side. Trimalchio offers the fantastic and rare opportunity to witness an author’s progress: with the early version alongside the final one, I saw an evolution in Gatsby’s character from raw to refined, and an evolution in the story from nihilistic to tragic. I look forward to seeing a film that blends the two, making the American dream and the man who believed in it more complicated by drawing on the story Fitzgerald initially imagined.

Latest Comments

Have your say!