In his recent book, The Legitimacy Puzzle in Latin America, co-authored with John Booth, Mitchell Seligson dig through massive amounts of data to uncover the many dimensions of popular support for democracy in Latin America. Their findings mirror unfolding events in Honduras. Further, their analysis tells us that confrontational protests are an extension of the democratic process in Latin America, and that we should be careful in our regard of them.

In his recent book, The Legitimacy Puzzle in Latin America, co-authored with John Booth, Mitchell Seligson dig through massive amounts of data to uncover the many dimensions of popular support for democracy in Latin America. Their findings mirror unfolding events in Honduras. Further, their analysis tells us that confrontational protests are an extension of the democratic process in Latin America, and that we should be careful in our regard of them.

According to Dr. Seligson:

My sense is that what we are saying is that in our book, based on data from 2004, we already saw the difficulties that some countries, especially Honduras, might face because of their inability to establish their legitimacy. We of course could not possibly predict the specific event or the timing of the event. But, we do point to vulnerabilities.

From Chapter 8:

…theory strongly suggests that Guatemala and Honduras demonstrate greater risk for unrest, political turmoil, and support for antidemocratic regimes than do the other countries based on this indicator.

The eight countries in our study vary in other ways as well, perhaps the most important differences being their regimes’ abilities to ‘‘deliver the goods’’ to their populations. Once again, Costa Rica is the standout, with levels of social welfare, health, and education that are the envy of the region. Panama, too, has achieved impressive levels of welfare. At the other extreme are Guatemala and Honduras, whose governments have invested little in their own human capital and, not surprisingly, have populations with woeful basic indicators of infant mortality and literacy. Mexico is the industrial giant of the region, with ever-increasing trade ties with the United States. Capital flight, civil wars, and policy instability have kept Nicaragua’s performance on providing for its citizens dismal, despite the revolution’s efforts to advance education, basic services, and welfare. In short, our research design incorporates countries with many basic similarities of history and culture, yet with great divergence in experience with and levels of democracy. We expected, then, to find varying levels of legitimacy among these countries and that the consequences of low levels of legitimacy should matter….

Contrary to common expectations, high regime principles and regime institutions legitimacy values associate strongly with greater approval of some forms of negative political capital, especially support for confrontational tactics (including various forms of civil disobedience). Further, support for local government has a modestly positive association with support for rebellion and approval of confrontational political tactics. In contrast, the most influential dimension of legitimacy in predicting negative political capital is perception of the existence of a national political community. The stronger that norm is, the lower is the support for several forms of negative political capital. A similar pattern also was found for support for political actors and evaluation of regime economic performance.

Contrary to common expectations, high regime principles and regime institutions legitimacy values associate strongly with greater approval of some forms of negative political capital, especially support for confrontational tactics (including various forms of civil disobedience). Further, support for local government has a modestly positive association with support for rebellion and approval of confrontational political tactics. In contrast, the most influential dimension of legitimacy in predicting negative political capital is perception of the existence of a national political community. The stronger that norm is, the lower is the support for several forms of negative political capital. A similar pattern also was found for support for political actors and evaluation of regime economic performance.

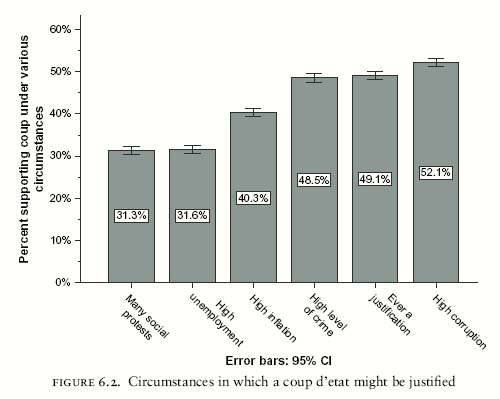

Taken together, these findings paint a complex picture of legitimacy’s effects on negative political capital. Those who perceive a national community and approve of incumbent actors and economic performance tend to have less negative political capital, a finding that corroborates the received wisdom on legitimacy’s effects. Diverging from our expectations, however, some legitimacy dimensions produce effectively the opposite outcome. Institutional support, regime principles legitimacy, and supportfor local government associate with approval of confrontational political methods. Clearly, Latin American supporters of democratic regime principles and of their (however imperfect) democratic national political systems and local governments nevertheless feel comfortable with protest. Thus, no one should assume that Latin America’s democrats and institutional loyalists will be politically passive or will embrace and employ only within-channels political means. Confrontation – protesting, occupying buildings, and blocking streets – makes up part of the culturally acceptable political toolkit of citizens of Latin American democracies. The implications of this finding are great: Policy makers, scholars, and the media would err seriously by imputing the protest or protesters in Latin America for any necessary repudiation of democracy or democratic institutions. Further, it would be just as incorrect to assume that rising support for democracy necessarily would reduce protest.

…triply dissatisfied citizens in Honduras (12 percent) and Guatemala (15 percent) is nearly double to over seven times greater than the percentage of the triply dissatisfieds in the six other countries. Once again, this application of our theory strongly suggests that Guatemala and Honduras demonstrate greater risk for unrest, political turmoil, and support for antidemocratic regimes than do the other countries based on this indicator.

Latest Comments

Have your say!