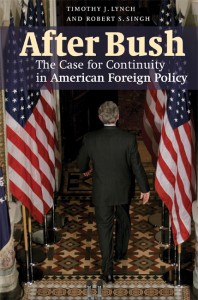

Writing for Commentary, Joshua Muravchik reviewed Tim Lynch and Rob Singh’s After Bush in this month’s issue.

After Bush: The Case for Continuity in American Foreign Policy

GEORGE W. BUSH has been one of the most reviled of recent Presidents, and he has poll ratings to match. But with the “surge” in Iraq giving signs of having snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, a number of observers have begun to argue that he will be rated more kindly in hindsight than he has been in real time. “There’s more ferment about the Bush legacy than is sometimes acknowledged,” concluded a recent summary in the Washington Post.

GEORGE W. BUSH has been one of the most reviled of recent Presidents, and he has poll ratings to match. But with the “surge” in Iraq giving signs of having snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, a number of observers have begun to argue that he will be rated more kindly in hindsight than he has been in real time. “There’s more ferment about the Bush legacy than is sometimes acknowledged,” concluded a recent summary in the Washington Post.

Now a book-length presentation of this point has arrived from, of all sources, the groves of British academe, where Bush is hardly more popular than, say, global warming. Timothy J. Lynch and Robert S. Singh, both of whom teach at the University of London, couch their defense of Bush in the form of a meditation on what will follow after his administration. Their surprising conclusion: “None of the key elements of the Bush Doctrine . . . will be abandoned in practice by successor administrations, whatever their rhetorical recalibrations and tactical adjustments.”

Why not? Because, Lynch and Singh answer, Bush’s analysis of the challenge we face from Islamic terrorists was basically correct. Like it or not, a “second cold war,” no more of our choosing than the first one, has been thrust upon us. The authors prefer the term “second cold war” to “World War IV”—favored by Norman Podhoretz, R. James Woolsey, and others—because it emphasizes the ideological dimension that, in their judgment, was more in the forefront of our contest with Soviet Communism than it was in World Wars I and II. And much like its predecessor, they write, this second cold war is destined to last for a long time: “Defeating jihadist Islam ultimately requires nothing less than the reform of Islam to separate mosque and state, modernization of Arab and Muslim societies, and steps toward genuine self-government.”

Hence, there is discomfiting news for all those looking forward to January 2009 as the end of the Bush years. That date, observe Lynch and Singh, “marks only the end of the beginning of an epochal struggle.” What is more, they believe they can discern, through the din of reproach directed at Bush, the strains of an incipient national consensus on the matter. This emergent consensus is based on a confluence of factors: the undeniable severity of the threat; the continuance of America’s global primacy; the “appeal of a distinctly American internationalism”; bipartisan support for the war on terror even if not the Iraq war; and the “vitality of American exceptionalism,” in which “values as well as interests have been, and will remain, crucial

components of American policies.”

IN SHORT, not only will the conflict endure but so will Bush’s approach to it. For one thing, “there is nothing viable with which to replace it.” For another, it is “working.” In saying this, Lynch and Singh are not referring to the situation in Iraq, since their book was written when our fortunes there were still at a low ebb. Instead, they have in mind the relative dearth of terror attacks against the West and the initially encouraging impact of Bush’s democratization policies on the Muslim Middle East.

But even concerning Iraq, Lynch and Singh insist that the war was “not misconceived” but rather “seriously mismanaged.” They cite such apparent mistakes as our deploying too few troops and disbanding the Iraqi army, and they offer an especially biting judgment of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who, in “abandoning the Powell doctrine of overwhelming force, . . . committed an error of cardinal magnitude.” But they also rebut a range of other criticisms of Bush’s policies in Iraq.

Wryly, Lynch and Singh mock European leftists who, “rather than organize to meet a realized and growing danger [i.e., terrorism], obsess about a predicted one [i.e., global warming]”—and who march in absurd protest against America for the sin of overthrowing a “fascist dictatorship.” They also skewer the anti-Bush (and anti-Israel) polemicists Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer:

‘Two of the world’s most respected realist scholars have determined to condemn the war on terror on the basis of its foreign reception. Rather than unpopularity being an unfortunate byproduct of the pursuit of the national interest, it is now, by definition it appears, a negation of the national interest. . . . For liberals to pore over polling data to find empirical evidence of the unpopularity of the war on terror is not unusual. For realists to join them is a denial of the theoretical clarity of realism itself.’

As for the warnings of the so-called realists that American “unilateralism” will cause others to band together against us, Lynch and Singh point out that no such coalescence has occurred, for the simple reason that the impediments to it are too great and likely to remain so.

ALL OF this is delivered in the matter-of-fact tone that is more characteristic of British discourse than our own, and without any trace of selfconsciousness or defensive handwringing. The thesis is one with which I feel great sympathy, although here and there I would have wished for greater precision or deeper explication.

Lynch and Singh assert, for instance, that there is no alternative to Bush’s policies because those policies are working. But this is something of a non-sequitur. The world does not lack for examples of wise or prudent ideas replaced or defeated by foolish or unworkable ones. More important, the assertion that Bush’s policies are indeed working could use sturdier proofs than Lynch and Singh provide. In the absence of such proofs, it might have been wiser to advance a more modest claim—namely, that no substantive alternatives to Bush’s main policies have in fact been proposed, which is reason enough to give them time to demonstrate their efficacy.

A second contention needing development is the authors’ assertion that success in our struggle requires the “reform of Islam.” This cries out for a digression. When, if ever, has Islam been reformed in the past, and by what means and in what space of time? In the same breath, Lynch and Singh cite the need for “steps toward genuine self-government” (emphasis added). This would seem to imply that political change may be an even more distant goal than religious change. I would have thought the reverse. Either way, though, one wants to hear more.

Finally, even if Lynch and Singh are right that Bush’s successor, whether Republican or Democrat, will find himself compelled to prosecute the second cold war along the lines set by Bush, how reassuring is that to those of us who believe in these policies? As President, Jimmy Carter found that, despite his longing to lead America away from the “inordinate fear of Communism,”he could not unilaterally end the cold war, yet he waged it so halfheartedly and incompetently that we were in the process of losing until the American people replaced Carter with Ronald Reagan. This latest cold war has been visited upon us by an enemy who has already demonstrated his deadliness. If we fail to prosecute it with the utmost vigor and seriousness of purpose, we will be inviting disaster.

Still, these are relatively small complaints. To critics and decriers of the Bush doctrine, two wellversed scholars have forcefully posed the question: if not this, then what? In doing so, they have provided a most welcome tonic to the shrill election-year demagogy that has filled the American air.

Latest Comments

Have your say!